The Impact of Falling Oil Prices

Is Latin America Part of Global Oil Supply Adjustment?

International oil prices have declined by 40% recently. Some of the region’s oil producers have been better than others at adjusting to this reality. In more market-oriented countries like Colombia and Mexico, the collapse of oil prices has not translated into a full-blown crisis thanks to the flexibility of their policy frameworks. In these countries, their floating foreign exchange rate regimes are doing the work of helping their economies deal with the external and fiscal adjustment that such collapse in oil prices entails. But in those countries like Venezuela that are unable or unwilling to adjust, the oil price collapse is significantly deteriorating their dollar liquidity situation and leading to a serious macroeconomic crisis.

Most analysts first evaluate the oil price shock at the macroeconomic level; however, at the industry level, national oil companies also are under financial stress. As a result, their capital investment plans are being slashed. The growth prospects of the countries where they operate are then negatively affected as the national oil companies are generally the largest single company in the country. And this creates a negative loop since the oil production outlook of the region also faces uncertainty and pressure because investment is the only way to guarantee future production. As a result, the macroeconomic impact of the decline in oil prices gets magnified.

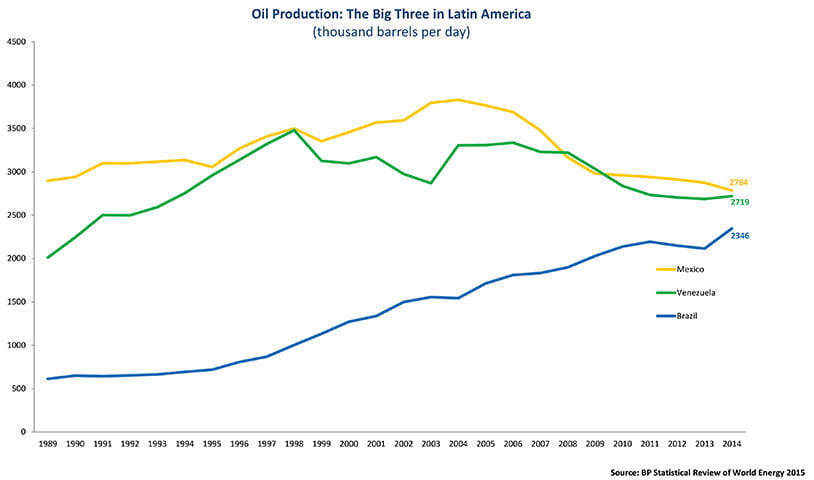

Oil production is already being affected in Mexico and Venezuela; Colombia also confronts downside risks. While Brazil had become the region’s second most important producer surpassing Mexico last year, recently it massively revised its very aggressive oil production goals: the national oil company Petrobras now only expects a 700,000 barrels a day increase in five years, a sharp drop from the three million barrels a day increase it had previously forecast for 2020,

However unwilling, Latin America is becoming part of the global oil supply adjustment despite its very attractive oil and gas resources yet to be developed.

A big question is which oil industry in which country will be able to come out of this oil price shock in better shape. Mexico’s shallow and deepwater resources, Venezuela’s extra heavy Orinoco belt, Brazil’s highly productive offshore presalt play, and the vast shale gas and oil resources of Argentina’s Vaca Muerta are all contenders.

MEXICO: LIGHT AT THE END OF THE TUNNEL

The first casualty of the oil price adjustment was Mexico. The country had already experienced a decline in production of close to 100,000 barrels per day last year and has so far this year been hit with a further decline of more than 200,000 barrels per day in the January-April 15 period compared to the same period last year, mostly because of the sharp pace of decline in Cantarell, Mexico’s second largest field. A decade ago, it produced two million barrels per day, but has only averaged 250,000 barrels a day in the first half of 2015.

While Mexico is an oil-exporting country, the country feels the oil price decline not through its external accounts, but through its fiscal accounts. Last year, oil income continued to represent about 30% of the government’s total revenues. At the same time, Mexico’s oil exports are only 9% of total exports, with oil and gas holding equal shares of total imports. As a result, Mexico’s energy trade balance is already negative given its increasing dependence on U.S. natural gas and gasoline imports for its own consumption. In fact, this dependence will only increase in time given Mexico’s aggressive plans to expand its pipeline infrastructure and the government has plans to quadruple Mexico’s natural gas import capacity from the United States by 2018.

For countries such as Venezuela and Ecuador, such an increase in energy imports would be catastrophic, in part because of large energy subsidies. But Mexico no longer subsidizes energy prices. In fact, current gasoline prices in Mexico are above international prices. This price differential is effectively a tax on gasoline consumption, allowing the government to compensate somewhat for this year’s decline in oil fiscal revenues from exports. Between January and April, gasoline taxes provided the government with an additional $5 billion in revenues. That meant that instead of falling by 50% in dollar terms, government oil revenues, which now include gasoline taxes, fell by only 30% in the first four months of the year compared to the same period last year.

Despite declining oil production, Mexico’s oil future is looking bright thus far because of a landmark energy reform passed last year that opened the oil and gas sector to private capital after eighty years of absolute government control. The government is proceeding with its auctions of oil blocks this year and has so far announced tenders for about 50 blocks, with the first auction for 14 shallow water contracts slated to take place on July 15, followed by an additional five contracts in September and 26 onshore marginal fields in December. Still expected to come are oil tenders for deepwater, heavy oil and unconventional resources. Overall, Mexico plans to auction a total of 914 fields in the 2015-2019 period and that will allow Mexico to project oil production increases in the medium term, despite current declines in output.

VENEZUELA; NO EASY WAY OUT

No country in the region is suffering the collapse in oil prices more than Venezuela, where oil represents 96% of total exports and more than 50% of fiscal revenues. The magnitude of the impact has significantly increased the risks that the national oil company PDVSA and the government will not be able to service their debt obligations.

While Venezuela is sitting on the largest oil reserves in the Western Hemisphere, increasing oil production as a way out of the country’s severe economic and financial crisis does not seem to be an easy option. The oil industry does not operate in a vacuum and is not immune to the economic collapse in the country with an inflation rate that is the highest in the world (already at triple digits), widespread scarcity and a growth rate estimated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) at -7% this year compared to last.

To cope with the situation, the government has significantly reduced imports—effectively starving the private sector of much needed dollars to continue operations. PDVSA seems to have stabilized production, after a decline of more than 100,000 barrels a day last year, and the government is believed to have raised about $10 billion in financing this year, if Chinese financing is included. Venezuela also seems to have reduced its subsidized sales of oil to Caribbean nations with preferential payments through the Petrocaribe oil alliance.

The reduction of subsidized oil exports and the raising of financing have not been sufficient to improve the country’s dollar liquidity situation: international reserves have declined by almost $6 billion and by July 2015 were already below $16 billion, their lowest level since 2002. And this dollar liquidity situation is a concern because debt service to both the Chinese and bond debt investors is in the order of $15-20 billion annually.

It will be very difficult for the Venezuelan oil industry to operate successfully under such financial and economic conditions. But addressing them requires major changes to the current economic model, and this includes energy policy. In the absence of reform, oil production faces the risks of further declines. Venezuela seems to be becoming a more costly oil producer and PDVSA’s cash flow situation remains under duress with arrears to its oil service providers in the order of $20 billion.

The capacity and willingness to carry out such a major change in economic and energy policy seem difficult today without political change. Any effort at policy adjustment has been aborted. A devaluation of the official exchange rate was needed to ease PDVSA’s—and the government’s—fiscal situation, along with a major adjustment of gasoline prices. At four cents per gallon, gasoline prices in Venezuela are the lowest in the world and do not even cover the cost of production, let alone the cost of importing the 100-200 thousand barrels per day in oil products that the country is having to import today.

But nothing has happened. In the meantime, Venezuela’s production of conventional crude seems to be experiencing declining rates of more than 5%. The national oil company PDVSA seems to believe that the only way to compensate for this is by bringing heavy oil on stream from its vast Orinoco belt reserves. It currently has six different joint ventures to do so with Chinese, Russian and international oil companies like Chevron and Repsol.

Still, as every new barrel of oil coming from Orinoco is significantly heavier, and given the limited capacity to upgrade this crude, it requires mixing it with light oil or diluents which Venezuela needs to import given declines in own light crude. This increases the marginal cost of oil production, making the economics of a 30% royalty—one of the highest on the planet—too costly in this price environment.

BRAZIL; WHEN IT RAINS, IT POURS

Brazil became Latin America’s second-largest producer late last year, overtaking Mexico. But it is not necessarily oil prices that are clouding Brazil’s oil outlook. Rather the national oil company Petrobras is bogged down in a severe corruption scandal that has left the company highly indebted, provoking major revisions in its 5-year capital investment plan (see the other articles in this issue on Petrobras by Simon Romero and Lisa Viscidi.)

All of Brazil’s anticipated growth will come from its pre-salt fields. Pre-salt refers to the oil reservoirs found under the thick layer of salt in Brazil’s deepwater. These fields have proved to be highly productive, with production already at more than 700,000 barrels a day in May—expected to represent more than 50% of total oil production by 2020. Petrobras believes that presalt is still competitive at a $45-55 per barrel range.

Even if Brazil will see oil production increases, this internal crisis is having important consequences for economic growth as the oil industry represents about 13% of GDP. The corruption scandal is also significantly impacting Petrobras’ local supply chain, including the most important construction companies in the country.

At the heart of this institutional crisis was a very aggressive industrial policy of local content requirement gone wrong. What this policy did was force Petrobras to spend more than 70% of its $40 billion annual capital expenditures—an amount which was already one of the highest in the industry—in the domestic economy to develop an oil service sector. It had to do this while at the same time subsidizing gasoline imports, as well as shouldering the very costly development of its offshore oil resources. And all of this without much help from any other company as legislative changes forced Petrobras to hold a 30% stake in any presalt development and be the sole operator.

Petrobras and the government are now having to pick up the pieces of its misguided policies in the midst of a very difficult macroeconomic adjustment which has already thrown the country into recession, taking with it President Dilma Roussef’s popularity, now below 10%.

The only way out for Brazil’s oil industry—and for Petrobras—is a major overhaul of the same energy policies that led to this crisis. This means a major revision of its pricing policy, local content requirement policy and presalt legislation (a bill to that effect is already in Congress).

ARGENTINA: COUNTER-CYCLICAL ENERGY POLICY

When the world oil price was more than $100 a barrel, government regulation did not allow Argentine oil companies to earn more than $50 a barrel. Now that oil prices have collapsed, Buenos Aires is going much higher than international oil prices by allowing its producers to realize $77 a barrel for their oil—much higher than international oil prices and even providing an additional subsidy of $3 a barrel, which means an average of $80 a barrel for Medanito light oil. Go figure.

But Argentina is defying the global energy trend in more than one aspect: its national oil company YPF announced that its 2015 $6 billion capital expenditure was unchanged from last year, continuing relentlessly in its quest to increase production (YPF’s oil and gas output in the January-April period increased by 6% and 15% respectively in relation to the same period last year). YPF produces 40% of the oil output and about 30% of Argentina’s 116 million cubic feet a day of gas production. And the rig count—which is a forward-looking indicator of oil production—is increasing in defiance of the worldwide trend.

Because Argentina is a net energy importer, the decline in oil and gas prices is actually helping Argentina’s energy trade deficit, which fell by almost 50% in January-May in relation to the same period last year. This likely means that the annual $6.5 billion energy deficit in 2014 is likely to be cut in half, as terms-of–trade effects and lower volumes due to the sluggish economy help to significantly cut its $10 billion a year bill in energy imports to maybe $5 billion— contingent on normal winter weather.

However, some questions remain about a larger development of Argentina’s vast shale resources, a possibly important source of growth for the country’s economy in coming years.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration identified the nation as holding the world’s second largest shale gas and fourth largest shale oil reserves. This translates to an estimated 802 trillion cubic feet of technically recoverable shale gas and 27 billion barrels of oil.

In April 2015 YPF, the largest shale operator in the country, reported that shale oil production remained very low at 22,900 barrels per day and 67 million cubic feet per day of natural gas from three joint ventures in Vaca Muerta: one with Chevron at the Loma Campana field, a second one with Dow Chemical at the El Orejano field, and a third joint venture with Petronas at La Amarga Chica field. Vaca Muerta has been compared to ExxonMobil’s Eagle Ford shale field in Texas in terms of its oil and gas potential, but it is even larger in size.

In the meantime, YPF continues with its relentless drive to emulate U.S. shale producers by reducing the costs of extracting shale oil and gas in Argentina. But despite a pro-business legal environment, the development of Vaca Muerta will not be contingent only on a better price outlook and continuation of cost reduction. It will be particularly dependent on the expected change in the governmental macro policy framework that could come after the October 2015 presidential elections. Necessary changes include the elimination of capital and import controls, moving to a floating exchange rate and the elimination of energy price controls.

U.S.-LATIN AMERICA ENERGY RELATIONSHIP

Equally important to understanding the impact of the oil price collapse on the Latin American oil producers is to understand why it has occurred. This supply shock was mostly generated by the U.S. shale revolution, which has been responsible for the oil oversupply in global oil markets. And this fact brings additional pressure to bear on the competitiveness of Latin American oil industries, which are neither the low-cost oil producers found in the Middle East, nor the competitive fiscal and legal regimes found in the United States.

U.S. shale oil and gas producers managed to bring more than one million barrels per day of oil into the market last year, while at the same time reducing cost and improving efficiencies at $100 a barrel. This process has accelerated even more this year, allowing a part of the U.S. shale oil and gas industry to be competitive even at these low prices. This will put even more pressure on the oil industries in Latin America.

The region’s oil trade balance with the United States is still positive, but it has fallen to about 700,000 barrels per day from almost 4 million barrels per day a decade ago. The United States is not exporting its shale oil to Latin America directly, but U.S. oil is finding its way to the region through the surge in oil-refined products. And this is what is leveling the oil relationship between the United States and the region.

So which Latin American countries and oil industries can weather the challenges ahead? Mexico seems to be a good bet because, enjoying a solid macroeconomic framework, it has already done the homework of liberalizing its oil and gas sector, equating its pricing policy to international levels, linking its energy sector to that of the United States.

And while the potential is great in Venezuela, Brazil and Argentina, questions about their oil sectors will remain as they struggle either with uncompetitive energy policies, or with an inadequate macroeconomic framework or with both.

Fall 2015, Volume XV, Number 1

Luisa Palacios is the head of Latin America macro and energy research at Medley Global Advisers in New York and a researcher for the Center on Energy and the Environment at the Business School (IESA) in Caracas, Venezuela.

Related Articles

Oil and Indigenous Communities

On a drizzly morning in late February, a boat full of silent Kukama men motored slowly into the flooded forest off the Marañón River in northern Peru. Cutting the…

Mexico’s Energy Reform

The small, white-washed classroom at the University in Minatitlán, Veracruz, was packed with a couple dozen people who, although neighbors, had never met…

Geothermal Energy in Central America

When we think about global technology leaders, Central America does not typically come to mind. But Central American countries have indeed been in the…