The Many Meanings of Yerba Mate

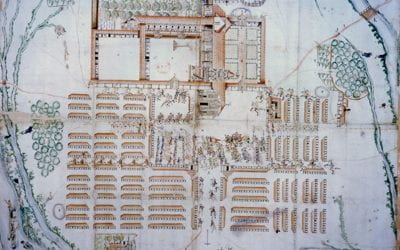

Across Borders, Sharing a Guarani Drink

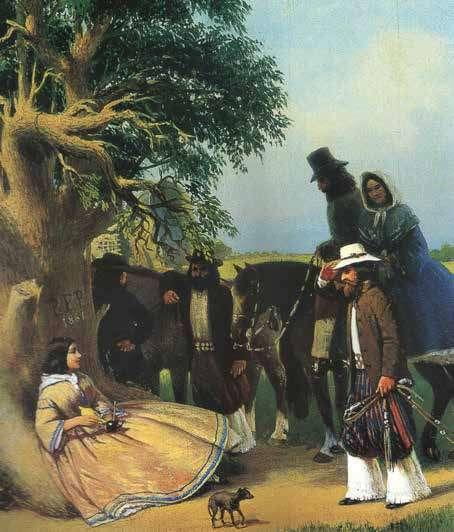

Un alto en el campo by Prilidiano Pueyrredón represents a typical Pampas scene, the tree, the gauchos and the mate. Image by Prilidiano Pueyrredón.

I first encountered yerba mate as a Peace Corps volunteer in rural Paraguay. Everywhere I went, and at all times of the day, I saw small groups of people passing around a hollowed out cow’s horn or gourd (guampa) filled with ground leaves and a single metal straw sticking out of the top. I had never thought of drinking from a cow’s horn or gourd. Drinking out of the same metal straw (bombilla) was even more jarring. Wasn’t anyone worried about germs? When I tried to refuse an offer of yerba mate from my neighbor because I had a cold, she responded that she had added some herbs especially for colds and so I had even more reason to share the mate with her. She wasn’t at all concerned about catching a cold from me!

Drinking yerba mate is a communal activity. One person in the group (the server) pours some hot water (or cold water for tereré) into the guampa and passes it to a companion who dutifully sucks all of the liquid from the shared straw and returns the guampa. The server then refills the guampa with water and passes it to another person in the group. Conversation flows as the process repeats itself until the yerba mate loses its flavor—about thirty minutes. Peace Corps training taught me the cultural importance of mate; most Paraguayans cannot imagine anyone not drinking it—and I quickly learned that sharing mate was a great way to make friends and gain acceptance. Yerba mate’s stimulating properties intensified my appreciation for the drink and soon I was consuming large quantities throughout the day…until I could no longer tolerate my mind racing every night for hours after everyone else had fallen asleep and I learned moderation.

Until recently, yerba mate was an exotic substance brought to the United States either by tourists returning from the Southern Cone or nostalgic expatriates wanting to maintain an important cultural practice from their homeland. Health food stores were the first to promote yerba mate and, as interest spread, enterprising websites materialized touting a long list of vitamins, minerals, antioxidants and general health benefits associated with the plant. Companies like Guayakí (founded in San Luis Obispo, California, in 1996) began marketing yerba mate as a healthier alternative to coffee and tea. Now yerba mate tea bags and iced mate are sold in national chains like Safeway, Walgreens, and Walmart and Guayakí is installing automated brewing systems in university cafeterias to expand its appeal to young people. Yerba mate has also entered the trendy energy drink market. Such campaigns have largely been successful. In 2014, Guayakí reached $27 million in sales—primarily to United States consumers—and the amount is growing at over 26% per year.

Yerba mate has long been integral to the identity of Paraguay, Uruguay, Argentina and southern Brazil where it is ubiquitous. Walls of different yerba mate brands fill grocery store aisles and the telltale paraphernalia are found in homes, workplaces, schools, parks and automobiles—everywhere a group might convene. Yerba mate is different from other stimulants like coffee and tea because of the deep cultural meaning associated with the special manner in which it is drunk. Individuals staying up late for work might drink mate by themselves, but generally it is a communal, not a solitary, pastime.

As part of a grant from the Institute for Humanities Research at Arizona State University (ASU), I recently gathered a group of Argentines, Paraguayans, a Brazilian, an Uruguayan and a U.S.-born scholar of Latin American studies to discuss the cultural significance of yerba mate. All of the participants agreed that drinking yerba mate is much more than getting a caffeine fix; it is a cherished opportunity to relax and converse with friends, family, co-workers, or even strangers. As Milagros Zingoni originally from Nequen, Argentina described, “I wake up with this [yerba mate] and when I return from work at 5 or 6 my husband and I drink this again. We usually have dinner at 8 and by 11 I am drinking this again.” Whenever someone visits, yerba mate is prepared and conversation ensues. Mate is not only about friendship and conversation; it is also a way to build connections with strangers. It is an open invitation to engage with someone new.

The author as Peace Corps volunteer, 1998-2000 in Curuguaty, Paraguay, sharing a yerba mate with friends. Photo courtesy of Julia Sarreal.

According to David William Foster, an ASU professor who has been studying Argentina for more than half a century, “One of the singular characteristics of Argentine culture is this omnipresence of the mate…No matter how high you go on the social scale, no matter how high you go on the intelligentsia scale, everybody is drinking mate, this indigenous drink.” Despite its cultural importance, not everyone in the Southern Cone is a fan. Foster noted that Jorge Luis Borges, who couldn’t have been more Argentine, didn’t drink yerba mate.

One of the most important aspects highlighted by the participants in the panel was that yerba mate is socially inclusive. It transcends almost every barrier—social, racial, economic, gender, and sexual orientation. Milagros gave the example of how when she was a child and HIV was becoming a big issue, a couple of doctors purposefully shared their mate with HIV patients in order to encourage Argentines not to be so afraid of people with HIV. Drinking mate can also more informally bring people together and build a sense of community among those who would not otherwise interact in such an intimate manner. Enrique Yegros (Paraguayan) recounted how every day when he walked to school as a child, the security guard would be drinking yerba mate and would share it with him. In fact, anyone that Enrique passed on the street would share yerba mate if he asked. But of course, not everyone feels comfortable asking for mate from a stranger.

All of the participants concurred that yerba mate pervaded their lives in South America, but many did not realize its importance until they moved to the United States. Diego Vera, a Paraguayan, commented that he had never given yerba mate much thought until recently. When he was back in Asunción doing some paperwork with his American wife, she pointed out that in every single government office someone was drinking it or had it on a desk. As Diego explained, “[yerba mate] is such an intrinsic part of us that you really don’t think about it until somebody else points it out.” Thinking back, Diego says that he can’t imagine his childhood and many conversations or scenarios with his mother and grandmother without yerba mate. Enrique summarized, “[Drinking yerba mate] is part of the culture, you are born with it.”

“Mate jardín” (Mate Garden) by Facundo de Zuviría, 2010. The gourd container for the dried leaves prepared for the infusion of hot water, the metal “bombilla” to suck the tea-like drink, and a bouquet of fresh leaves of yerba mate (ile paraguariensis). Photo by Facundo de Zuviría, www.facundodezuviria.com

Even while Paraguayans, Uruguayans, Argentines, and southern Brazilians share an enthusiasm for yerba mate, they also embrace regional differences. Brazilian yerba mate is greener and more finely ground. Even though it is drunk only in the southern part of the country, regional differences still exist. João Pessato was born in Rio Grande do Sul, where his family drank yerba mate with hot water but when his family moved north to the warmer state of Mato Grosso do Sul, they changed to drinking it with cold water. Paraguayans also drink yerba mate with both hot and cold water but most Argentines and Uruguayans would never think of using cold water. Paraguayans also differ in their practice of adding yuyos (herbs) to the water. These yuyos can be either medicinal or refreshing. Diego described how as a child, his family would send him to the yuyera (the woman who sold yuyos) in the market. Based on how you felt or what you dreamed, the yuyera chose specific yuyos from her supply and prepared them in front of you with a mortar and pestle. Many Paraguayans grow yuyos in their own yard or garden. The idea of flavoring the yerba mate has been catching on. Many companies now sell packaged yerba mate with citrus, mint, or herbs and some are adding more experimental flavors such as guaraná and coffee. Companies also market an extensive variety of yerba mate styles to appeal to every taste (for example: low powder, with stems, without stems, smooth, intense, aged). But there is little cross-over among countries. Supermarkets in each country sell national brands of yerba mate, and during the panel at ASU, all of the participants patriotically claimed their country’s yerba mate as the best.

Such beliefs derive in part from yerba mate’s incorporation into each country’s national identity. The gaucho—adopted by Argentines, Uruguayans and southern Brazilians as emblematic of their country’s rural past—is remembered as an avid yerba mate consumer. National memories of yerba mate are not limited to the rural areas. Belle Époque-era immigrants to both the city and the countryside quickly adopted yerba mate as a way to assimilate. In Paraguay, national identity is linked to tereré, and many attribute its popularization to soldiers fighting in the Chaco War (1932-1935).

Connections with national identity have the tendency to obscure other meanings and origins. Argentine Gustavo Fischman commented during the ASU panel that yerba mate has been nationalized, and as a result, “very few people will make the direct connection that we are drinking something that has indigenous roots.” Most of the panelists agreed. The Paraguayans recognized that Guarani artisans make and sell yerba mate paraphernalia, but otherwise admitted that little is known about the drink’s Guarani origins.

Like most caffeinated substances, Europeans initially found yerba mate repulsive: a green bitter drink consumed by Indians! It was unlike anything most Europeans had ever drunk. Other caffeinated drinks like coffee and tea would take another couple of centuries to become popular in Europe. Moreover, Spaniards were not initially looking for new and foreign substances to introduce back home. The conquistadors were much more interested in finding mineral wealth and saving souls, and as Rebecca Earle points out in The Body of the Conquistador: Food, Race and the Colonial Experience in Spanish America, 1492-1700, Spanish settlers were much more interested in replicating their old-world Spanish diet in the Americas than they were in bringing foreign foodstuffs and strange substances back to Europe. Still, the use of yerba mate spread fairly rapidly among European settlers to South America.

Yerba mate’s growing popularity in the colonial period created some controversies. European settlers and travelers to the region wrote extensively about the drink’s many supposed attributes. On one hand, it was reputed to give strength, rejuvenate, and clarify the senses and was often described like a wonder drug that could cure a variety of maladies. On the other hand, too much yerba mate was described as a vice that was addictive and made people lazy and willing to do anything to get it. Most authors conceded that yerba mate was a good thing when used with moderation.

By the 18th century, most people in the Río de la Plata region consumed yerba mate regardless of racial or economic background. From elites to novitiates in Jesuit colleges to slaves and Indians, most everyone drank it daily and reputedly valued it as much as, if not more than, any basic foodstuff. Day laborers were known to refuse to work if they didn’t receive their expected ration of yerba mate. The reach of the drink extended to Peru, Bolivia and Chile and almost everyone writing about the Río de la Plata region mentioned it. They frequently compared it with chocolate, coffee and tea—all foreign drinks introduced to Europe. Its resemblance to tea was especially emphasized.

Despite yerba mate’s widespread use in South America, its popularity did not spread outside of the region until recently. As an alternative tea or energy drink, yerba mate is adopting different cultural practices in the United States, Europe, and Asia. But still, the unique communal form of drinking—along with all of the connotations associated with friendship and the building of social connections—remain strong in South America.

Spring 2015, Volume XIV, Number 3

Julia Sarreal is an Assistant Professor at Arizona State University. She received a Ph.D. in Latin American History from Harvard University in 2009 and is the author of The Guaraní and Their Missions: A Socioeconomic History (Stanford University Press, 2014).

Related Articles

Jesuit Reflections on their Overseas Missions

When you think of Jesuits in their missions around the world, you—the casual reader—might not think of Plato or ancient Greek authors. Yet two of these…

Paraguay: Un país en una lengua misteriosa y singular

English + Español

If you arrived in a country where almost 90% of the inhabitants speak Guarani, an official and national language along with Spanish but do not identify themselves as “Indian” or aboriginal…

Territory Guarani: Editor’s Letter

DRCLAS receptions are bustling affairs, sparkling with ample liquor, Latin American tidbits and compelling conversations. It was at one of these receptions that Jorge Silvetti and Graciela Silvestri first approached me casually regarding an issue about the Guarani…