The Maya Hand Down a Recipe for Chocolate

From Cacao to Tiste

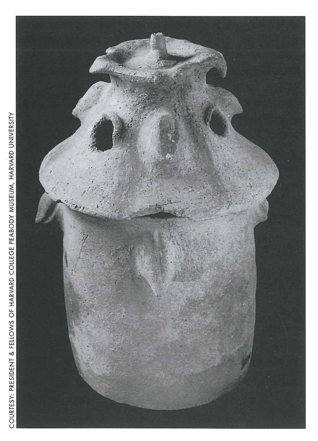

Inside the Harvard Peabody Museum Annex, rows and rows of metal shelving reveal hundreds of clay pots and shards, all catalogued with numbers on their sides. Most of these are decorative, with red and black glaze, and intricate designs. One plain pot easily overlooked has just a remnant of color. This is pot C597, barrel-shaped, measuring about 20 cm high with its lid. Only the pod-like appendages, at the top of the base and on the lid, hint at its loftier purpose.

Called a “cacao pot” or a “lidded incensario” by museum staff, this particular pot was found by Harvard archeologists in 1895 at the Maya site in Copán, Honduras, at the base of a stone monument to the 15th ruler in the Copán dynasty. Barbara Fash, a Research Associate at the Peabody Museum, places this pot around 700 BC. The appendages represent cacao pods she says, which indicate the pot held cacao, in some form. The fact that this pot was taken from a sacred, revered site indicates that it, and whatever was inside, was used in ritual.

Anthropologist Sophie Coe, writing in her book America?s First Cuisines, distinguishes between cacao “the tree and its products before processing,” cocoa “the product after processing had begun,” and chocolate the term we all use now, what Europeans called the drink when they brought it back from the Americas.

The Maya living along the Pacific Coast of Mesoamerica — perhaps as early as 3000 BC — first domesticated the cacao trees, cultivating the wild varieties easily in the humid climate. “It’s an interesting tree,” says Fash, “because it’s of a variety that doesn’t grow in our climate, so it’s odd to see it at first. Sometimes they [the pods] hang off branches, but other times right off the trunk of the tree.”

She describes the pods as being palm-sized and yellow or reddish in color. When you open it, Fash continues, “there’s a white, fleshy, sort of bed for the seeds in the pod.” Cocoa is produced from the seeds, or beans, as they are sometimes called.

In Cuisines, Coe supplies the following guidelines to preparing the seeds, adding this caveat: “It is no easy thing to transform the beans, wrapped in their white flesh inside the pod, into something that tastes and smells like chocolate. The first step is to gather the ripe pods and allow them to ferment for a few days…. After this, the seeds are removed…and allowed to dry; then they are carefully toasted and peeled. The peeled nut is ground, and reground, and reground again…preferably heated by a small fire or a pan of hot coals under it.” The powder is made into a drink then, or “formed into small storable cakes.” The drink was beaten, “to raise the foam, which was considered the best part of the drink and the sign of quality.”

Quality was a necessary attribute. “Used as a ritual drink,” says Fash, “the Maya were feeding their most precious substance to the gods.” It had to be good. This food also provided nourishment for the elite, who drank cocoa during ceremonies. To the basic powder derived from the seeds, other ingredients were added — mainly chile and cinnamon.

The cacao pots, such as the one found in the base of the monument in Copán, would have been made for such ceremonies. “They were produced quickly, for a special occasion,” says Fash. “Lots of these pots have been found, in similar settings.” In one case, Fash, notes, Hershey Foods Corporation was called upon to test the residue of several pots, which showed that they had contained some liquid form of cacao. Other pots were decorated with a hieroglyph which researchers believe represents the Maya word for “cacao” ka-ka-wa — indicating that they, too, played a role in the ritual use of cacao.

Fash believes that cacao took on its grand significance by the very process of domestication. “If you’re part of the process…of domestication, it’s time consuming and labor intensive, a religious commitment almost, because, like growing anything, you have to invest a lot of yourself into making it work.”

From this enormous effort, she says, a “culture of religion” grew, and like maize, the cacao seed became a sacred entity.

Fash says that today, descendants of the early Maya still offer cacao to the gods, leaving their gifts in caves. Mostly however, chocolate has become a common item, but retains much of its earlier flavor. Fash describes tiste — a chocolate drink she has had in Copán, Honduras, where Harvard’s cacao pot was crafted many centuries before. This is a powdered mixture of toasted cacao, toasted maize, sugar, cinnamon and achiote which provides a red color. This mixture is ground into a powder and then added to milk or water.

Mole, a Mexican chocolate sauce served over chicken, also contains chile and cinnamon, the ancient mainstays. “It’s so unlike the way we’re accustomed to being prepared, as far as chocolate goes,” Fash comments, listing the sweets we associate with a particular chocolate taste: chocolate cake, chocolate frosting, hot chocolate. “They almost always add something to it, which gives it a very different kind of flavor experience. You’re almost not sure you feel right afterwards!”

Spring/Summer 2001

Susie Seefelt Lesieutre was a publications intern at DRCLAS for the fall semester and is currently working with the Center’s publications director. She is enrolled in the Certificate for Publishing and Communications program at Harvard Extension. In 1990 she received a Master’s degree in TESL; she has taught ESL in the US and abroad.

Related Articles

Salvadoran Pupusas

There are different brands of tortilla flour to make the dough. MASECA, which can be found in most large supermarkets in the international section, is one of them but there are others. Follow…

Salpicón Nicaragüense

Nicaraguan salpicón is one of the defining dishes of present-day Nicaraguan cuisine and yet it is unlike anything else that goes by the name of salpicón. Rather, it is an entire menu revolving…

The Lonely Griller

As “a visitor whose days were numbered” in Buenos Aires, Argentina, he tossed aside dietary restrictions to experience the enormous variety of meat dishes, cuts of meat he hadn’t seen…