The Meanings of Samba

What has happened to the dance of racial democracy?

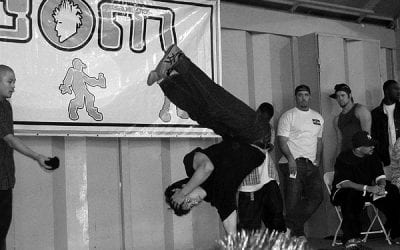

2006 Carnaval. Photo by Jason Gardner.

I like dancing, and no better dance than samba. My samba, though, always feels, as it no doubt looks, like a stilted attempt at the dance, rather than the real thing. I can recognize that in videoclips from Rio’s Sambadrome, in the street during the Carnivals of Olinda and Salvador, or when Brazilian friends dance in celebration of a World Cup victory. Real samba is a body unselfconsciously flowing in response to a syncopated beat, melding curious indolence and sexual charge, form and spontaneity. Arms extended, the feet seem to transmit a rhythm to be riffed by hips and belly and shoulders as the whole body swings, dips to the ground. Then stops for a nanosecond, only to fill again with movement the fleeting void left by the missed beat of the samba music. No single word—graceful, frantic or sexy—will do to describe the real thing, though samba is all those things. But stilted it can never be.

So if I can recognize and savor it, why can’t I samba? Well, some of the explanation may stay between my analyst and me. I need no help, though, to realize that I can’t samba because I don’t samba, except in my head, on any but rare carnival occasions. In a given year carnaval—not quite “carnival” in English— comes often for those Brazilian friends and the street dancers. The Sambadrome dancers hone their performances the year round in the ensaios (rehearsals) of their samba schools. The lesson: it’s only in practice that a body attuned like mine to regular 2/4 or 3/4 beats could begin to flow with the regular irregularities of samba music.

But would practice, given fitness and technical assistance, make perfect? I have my doubts, informed by some of the finest writing about the history and performance of samba from the likes of Barbara Browning and Hermano Vianna. These writers suggest to me that good samba must be samba that is meaningful to body, mind and soul. The good sambista is passionately involved, in and through the dancing, in the articulation of a contested history of race and gender relations in Brazil. The good sambista is driven with passionate intensity to express, celebrate and protest the experiences of everyday Brazilians, particularly of Afro-Brazilians in the favelas. No matter how adept, well taught and practiced, I could probably never samba well because, though a close, occasionally participant observer in Brazil, I’m not driven by roots and everyday life experience to express through feet, thighs, belly and arms, a Brazilian identity and soul.

However, there are several things to consider before that doubt puffs up into a full-fledged excuse for samba ineptitude. First, there’s Barbara Browning herself. This New Yorker not only writes authoritatively about samba but is recognized in Brazil and internationally as a foremost samba performer. True, she has spent years of her life in Rio and Salvador, and has immersed herself in Afro-Brazilian communities of Candomblé (Afro-Brazilian religion) and Capoeira (Afro-Brazilian martial art). But she stands (or dances) as a case demonstrating that an outsider can become not just a competent but a creative and inspiring sambista.

Then there are questions about the thesis that the good sambista must be driven by a sense of and a quest for particular Brazilian meaning. To watch Sambadrome videoclips is to be drawn close to the conclusion that it’s all about sex, stupid. Refusing that reduction, it still seems that samba means different things to different, but more than competent, dancers: ergo, a specific Brazilian meaning may not be the necessary source of the vital energy good samba requires. So it looks as though I might have run out of lame excuses for my lame samba.

However it’s time for me to shuffle off, the better to focus more sharply on samba and its place in Brazilian society and culture. To that end we must give further attention to the question of samba’s meaning to dancers. And there are two meanings of a specifically Brazilian kind that must be considered.

Browning considers samba to be resistance in motion. She tells us that her teachers and the ordinary but awesome sambistas she has danced with in Rio and Salvador are, albeit with varying degrees of self-consciousness, defining in dance positive Afro- Brazilian identities. As they do so, they seek to reject in movement the oppressions of the past and the racial and gender identities that are imposed in the present. For many of her sambistas, the secular dance is founded in and continuous with the sacred rhythms and dances of the Afro-Brazilian religion, Candomblé. The energy and creativity of the dance is ultimately the energy and creativity of the orixás (the African spirits). Clearly, these meanings may energize a particular subset of the Brazilian population, comprised especially but by no means exclusively by Afro-Brazilians. Browning’s sambistas are fired to dance to assert their particular identities in a Brazil of unregulated heterogeneity.

But as Browning herself acknowledges, millions of Brazilians since the 1930s have danced samba enthused, not to resist, but to be included in and to celebrate what they believed to be Brazil’s glorious distinction, its racial democracy. The myth of a carefully modulated and harmonious multiracial heterogeneity, symbolized and achieved in samba, moved many dancers. To dance samba was to acknowledge and help realize the promise of centuries of physical miscegenation in the making of a modern, complex national society. In the 21st century, it is sometimes hard to recall that for the middle decades of the 20th, samba was indeed the national music and dance of Brazil. The sounds of traditional samba are growing ever fainter, long since swamped by successive waves of bossa nova, sertaneja music, Brazilian rock, MPB, samba-reggae, mangue beat and homegrown hip hop. But testimonies in Sérgio Cabral’s interviews with great figures in Rio’s samba schools, and stories that Vianna tells us, affirm samba’s former dominance. Moreover, they show us musicians, dancers and performers themselves proclaiming samba as Brazil’s racial democracy in dance.

Initially, the connections between miscegenation, samba from Rio’s favelas and the making of a modern racial democracy existed only in the minds of members of a modernist cultural elite—pre-eminent among them Recife’s Gilberto Freyre. Having been excited by samba and the racial and cultural synergies he encountered in Rio in the 1920s, Freyre went on to write the classic account of miscegenation in Brazil as a source of a distinctive, vital and strong Brazilian society. His narratives and word-pictures in The Masters and the Slaves (1933) quickly informed the image of a shared national community, grounded in miscegenation, held by many Brazilians, even across racial, class and regional divides.

What had been Freyre’s dream, with samba as its central, effective symbol, was well on its way to being a successful national project when the nation-building governments of President Getúlio Vargas helped it along. Vargas first endorsed ethnic integration (read racial mixing) as national policy, and then, throughout the 30s, sought to realize what he called racial democracy through means that included patronage and regulation of samba schools and the diffusion of the Carioca samba-dominated carnaval throughout Brazil. The creativity of sambistas did the rest.

So samba became officially, and by popular acclaim and practice, Brazil’s national dance. And by all accounts, the national dance became the prime means for diffusion of the nation-building story of a unique Brazilian racial democracy. But it was not to stay that way. Well before the end of the 20h century samba had been displaced as most listened and danced to music. The vision of Brazil as a racial democracy that had started with young modernist intellectuals in the 1920s started to wither in the 1980s as a new breed of social scientists de-constructed it as mere hegemonic myth, a means of occluding the realities of racial prejudice, segregation and oppression. And by then, samba itself had become invested with multiple meanings—those discerned by Browning with echoes of Gilberto Freyre’s interpretations included.

Most important of all, though, as a factor in the displacement of samba, important segments of the Afro-Brazilian population started not only to move to other dances, but in those dances expressed cosmopolitan, mid-Atlantic Afro identifications and aspirations that cannot be contained in a Brazilian racial democracy of the Freyre-Vargas mold. For example, Olodum, the best known (nationally and internationally) of the Bahian carnival’s blocos afro has devised and popularized samba-reggae and taken a lead in fostering black pride among young Afro-Brazilians. In song and dance the group rejects and seeks to resist the injustices and exclusions of the supposed racial democracy. It drums and dances for a Brazil of jostling particular identities, some of which will not be made in Brazil—one of the bounds to heterogeneity stipulated by Freyre.

But if samba has lost its place as the national dance central to Brazilian nation-building, it has by no means disappeared. It is still the dance of Rio’s carnaval, and that is recognized as Brazil’s national carnaval, even by such champions of Bahian carnaval as Caetano Veloso. And in Rio, the samba schools, from time to time at least, still display their pride in their mestiço nation. Samba is also to be found inflecting much of the music and the dance that displaces it. Samba-reggae, as its name suggests, melds the 6/8 beat of reggae resounding on the deep surdo drum with samba double triplets and riffs. And those who dance samba-reggae unmistakably dance a samba. The music and the dance express both the new Afro cosmopolitanism, and deep Brazilian roots. There also are other fusions on the global stage. The hip-hop group Black-eyed Peas, for instance, recently collaborated with sambista Sergio Mendes on a new CD. Metamorphizing as it always has, samba may yet be the pre-eminent dance, not of a specific Brazilian national identity, but of the local quest for meaning and identity in globalizing, ever more cosmopolitan Brazil. Failing that, it will be danced for the sheer enjoyment and achievement of the thing.

Rowan Ireland is a former Lemann Scholar at DRCLAS (2001). For more than three decades he has studied religion and politics, and social movements in urban areas in Brazil. He is a researcher in the sociology and anthropology programs and the Institute of Latin American Studies at La Trobe University in Australia.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Dance!

We were little black cats with white whiskers and long tails. One musical number from my one and only dance performance—in the fifth grade—has always stuck in my head. It was called “Hernando’s Hideaway,” a rhythm I was told was a tango from a faraway place called Argentina.

Brazilian Breakdancing

When you think about breakdancing, images of kids popping, locking, and wind-milling, hand- standing, shoulder-rolling, and hand-jumping, might come to mind. And those kids might be city kids dancing in vacant lots and playgrounds. Now, New England kids of all classes and cultures are getting a chance to practice break-dancing in their school gyms and then go learn about it in a teaching unit designed by Veronica …

Dance Revolution: Creating Global Citizens in the Favelas of Rio

Yolanda Demétrio stares out the window of our public bus in Rio de Janeiro, on our way to visit her dance colleagues at Rio’s avant-garde cultural center, Fundição Progresso. Yolanda is a 37-year-old dance teacher, homeowner, social entrepreneur and former favela (Brazilian urban shantytown) resident. She is the founder and director of Espaço Aberto (Open Space), an organization through which Yolanda has nearly …