The Multiplicity of Latin American and Latino Urban Worlds

What City, Whose City?

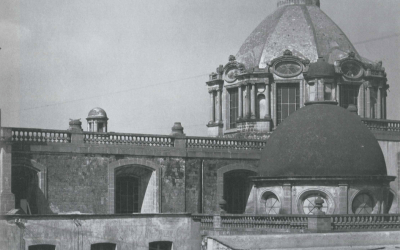

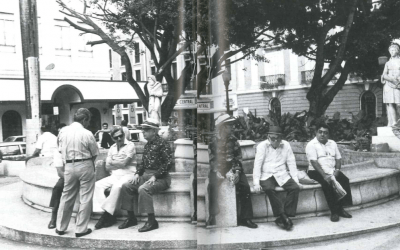

Latin American and Latino placemaking: city contrasts. Photos by June Carolyn Erlick, Magda Kowalczykowski, and Oscar Grauer.

In celebrating Latin America’s cultural heritage, one often hears well-intended people speaking of Latin American cities and Latino place making. It might be useful to ask, however, if there is such a thing as a Latin American urbanism or Latino place making?

In delineating the Latin American city or Latino place making, most often we are offered images or texts that describe particular aspects of the city or place. In the case of the U.S. Latino place making, it is reduced to discussions of mainly immigrant neighborhoods: lower middle class, working class and poorer. These areas enjoy a robust, colorful and almost carnival-like street life, reflecting the ethnic identity of their residents: Mexicans, Central Americans, Puerto Ricans, and increasingly South Americans. Housing styles or landscapes are often are used as spatial markers for Latinitud. Mike Davis, for example, in his Magical Urbanism: Latinos Reinvent the U.S. Big City (London: Sage, 2000) offers a number of brief but joyous celebrations of Latino place making. In doing so he reduces Latino place to the “glorious sorbet palette” of their homes, the creation of gardens in derelict lots, the growth of street use and vibrancy in the parks associated with some Latinos.

What is missing is a more nuanced discussion of the way Latinos make their neighborhoods and places. If you walk through Los Angeles you will find that there is not one Latino place but a myriad of places. Along Alvarado where Salvadorans and Guatemalans come together to meet, eat and shop there is a different palette of color, a different social and spatial sensibility than when visiting the Mexican-American neighborhoods of East LA. And all of these areas of poorer Latinos have a distinctly different feel from more middle class Latino areas in the region. Indeed, many middle and upper middle class Latinos choose to live in what Davis might see as conventional “white bread” suburbs. Even in the most “supposedly Latino” of neighborhoods, the interventions by Latino residents, where they occur—and such interventions are not ubiquitous—only tinker with the larger infrastructure, which resembles that lived in by everyone from the Chinese to Samoans.

Chicago, although distinctly different from Los Angeles, is one of the largest Latino cities in the U.S. Latinos have inhabited neighborhoods that over the years have been home to everyone from Eastern Europeans to African-Americans. There is little fundamentally different in the morphology and forms of the neighborhood in its most recent Latino manifestation.

When I was a child growing up in a mostly Jewish public housing project called Jacob Riis on New York’s Lower East Side, the surrounding streets were filled with Jews, Puerto Ricans, Poles and Italians. Streets tended to house a mix of ethnic groups although each ethnic group still had places that were uniquely associated with their cultural life. Jews had their delicatessens and appetizing stores, Poles their butchers and bakeries and Hispanics their bodegas with tropical fruits, yams and plantains. Although people in each ethnic group most often associated with people of the same group, there was also continual intermixing. Jews went to bodegas, Hispanics to delicatessens or Polish bakeries and so on. At various times and in different and the same places, people in the neighborhood lived both in parallel worlds defined by each ethnic group, and also within a very integrated and heterogeneous world of the community center, the school and everyday activities like sports, eating out and walking. Today Jacob Riis is mostly Latino and African-American, the streets that surround the project still inhabited by Puerto Ricans but rapidly gentrifying and new hip cafes and stores share space with bodegas. But in many respects the neighborhood still has the same feel and the same look.

At the same time over the years, some neighborhoods in East Harlem and Queens have become mostly Latino. In East Harlem there are mostly Puerto Ricans. In Queens there are more Peruvians, Dominicans and Colombians. In these communities there are more bodegas and more Latino eating-places, although the foods, the styles and the sound of the language one would find in Queens would differ from that found in East Harlem. The style of buildings and streets built years ago are different as well in the two areas. One then could ask which is the Latino place, which represents Latinitud? My answer is all and none. They are places where Latinos live and work and thus in an obvious sense Latino. But they are in a diverse city where many Latinos no longer live in areas were Latinos are a majority, where many people other than Latinos shop and eat in Latino neighborhoods and in which different styles and types of Latino are represented. Moreover, they have a feel, a landscape and an urban identity entirely different from the Latino areas of Los Angeles and Chicago.

In Latin America we find the same diversity of forms and lifestyles, the same complex reality. Walking in the Recoleta neighborhood of Buenos Aires, at least before the recent economic collapse, one would encounter fancy restaurants, cafes, and exclusive clothing shops like Armani or Gucci. The streets of Recoleta have more in common with Madison Avenue in New York or Sloane Street in London than they do with villas miseries where the working class and poor live. A resident of the suburbs in the U.S. would feel quite at home in the middle class suburbs of Santiago, Chile with their single family almost ranch style houses but would find the housing based on more traditional Chilean architecture new and different. Nor would people from the U.S. find the many gated homes and communities so prevalent in São Paulo any different from such communities in the U.S. even as they might find the slums of São Paulo strange and frightening. In La Paz, Bolivia, one finds neighborhoods with modernist architecture and what might be construed as a very European lifestyle. On the hills above, one finds indigenous peoples living in areas that dramatically contrast with those in the city center. The people from these areas live in very separate worlds. They sometimes interact in each other’s worlds though, shopping in the city center stores, working as servants. Many of the indigenous are further separated from the center city by language, which many do not speak well, if at all. Which group, which place, and which lifestyle then represents the Latin American city?

As Robert Alexander Gómez suggests in speaking of the Latin American urbanism, “common denominators … are found throughout Latin America, such as the plaza, the patio and the correador,” and there may be “ threads that link multiple Latino and Latin American experiences.” (Gomez 1999 “Learning from East LA” in ” in G. Leclerc, R. Villa & M. J. Dear (Eds.) Urban Latino Cultures: La Vida Latina Thousand Oaks: Sage). This concept is crucial to the notion of Latinitud and a Latin American and Latino sense of place making and urbanity. But it is very selective about the nature of the Latin American urban landscape. Latin American cities also have shopping malls, skyscrapers and new towns that link Latinos in common experiences.

Is the city of Brasilia with its soaring modernist buildings and modernistic landscape designed entirely by Brazilian architects any less Latin American than places like Santa Fe? There, wealthy Anglos more often than not inhabit adobe style houses and dominate the Spanish-derived plazas. Latinos in these areas often live in small ranch style houses in developments on the margins of the city and are mostly found using malls. Modern Latin American cities often combine modernist architecture with what is often called traditional architecture. What then is Latino?

As noteworthy and understandable as attempts to recognize and delineate the Latin American in city making are, the claim that there is such a thing as a Latin American urbanism is reductive of the very urbanism it chooses to elucidate. There is a problem with typifying cities or urban place making as Latin Americana or Latino (or under any other singular rubric). Cities are complex and layered processes. They sometimes involve the same and sometimes different actors, sometimes in the same place and sometimes in different places. There is the city of the elite, city of the poor, city of immigrants and a city of gentrifiers, there is the city of the cosmopolitan and the city of the “native.” There is the city of global capital and the city of local enterprise—one can go on and on. And, there is the city that includes all interacting with one another. These intersect at times; at times they run parallel to each other. What some might call a Latin American city encompasses all these sites.

What we also find is that a city is made up of different actors who live in the city differently even as they share the same physical place, even the same “identity” at times, as residents or citizens of a given city. At times these actors intersect; often they are completely estranged, living in different worlds in which each is unaware of the other. Individuals inhabit a number of different roles in the city; indeed most of us are not actors with one role but play multiple roles.

As individuals, we are often fractured living as we do in different social spaces e.g. village space, neighborhood space, metropolitan space, gendered space, ethnic space, education space, work space, enjoyment space, and consumption space among others. Of course these spaces are often in the same place and populated by the same people. Yet even as we navigate these conflicting and contradictory urban spaces we often fail to recognize them in the way we depict or represent the city.

The problem with defining a Latin American city or Latino place making is that there is an attempt to substitute a part for the whole complex mess that is the city. It does not engage the richness of cities in Latin America. Synecdoche replaces the complex whole and we are left not with Latin American urbanity but some selective cartoon image of some part of its totality.

By recognizing the diversity, the layers, the multiplicity of class, ethnic groups, architectural styles, and urban forms within Latin America and among Latinos, one can finally do them justice by being inclusive and open to all their variety, problems and potentials.

Edward Robbins is a Professor at the Oslo School of Architecture. He taught at the Harvard Graduate School of Design for more than ten years and has written extensively on architecture and on urbanism.

Related Articles

Bogotá: A City (Almost) Transformed

The sleek red bus zooms out of the station in northern Bogota, a futuristic symbol of an (almost) transformed city. Nearby, thousands of cyclists of all ages enjoy a sunny morning on Latin America’s largest bike-path network.

Editor’s Letter: Cityscapes

I have to confess. I fell passionately, madly, in love at first sight. I was standing on the edge of Bogotá’s National Park, breathing in the rain-washed air laden with the heavy fragrance of eucalyptus trees. I looked up towards the mountains over the red-tiled roofs. And then it happened.

Social Spaces in San Juan

My city, San Juan, is a social city. Its character and virtue are best illustrated and defined by the collective and individual memories of its people and those places where we go to spend time in idleness….