The Perils of Eating Feet

The Transformative Power of Trying

I was 19, in love, and eager to gain the acceptance of my boyfriend Guillermo’s family in the mountains of Imbabura, Ecuador.

We sat around the table, smiling, and trying to make each other feel comfortable, motivated by our common love for their 24 year-old son. Colombians from Ipiales, living in Imbabura, Ecuador among Otavaleno Indians, the Acostas understood the difficulties of adaptation. While friendly, this dinner was shrouded in paternal warnings (“una gringa y un gato es igual, ingrato”) and maternal tests. With soup bowls in front of us, we began to eat. This was a family recipe, Guillermo’s sister explained, a delicacy.

Somehow, it smelled familiar, but I couldn’t quite place the aroma. Suddenly, I was whisked back to my New England childhood suburban kitchen, to the smell of a Pennsylvania Dutch delicacy, an old family recipe that evoked for my mother the memory of the Allegheny coal mining community she had left years before. Throughout my childhood, I had refused to even taste “pig’s feet pie.”

Now, here I was in Ecuador, ladling spoonfuls of broth from around the white calf’s hoof standing in the center of the plate. As I glanced around, I noticed that the other plates contained only a fragment of hoof from which Guillermo’s parents, sisters, and brothers extracted a soft whitish substance. I tried to watch them out of the corner of my eye to figure out how they had cracked the hoof open. With a dry bowl now in front of me, I began gingerly tapping the side of the hoof with my spoon. Everyone respectfully ignored the sound and continued eating. Confused, I turned the hoof over, desperately searching for a possible opening. Finding nothing, I picked up my fork, as I had seen the others do, and -to my downfall- my knife, and began to saw. The table fell silent, spoons and forks stopped in mid-air. I looked up to find every set of eyes blankly staring at me. Someone, finally, mercifully, and matter-of-factly stated: “That might take a while.” The entire group burst out laughing. Aware that calf hoof soup was not common fare in the U.S., no one had ever expected me to want to eat the marrow. They believed that in giving me the whole hoof they had spared me the embarrassment of declining. They were wrong. The hoof was so hard, it had to be split with an ax. Once the commotion subsided and tears of laughter wiped away, we resumed eating with a new level of comfort, for in some way it was now understood that although I would never be successful in my efforts in their home, I had tried.

Spring/Summer 2001

Jennifer Burtner is the DRCLAS Brazil Studies Coordinator.

Related Articles

Rigoberta Menchú and the Politics of Food

I think everyone who reads Rigoberta Menchú’s famous 1982 testimonio remembers the part in editor Elisabeth Burgos’s prologue when she describes how she won the Guatemalan woman’s…

Peanuts, Popcorn, Cracker Jack

While peanuts and popcorn were new to 19th century United States, both had been consumed as snacks in the Americas for thousands of years. Peanuts originated in Bolivia, domesticated by…

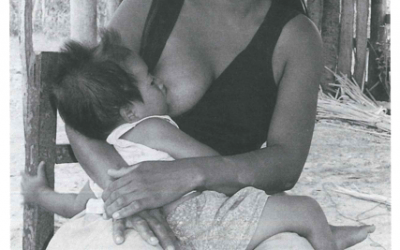

Nutrición, Lactancia Materna y Fertilidad

“2 de febrero, 2000: Es la hora de la siesta en Namqom. Todo está calmo, atemporal, borroso” Yo estoy sentada en la salita de enfermería en en el Centro de Salud. Desde aquí escucho roncar a…