The Postville Immigration Raid

Like a Great Flood

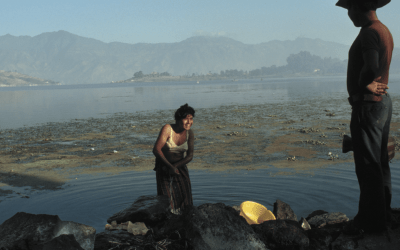

Amputee Rafael Toj lost his foot crossing the U.S. border. His daughter Rosario was saving up money to buy him a new prosthetic foot when she was caught in the raid. Photo by Jennifer Szymaszek

One spring morning two years ago, disaster struck a poor valley in the highlands of Guatemala. A local woman said it was like “a great flood.” Someone else compared it to an earthquake. But this was no natural disaster—it was man-made and happened thousands of miles to the north, in a small northeastern Iowa farm town.

On May 12, 2008, federal officials descended on the Agriprocessors kosher meatpacking plant in Postville, Iowa, in the biggest workplace immigration raid in U.S. history, arresting nearly 400 undocumented workers, most of them from Guatemala. Helicopters whirred over the sprawling plant as hundreds were driven off to the nearby cattle fairgrounds to be processed, jailed and eventually deported.

In the coming months, iconic images of orange-suited plant workers shuffling to detention in chains would place Postville squarely at the center of the U.S. immigration debate. But on this May morning, news of the mass arrests swept through the Guatemalan countryside long before hitting the U.S. nightly newscasts or even the blogosphere.

Most of the arrested workers came from El Rosario and San José Calderas—two neighboring villages wedged between misty volcanic peaks that tower over the colonial tourist town of Antigua. Young men and women from these villages had been making the risky journey north for years. For their families back home, their wages from the plant were an economic lifeline that suddenly had been severed.

“Twenty minutes after the raid everyone here knew we’d been caught,” Willian Toj, one of the first to be deported, told us after arriving in El Rosario. The father of four added, “People here cried here as much as in Postville.”

My co-director Jenn Szymaszek and I were first inspired to start a film project when we read about the Postville raid in a Mexican newspaper. We had been working together—I as a writer and Jenn as a photographer—on stories about how the U.S. recession had affected Mexican villages dependent on migrant cash. We had seen how workers from a particular town or village flocked to specific U.S. destinations, building up cross-border kinship networks. Given the sheer size of the Postville raid, we figured that somewhere a village dependent on Postville was falling apart.

Two weeks later, in Iowa, we met with women from El Rosario and San José Calderas who had been arrested in the raid, but were allowed to remain in Postville to look after their children as they awaited trials. Banned from working, they had been fitted with clunky GPS ankle tags to limit their movements. They told us stories of life and death, of treks through Mexico and long days earning cash in the plant to send back to a mother with diabetes, a father with a prosthetic foot.

When we followed their stories back to Guatemala, the emotional climate reminded us of the scenes of hurricanes or landslides we’d covered in the past. Everywhere we walked, people pulled us into their homes to show us how their lives had changed on May 12.

Guatemalans deported from the United States arrive several times a week, clutching little more than plastic bags, as they pour through a battered metal door in the rear of La Aurora Airport. We met Willian Toj there, rode with him on the back of a pickup truck to El Rosario, and watched as he rushed into his parents’ arms. He’d been working at the plant for only 20 minutes when he was caught. He was penniless and $7,000 in debt, mostly to a local moneylender who had lent him the money for his trip, taking his simple home as collateral. Over the coming months, as many as 200 of his Postville co-workers would return to El Rosario and San José, many of them similarly destitute.

But the raid’s economic devastation didn’t end at a winding dirt road in Guatemala. Postville, a local anomaly for its multi-cultural make-up, and prospering before the raid, saw its economy grind to a halt after losing a large chunk of its population and seeing the meatpacking plant go bankrupt. As a hardware store owner on the main street told us: “When you take 400 people out of a town of 2,000 people, it hurts.”

When people watch our film, they tell us they are moved by the stories of hardship from Guatemala. But it’s the scenes of local Iowans lining up at Postville’s food pantry in the snow, in what a local aid worker called “the heartland of America that feeds the world,” that may linger longest after the credits roll.

Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1

Greg Brosnan is the co-director of In the Shadow of the Raid, a documentary he made with his production partner Jennifer Szymaszek about the cross-border economic impact of the Postville immigration raid. Brosnan, a former Reuters text journalist and Szymaszek, a freelance photojournalist, pooled their skills three years ago to form production company StreetDog Media http://www.streetdogmedia.com. He lives in Mexico City.

Related Articles

Guatemala: Editor’s Letter

The diminutive indigenous woman in her bright embroidered blouse waited proudly for her grandson to receive his engineering degree. His mother, also dressed in a traditional flowery blouse—a huipil, took photos with a top-of-the-line digital camera.

Making of the Modern: An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann

Making of the Modern An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1Related Articles

Increasing the Visibility of Guatemalan Immigrants

Guatemalans have been migrating to the United States in large numbers since the late 1970s, but were not highly visible to the U.S. public as Guatemalans. That changed on May 12, 2008, when agents of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) launched the largest single-site workplace raid against undocumented immigrant workers up to that time. As helicopters circled overhead, ICE agents rounded up and arrested …