The Sound of Garbage

The Landfill Harmonic Orchestra

The recyclers in Cateura, Asunción’s municipal garbage dump, live from the trash and, in many cases, among the trash. The fetid odor carried along by the wind from Cateura to the nearby communities of Bañado Sur is intense, since the area has no sewage system and the service of running water is deficient. Children often work alongside adults picking trash or as street vendors instead of going to school—school attendance is only 40 percent. However, a sweet melody has now emerged among the discarded metal, plastic and smelly refuse: the Landfill Harmonic Orchestra, which in Spanish is known by the more evocative name, la Orquesta de Instrumentos Reciclados de Cateura—the Orchestra of Instruments Recycled From Cateura.

When environmental engineer Favio Sánchez, now 39, arrived in the community eight years ago to work on a waste recycling project, he found the conditions in the dump, one of the focal points of environmental tension in the Paraguayan capital, startling. The dump received—and continues to receive—800 tons of garbage daily. Only a few feet away from the banks of the Paraguay River with its continual threat of flooding, the dump is home to some 2,500 families who squat in small shanty towns near the garbage dump, their primary source of income. These gancheros recycle what the rest of the city has cast aside. Whether it’s cold, rainy or very hot—Asunción can reach temperatures of 110 degrees in the summer—the residents of Cateura pick through the trash to make a few dollars.

To get closer to the families, he began teaching music to the children who approached him, curious about this stranger in the dumps. None of the kids could afford a musical instrument to practice on. After a day of musical lessons, they would always go home without being able to feel an instrument in their own hands. But soon they got the idea of looking for raw materials in the trash, recycling them and transforming them into guitars, cellos and flutes.

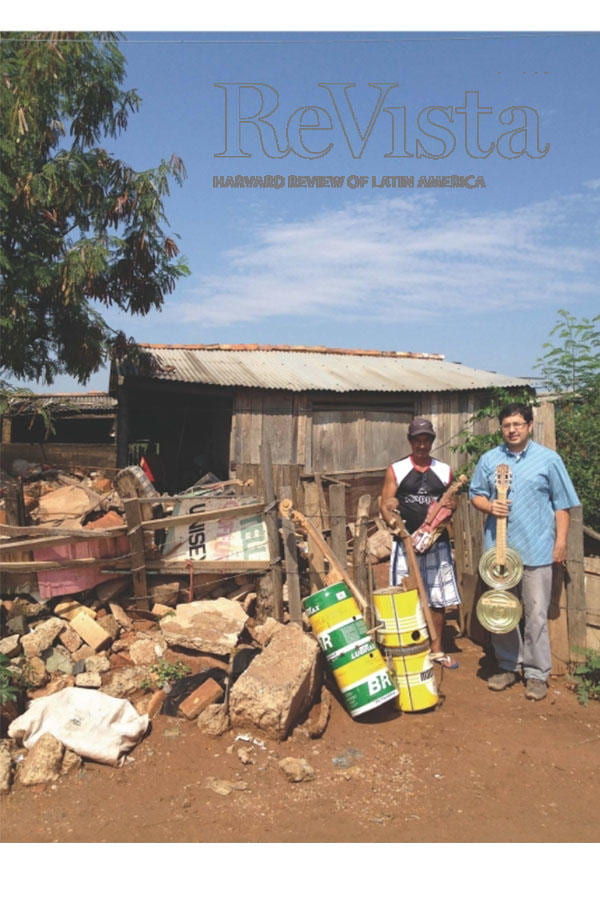

Nicolás “Cola” Gómez, a Cateura recycler, took charge of the creation of the string and wind instruments. Although he had never seen a violin, his sheer determination and talent in carpentry transformed him into a “trash magician.” Oil tin cans, bottle caps, pieces of metal tubes, even forks, all served to put together musical instruments. The children learned to play Mozart, Beethoven, Henry Mancini and even the Beatles on their makeshift creations.

The project has grown from a mere ten children in 2006 to more than two hundred music learners today, with 35 children actually in the orchestra. All of them live in conditions of extreme poverty, with all that that signifies: broken families, street violence, drugs and alcoholism. Although it rises out of the trash, the project’s emphasis is not only on its environmental value, but in what it teaches children about effort, cooperation, tolerance and leadership—qualities that are all too often absent from their communities. To be a member of the Landfill Harmonic Orchestra requires commitment. Sánchez puts much emphasis on shaping values, but cautions that it’s too early to measure results. “Time will tell,” he says.

Thanks to the documentary by Juliana Penaranda-Loftus, Landfill Harmonic, the children of the orchestra have begun to travel to travel far and wide within Paraguay and overseas, telling the story of the recycling of instruments and the recycling of lives. The rock group Metallica even chose them as the opening act in its last tour around Latin America. The orchestra has now received donations of new instruments; it also now has its own place to rehearse and receive music lessons. “But everything doesn’t get resolved with a trip to Europe,” cautions Sánchez. He points out that the children’s daily reality is much different from what they witnessed in Düsseldorf, Boston and Madrid. The changes Sánchez hopes to achieve in the children’s lives are slow, one step at a time.

Even more than the craft of music, Sánchez hopes to impart to the children the concept of making an effort and of gaining perspective on their own lives, making their own decisions. Sometimes it is just enough to show alternatives for them to take initiative. Nevertheless, daily reality is not easy to confront. Thus, the project supports the families so that students can stay off the streets and continue their studies; sometimes, the project contributes to improving houses and providing materials and food. But more than material benefits, the project provides formation and respects their backgrounds, the realities of the difficulties of living in or around the dump.

Their everyday life is difficult, living in the middle of garbage. But in Cateura, garbage also signifies hope. The mountains of discarded trash have transformed themselved into opportunity in a little school. Dozens of children from the garbage dump are learning to see the world in a different way, and the world in turn is learning just what these children are capable of doing.

Tania has learned to play instruments made from recycled materials. Photo courtesy of Landfill Harmonic.

El sonido de la basura

Por Rocío López Íñigo

Cateura, el vertedero municipal de Asunción es uno de los puntos de mayor tensión ambiental de la capital paraguaya. A pesar de recibir unas 800 toneladas de basura al día, los metros que le separan de las orillas del río Paraguay son escasos. El riesgo de inundación es extremadamente alto. Unas 2500 familias viven en pequeños asentamientos ilegales en las cercanías del basurero, el que para muchos es su principal fuente de ingresos. Son los llamados “gancheros”, los que reciclan los deperdicios del resto de los habitantes de la ciudad. Con frío, con lluvia o con calor extremo – Asunción puede llegar a rozar los 45 grados en verano- , los moradores de Cateura seleccionan la basura para después venderla por apenas unos dólares.

Viven de la basura y en muchos casos, entre basura. El fétido olor que arrastra el viento desde Cateura a las comunidades cercanas del Bañado Sur es intenso, no existe un sistema de alcantarillado y el servicio de agua corriente es deficiente. La situación para los niños no es mucho mejor que para los adultos, desde muy jóvenes ya deben ayudar en las tareas de recogida de basura o venta ambulante. El analfabetismo y la ausencia escolar es muy común en estos barrios. Sin embargo, desde hace ocho años una dulce melodía resuena entre la chapa, los plásticos, la mugre y los deshechos: la Orquesta de Instrumentos Reciclados de Cateura.

Favio Sánchez llegó a la comunidad para colaborar en un proyecto de mejora ambiental con los trabajadores de Cateura. Con el fin de crear un vínculo más estrecho con las familias, comenzó a enseñar música a los niños que se fueron acercando. Ninguno de ellos podía permitirse un instrumento clásico con el que ensayar . Después de un día de lecciones musicales siempre volvían a casar sin acariciar la música con sus propias manos. Pero pronto llegaron a una solución adecuada a sus recursos: buscar en la basura materiales todavía útiles, reciclarlos y convertirlos en guitarras, chelos y flautas a las que arrancar unas notas.

El encargado de realizar estas piezas tan especiales fue Nicolás “Cola” Gómez, reciclador de Cateura. Aunque nunca en su vida había visto un violín, su determinación y habilidad en carpintería le convirtieron en el “luthier” del vertedero. Latas de aceite, chapas de botella, pedazos de tubos metálicos. Todo le sirve a este mago de la basura para componer sus instrumentos.

El proyecto comenzó en 2006 con apenas 10 niños y hoy en día cuenta con más de 200. Todos ellos viven en condiciones de pobreza extrema, con todo lo que ello significa: familias desestructuradas, violencia en la calle, drogas, alcoholismo. Aunque surge de la basura, el acento del proyecto no sólo se encuentra en su valor ambiental, sino en la oportunidad para formar a estos niños en valores de esfuerzo, convivencia, tolerancia o liderazgo. En muchas ocasiones estas cualidades no están presentes en las comunidades y los pequeños crecen sin una orientación clara – las escuelas no son por lo general un centro de motivación y el contexto familiar dificulta el desarrollo óptimo de los niños. Formar parte de una orquesta que les pide compromiso y les devuelve perspectivas sobre su vida es uno de los pilares básicos sobre los que trabaja Favio. El resultado como él dice, “lo dirá el tiempo”.

En los últimos meses y gracias al cortometraje documental de Juliana Penaranda-Loftus, Landfill Harmonic, los pequeños de la Orquesta de Instrumentos Reciclados Cateura y su historia han cruzado fronteras. Están en continua gira dentro y fuera del país. Se codean con los más grandes y ya han tocado en los principales escenarios de Latinoamérica – el grupo de rock Metallica les seleccionó como teloneros en su última gira por el continente. Han recibido donaciones de instrumentos nuevos y han podido invertir en un pequeño local donde ahora reciben las clases y pueden ensayar con tranquilidad. Pero como Favio se encarga de recordarnos, “no todo se arregla con un viaje a Europa”. Estas experiencias son extremadamente positivas para la formación integral de los niños, pero su realidad es muy diferente a la que ven en Düsseldorf, Boston o Madrid. Los cambios que se pretenden realizar en la vida de los pequeños son paulatinos, se conseguirán poquito a poco, paso a paso.

Esfuerzo es lo que Favio quiere legar a estos niños, para que miren con perspectiva su vida y tomen sus propias decisiones. A veces, sólo hay que mostrarles otro camino alternativo, enseñarles que la dirección de su vida no tiene que ser la misma que ahora determina su presente, que ellos pueden tomar la iniciativa. Y aunque muchas facetas de su realidad no son fáciles de enfrentar, Favio quiere luchar por que no sea la falta de oportunidades lo que les frenó. Por eso, el proyecto intenta cubrir todo lo posible: apoyan a las familias para que los jóvenes continúen sus estudios y se mantengan alejados de las calles; en ocasiones también se contribuye a la mejora de su vivienda, provisión de suministros o de alimentación. Pero sobre todo, y más importante, guían a los pequeños en la cuestión fundamental de su formación desde el contexto en el que viven y el respeto por su entorno.

Su día a día es duro, vivir entre basura y desechos debe ser difícil. Pero en Cateura, basura también significa esperanza. Los montones de residuos se convierten en oportunidad en una pequeña escuelita. Y ahí, por lo menos los más pequeños, ya están definiendo un camino más sustentable. Monedas oxidadas, cubiertos viejos o tapas de botella vuelven a ser útiles de la mejor manera: construyen una nueva forma de mirar el mañana de decenas de niños del Bañado Sur.

Winter 2015, Volume XIV, Number 2

Rocío López Íñigo is an Erasmus Mundus MA Global Studies candidate from the EMGS Consortium who has lived and worked as a journalist in Argentina and Mexico, experiencing different Latin American realities.

Rocío López Íñigo is an Erasmus Mundus MA Global Studies candidate from the EMGS Consortium who has lived and worked as a journalist in Argentina and Mexico, experiencing different Latin American realities.

Rocío López Íñigo is an Erasmus Mundus MA Global Studies candidate from the EMGS Consortium who has lived and worked as a journalist in Argentina and Mexico, experiencing different Latinamerican realities. She currently lives in Germany and hopes to eventually pursue a PhD in International Relations.

Related Articles

Garbage: Editor’s Letter

Religion is a topic that’s been on my ReVista theme list for a very long time. It’s constantly made its way into other issues from Fiestas to Memory and Democracy to Natural Disasters. Religion permeates Latin America…

Buenos Aires, Wasteland

English + Español

Walking down Avenida Juan de Garay last week, I passed a giant black trash bag that had ballooned and burst. Orange peels, tomatoes, candy wrappers…

First Take: Waste

Waste—its generation, collection and disposal—is a major global challenge in the 21st century. Cities are responsible for managing municipal waste. Solid…