The Summer School for Cuban Teachers

A Harvard Centennial

A group of Cuban teachers with Superintendent Frye in 1900

A hundred years ago, 1,300 Cuban teachers traveled to Harvard to get the training they needed to cope with the new American-style educational system imposed on Cuba by the interventionist U.S. government. They were women- and a smattering of men- of all ages. Harvard President Charles William Eliot called the visit “a unique occurrence in the history of education”

Last fall I had the opportunity to research documents about the trip at Harvard’s Pusey Library. With a fellowship from the University of Houston’s Recovering the U.S. Hispanic Literary Heritage Project and the hospitality of my friend Doris Sommer, a Harvard Romance Languages and Literatures professor, who generously offered me her home.

I came across an almost forgotten book, La Escuela de Verano para los Maestros Cubanos. (Edward W. Wheeler, Cambridge Press, 1900). I believe this book reflects more eloquently than well-known canonical documents the fears, tensions and uncertainties of the times when the island’s rulers were proving unable to define its future.

The book was planned by a group of 18 teachers, two of them women, and finished and hurriedly published in Cambridge, Mass. that same summer. The book was rushed into print in a few days because one of their group was proposing to publish his own text independently. All of this is related in a “Warning” in which the teachers request tolerance for possible errors in “this sketchy account.” The little book, hardly more than a hundred pages long, is largely made up of factual listings of projects, study plans, schedules and even guides of the U.S. and Boston, as well as words by their North American hosts. However, underlying this apparent neutrality, the book also offers direct evidence, however timidly phrased, of the experiences –more collective than personal– of the Cuban teachers who participated in this unprecedented enterprise. Even more surprisingly, it clearly states their ideas about the future status of Cuba.

The journey was also intended to allow the teachers to get to know their hosts, and, above all, to make sure that the host country would become informed about its guests. U.S. interest in the Cuban visitors is conspicuous in extensive press coverage of their stay, not only in Cambridge and Boston newspapers, but in many other East Coast publications. This strange condition of “visited visitors” is evident in passages like the one titled “Photographs of Cubans”:

Whoever can count the stars in the sky can estimate the number of photographs that circulate, found in every store, passed from hand to hand, that illustrate newspaper and magazine articles and every notice that is published […] Finally, in each and every one of the places visited by the Cubans, there is an active and practical industry that focuses on them and prints their images…

Photographs … taken in Cuba before we left have been reproduced here, in all sizes and in all forms, and they have been made into pictures to decorate large rooms [and] into posters to send to other countries […] (45-46)

But when it came to getting better acquainted with their hosts, the teachers expressed their familiarity with the images and topics about the United States described in earlier Cuban travel accounts. Their new experiences reinforced these impressions, but also caused them to be reformulated. For example, the case of “the North American woman” with her habits and independence had evoked contradictory opinions in other travelers. However, the Cuban teachers unanimously considered these role models as positive.. Thus the sight of men and women bathing together on the beach, which “startled the Cuban visitors, causing the cheeks of our ladies to flush in modest astonishment”, came to be considered a “natural” act (37-38); Cuban women teachers took up riding bicycles, peddling them with a flourish through the streets and byways (39). They were eager to teach the North Americans how to dance “danzones, habaneras, the zapateo, tropical waltzes and other steps” (39); and they were enthusiastic about establishing women’s clubs in their future republic (58).

There are many other details that flesh out the portrait of Cuban emigrants described by other chroniclers, Hispanic American 19th century writers who have described the consumer-eagerness of travelers, similar to that of contemporary Cubans who travel to the United States. According to these descriptions, the day after “expedition members” received their salary payments, they caused a crisis in the Cambridge post office. Only one clerk was on duty to handle money orders, when “almost every one of the teachers went there to send money to their families.” After lunch, they caused crunches in local stores where they rushed ” to stock up on those items they found indispensable.” (98-99) Similarly, the authors stress that customs such as baseball adopted from North Americans had taken hold in Cuba way before their trip. Cubans enjoyed baseball and other North American customs “as actors and as spectators” (39). These imports, which affected the construction of Cuban popular culture, have been analyzed recently by scholars such as Roberto González Echevarria’s The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (Oxford University Press, 1999).

In addition to the abundance of details relating to the journey’s explicit goal, as evidenced in the number of pages intended to certify with “official documents” –as we just mentioned– that they dedicated all their time to serious study, the book also provides evidence that for it authors, the journey also had a more important basic goal. They wanted to reinforce the importance of independence for Cuba and to publicize the need for that independence.

With that goal in mind, the teachers reproduced official statements by the trip’s organizers, like Mr. Alexander Everett Frye, who concluded a speech by assuring them that “All Cubans want independence for Cuba, and I have reason to believe that they will soon have it”, (52) and the Mayor of Cambridge who “stated in an almost official way that Cuba would very soon be independent”, (96) or President Eliot of Harvard who urged the formation of women’s clubs similar to those in the United States in those parts of Cuba where they were appropriate, since they would contribute to prepare Cuban women “for civil life in a soon to be established era.” (57)

These statements contrasted with the fact that the pages taken from the guide to the United States described the country as including “various groups of islands, the most important of these being the Phillipines, Hawaii and Puerto Rico.” (67) The teacher-chroniclers text exclaims near the beginning of the book, “May God grant that Cuba may soon be elevated to the status of sovereign nation.” (18) The last chapted concludes emphatically, “Long live the Cuban Republic!” (100)

Both formulations of the future independence of Cuba seem to find their most eloquent expression in the paragraphs ofLa escuela de verano para los maestros cubanos that I transcribe below, and in the words of a Harvard professor recalled in a chapter of Fundación del sistema de escuelas públicas de Cuba: 1900-1901 (Havana, 1954) by the most famous of those Cuban teachers, Ramiro Guerra.

With these words, I conclude this anticipation of a commemoration and –surely– a related debate, which I am confident will contribute to a better understanding of the complex relations between Cuba and the United States.

“When we arrived in Cambridge and went to our assigned housing, our delegation encountered something that so moved and electrified us, that we were unable to contain our feelings of joy and gratitude: there was our beautiful and beloved tri-colored flag. What we felt will be understood by anyone who has been in an analogous situation; it will be understood by our valiant brothers, the liberators, when they recall the moment when, wandering through the fields of Cuba, they came across a camp with that flag.

“Day after day, during the school sessions, the flag has remained in place. It was also been hung in many stores and homes?. More than 3000 little Cuban flags were distributed among public school children gathering at the Boston Common to celebrate the Fourth of July?who waved their flags with enthusiasm for the Cuban teachers visiting Harvard.” (8-9)

Ramiro Guerra recounts the equally passionate words of a Harvard professor specializing in the history of the Spanish colonies. He told the teachers, “You, men and women teachers of Cuba, can admire the greatness of this country, endowed with liberty and democracy; but you should not allow yourselves to be dazzled by this because each nation (pueblo) conscious of its obligations and rights should be able to construct its own destiny.”

Winter 2000

Luisa Campuzano, a professor at the University of Havana, directs the Women’s Studies Program at the Casa de las Américas and the Revolución y Cultura magazine. Campuzano is writing a book on Cuban travelers to the United States in the 19th century. She also lectured to Harvard students in the “Havana in Literature’ 3” Cuban Study Tour last month and led them on a walking tour of Havana.

Related Articles

Isabelle DeSisto: Student Perspective

encountered the first obstacle of my trip to the Isla de la Juventud before I even left Havana. Since American credit cards don’t work in Cuba, I couldn’t buy my plane tickets online. But that…

Honoring Humanity: An “Interview” with Richard Mora

Mauricio Barragán Barajas: Why don’t we begin by having you introduce yourself? RM: Alright. I was born in East Los Angeles, and grew up in Cypress Park, a barrio in…

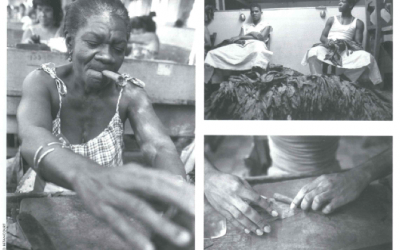

Tobacco and Sugar

“Tobacco and Sugar” is the course that focuses American literatures on the Caribbean, and that acknowledges the unavoidable importance of monocultures for cultural studies. Much of the…