The United States and Guatemala

The Force of a Myth

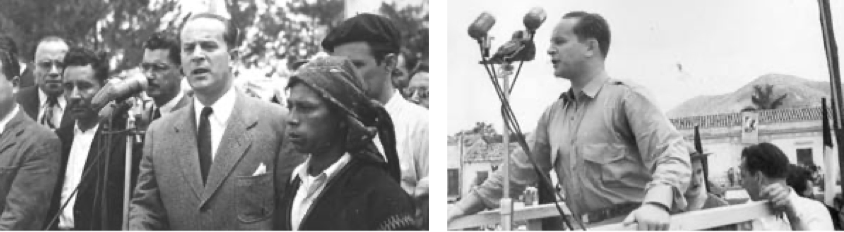

The election campaign took Jacobo Arbenz to virtually every corner of the country. Photo courtesy of Oscar Pelaez Almengor an dthe Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala.

The figure of Guatemala’s overthrown President Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán powerfully illustrates lost hopes and dashed dreams, what could have been and wasn’t. It portrays, in essence, the life of men and women in Guatemala with its marvels and miseries. And in the same manner, it illustrates, for better or for worse, the force of a myth that has grown in the past fifty years.

Today, it is no secret that the United States financed and directed “Operación Éxito” that led to the overthrow of the government of Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán in 1954. Neither is it a secret that many Guatemalans participated as mercenaries in Arbenz’ defeat. There is, on this point, a shared responsibility that Guatemalans have not fully assumed.

On June 27, 1954, more than 50 years ago, Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán, the constitutionally elected president of Guatemala, resigned his post. In his farewell speech, he declared that his decision was based on the fact that he did not want a bloodbath among Guatemalans. How wrong Arbenz was…the bloodbath lasted for almost half a century and political instability a fact of everyday life since then. The political life of Arbenz Guzmán illustrates the lights and shadows of Guatemala’s contemporary history.

OCTOBER 20, 1944

At dawn on October 20, 1944, Lt. Colonel Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán, dressed in civilian clothing in the midst of a group of students, burst into the Honor Guard, already under the control of Francisco Javier Arana. The insurgents captured the Guatemalan Army’s most modern arsenal of weapons, including several armored cars. The skirmish between the rebellious troops and those loyal to dictator Jorge Ubico’s chosen henchman Federico Ponce Vaidez lasted the entire day. The insurgents finally won, with Arbenz Guzmán playing a leading role in the uprising. However, Arana’s command of the armored vehicles was decisive in the victory. Together with the civilian Jorge Toriello Garrido, Arbenz and Arana became the heads of the first government of the October Revolution. Both rose to the position because of their participation in the military uprising, Arbenz as one of the officials of the “School” (educated in the military academy) and Arana as one of the “line” (officials who rose through the ranks by their bootstraps).

Later, during the government of Juan José Arévalo (1945-1951), Arana served as Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces and Arbenz as Defense Minister. Both were the most influential Army officials of the October Revolution.

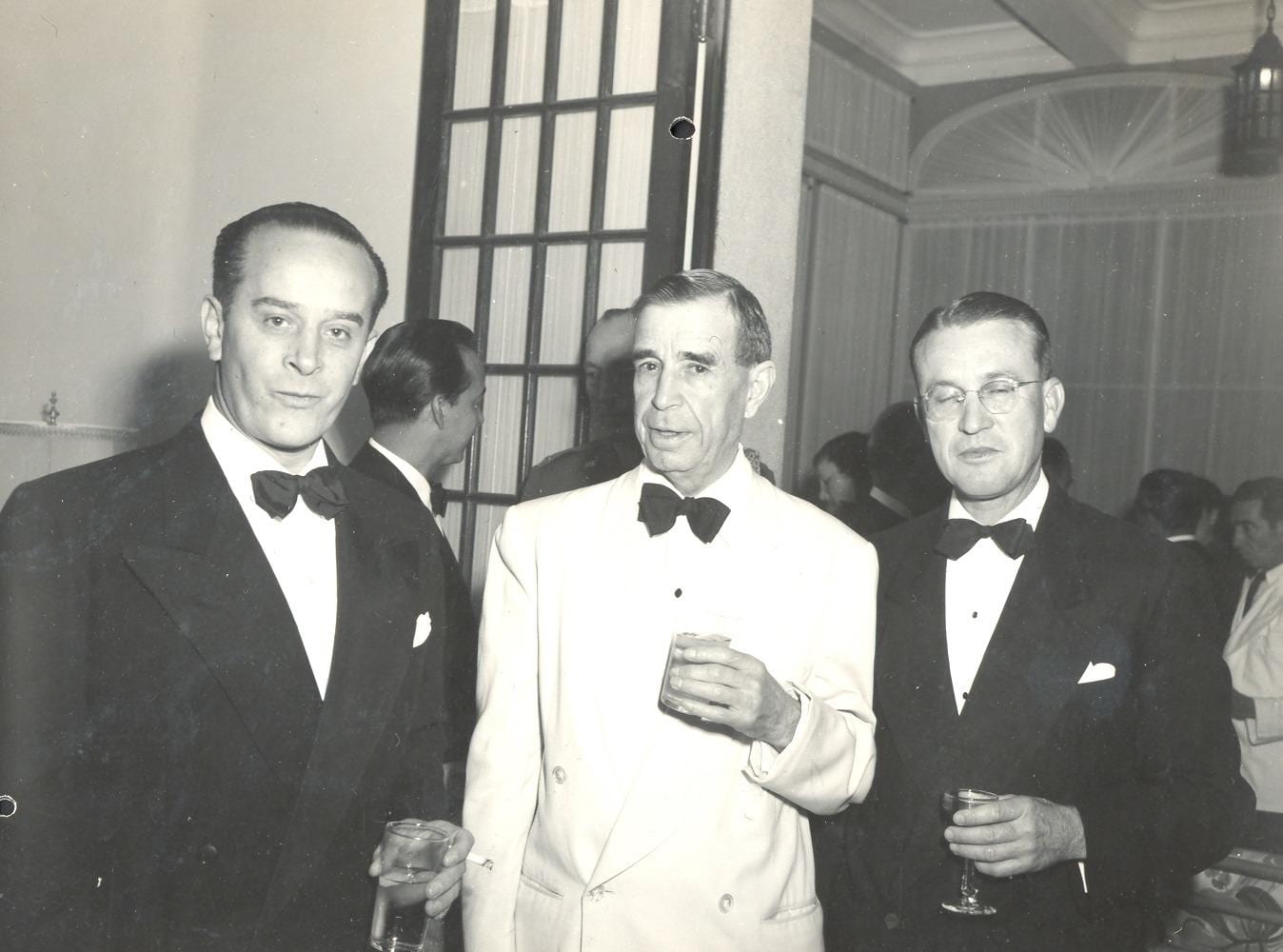

Photographs courtesy of Oscar Pelaez Almegor and the Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala.

THE DEATH OF FRANCISCO JAVIER ARANA

Major Francisco Javier Arana, enticed by sectors wanting to overthrow the Arévalo government, became a conspirator. Emboldened by the president’s lack of firmness, Arana went to Morlón in Amatitlán on July 18, 1949 to recuperate a cache of arms intended for Arevalo’s use by the Caribbean Legion, the so-called “Legión del Caribe.” This was the awaited moment. Arévalo contacted Arbenz, who left the capital with his men in two vehicles. His companions included Colonel Felipe Antonio Girón, Commander of the Presidential Guard, his chaffeur Francisco Palacios and his assistant Major Absalón Peralta. The force that attempted to detain Arana was led by Lt. Colonel Enrique Blanco and Alfonso Martínez, the head of the Congressional Armed Forces Committee. At the bridge known as the Puente de la Gloria, Arana’s vehicle was intercepted, immediately producing crossfire. Arana, Peralta, and Blanco were killed, and others were injured, including Martínez. The news of Arana’s death spread like wildfire, and within a few hours, the most important military barracks in Guatemala City rose up against Arévalo.

The armed insurrection lasted for several days. However, Arbenz – leading the sector of the Army loyal to Arévalo – won the battle. The defeated military men remained thirsty for revenge. Arévalo never sufficiently explained the circumstances that had led to Arana’s death, leading to rampant rumor.

THE ELECTION OF JACOBO ARBENZ GUZMÁN

Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán won the presidency with a clear victory over his opponents. Arbenz’ role in July 1949 during the uprising following Arana’s death and his firm support of Arévalo’s government had earned him the respect of political leaders and the Army. Political party leaders believed that Arbenz was somebody who could unify the different political currents stemming from the October Revolution. Towards the end of 1949, political parties, the Partido de Acción Revolucionaria (PAR) and the Renovación Nacional (RN), both in the government, were preparing to give their support to Arbenz. However, the electoral strategy was distinct; a group of large landholders and industrialists Quetzaltenango, having known Arbenz for many years, formed the Partido de Integridad Nacional (PIN) at the end of 1949 to back him. On February 5, the PIN declared Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán to be its presidential candidate. The PAR and the RN followed shortly afterwards.

After an election campaign that took Arbenz to virtually every corner of the country—the images from which illustrate this article— between November 10 and 12, 1950, Arbenz was declared victor at the polls. Of the 404,739 votes cast, Arbenz won 258,987, Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes obtained second place with 72,796 votes. This indisputable victory carried Arbenz to the nation’s presidency March 15, 1951, with a government program that sought to modernize the nation or, in Arbenz’ own words, “to convert Guatemala into a modern capitalist country.”

THE AGRARIAN REFORM

Arbenz signed the Agrarian Reform Law, Decree 900, on June 17, 1952. According to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), its objectives were to “develop the capitalist economy in Guatemalan agriculture through the abolition of the semi-feudal relations between landowners and workers, moreover, it sought the improvement of cultivation methods through adequate assistance.”

The rapid and complete application of the Law of Agrarian Reform, apart from its benefits, triggered a series of problems. On the domestic front, the agrarian situation with its latent conflicts was pushed into political and legal action. The long conflicts over the land among different communities were daily, weakening the government’s support among strong sectors of the population because of this. The conflict between merchants and industrialists against large landowners, produced by the agrarian reform, undermined the government’s alliance with key economic and political sectors. Finally, the open conflict against multinational interests, especially those of the United Fruit Company, complemented by the anti-imperialist rhetoric of the government, added one more hostile element to an already existing problem. As the Canadian historian Jim Handy has suggested, perhaps the agrarian reform was the “revolution’s most beautiful fruit,” but also the nails of its coffin.

The election campaign took Jacobo Arbenz to virtually every corner of the country.

THE RETALIATION

Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán confronted increasing discontentment about his policies on the part of the Guatemalan elite. The industrialists and merchants abandoned him because of his association with radicalized groups, especially the Partido Guatemalteco del Trabajo (PGT, the Communitst party founded in 1949). The Catholic Church declared war on his government because of the confessed atheism of some of the leaders of the revolutionary left. In those years, there was a war to the death between religious and socialist ideas. The venerated Christ of Esquipulas was used as a symbol to spear the campaign against revolutionary ideas in the name of faith and religion. The army was divided even more after the death of Francisco Javier Arana, and the counterrevolutionaries offered their services to the U.S. State Department to head up whatever rebellion that would promise to overthrow the government. The large landowners were the most affected group because of the application of the agrarian reform, and they had a better reason than anyone to hate Arbenz and his government. Finally, the anti-imperialist language and legal actions by the government against the United Fruit Company, stimulated the intervention of the United States on behalf of the interests of the multinational corporations. The States Department financed approximately $3 million for a campaign of psychological warfare, airplanes and a mercenary army to overthrow the government.

Nevertheless, the principal achievements of the October Revolution outlived its promoters; the domestic market has been expanded; trade and industry have grown, and Guatemala is now a modern capitalist country with an emerging democracy in the process of consolidation. The patch laid out by the October Revolution has finally become a road and Guatemala today is surely what Arévalo and Arbenz desired fifty years ago.

Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán, la fuerza de un mito

Por Oscar Guillermo Peláez Almengor

El domingo 27 de junio de 1954, Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán Presidente Constitucional de la República de Guatemala renunció a su cargo. En su discurso de despedida argumentó que su decisión se basada en el hecho de no desear un baño de sangre entre guatemaltecos. Cuanto se equivoco Arbenz…. el baño de sangre se prolongó por casi medio siglo y la inestabilidad política ha sido moneda corriente en Guatemala desde entonces. La vida política del Teniente Coronel Arbenz Guzmán ilustra las luces y sombras de la historia contemporánea de aquel país.

El 20 de octubre de 1944

En la madrugada de día 20 de 1944, Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán vestido de civil y mezclado entre un grupo de estudiantes irrumpió en la Guardia de Honor, cuando estaba ya bajo el control de Francisco Javier Arana. Los insurgentes tomaron el arsenal más moderno del ejército guatemalteco, incluyendo varios blindados. Las refriegas se prolongaron a lo largo de todo aquel día entre las tropas sublevadas y los fieles a Federico Ponce Vaidez heredero de Jorge Ubico. El triunfo final fue para los alzados en armas, Arbenz Guzmán jugó un papel protagónico durante el levantamiento. Pero, Arana fue decisivo al frente de los blindados. Debido a su participación y por ser Arbenz de los oficiales de “escuela” (educados en la escuela militar) y Arana de los de “línea” (oficiales que por sus propios méritos ascendían en la jerarquía castrense), ambos conformaron el primer gobierno de la Revolución de Octubre acompañados por el ciudadano Jorge Toriello Garrido.

Más tarde, durante el gobierno del Doctor Juan José Arévalo (1945-1951), Arana se convirtió en Jefe de la Fuerzas Armadas y Arbenz en Ministro de la Defensa. Ambos fueron los oficiales más influyentes en la filas del ejército revolucionario.

La muerte de Francisco Javier Arana

El mayor Francisco Javier Arana fue tentado por los sectores interesados en derrocar el gobierno de Arévalo y conspiraba en ese sentido. Arana envalentonado por la falta de firmeza del presidente, el día lunes 18 de julio de 1949 se dirigió al Morlón en Amatitlán con el objeto de recuperar un lote de armas destinadas por Arévalo a la “Legión del Caribe”. Este fue el momento esperado, Arévalo contactó a Arbenz quien partió de la capital en dos vehículos. Arana viajó acompañado por el coronel Felipe Antonio Girón, comandante de la Guardia Presidencial, su chofer Francisco Palacios y su ayudante el mayor Absalón Peralta. La fuerza que intentó aprenderlo estaba dirigida por el teniente coronel Enrique Blanco y el jefe del comité del Congreso a cargo de la Fuerzas Armadas Alfonso Martínez. En el Puente de la Gloria interceptaron el vehículo de Arana, inmediatamente se produjo un intercambio de disparos. El resultado final tres hombres muertos, Arana, su ayudante Peralta y el teniente coronel Blanco, otros fueron heridos incluyendo Alfonso Martínez. La noticia de la muerte de Francisco Javier Arana corrió como polvora, a las pocas horas una sublevación contra Arévalo se extendía en los principales cuarteles de la Ciudad de Guatemala.

La insurrección armada se prolongó por varios días, sin embargo Arbenz al frente del sector de ejército leal a Arévalo ganó la batalla. Entre los derrotados quedó viva la sed de revancha. Arévalo nunca aclaró debidamente las circunstancias en las cuales se produjo la muerte de Arana dejando a la especulación popular los hechos.

La elección de Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán

Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán llego a la presidencia con una clara victoria frente a sus oponentes. El papel jugado por Arbenz en julio de 1949 durante el levantamiento posterior a la muerte de Francisco Javier Arana, su firme apoyo al gobierno de Arévalo le había ganado el respeto entre los líderes políticos y el ejército. Los dirigentes de los partidos políticos creían que Arbenz era el hombre que podía unificar las diferentes fuerzas políticas de la revolución. A finales de 1949 el Partido de Acción Revolucionaria (PAR) y Renovación Nacional (RN), ambos en el gobierno, estaban preparados para brindar su apoyo a Arbenz. Sin embargo, la táctica electoral fue otra, un grupo de terratenientes e industriales de Quetzaltenango, habiendo conocido a Arbenz por muchos años, formaron a finales de 1949 el Partido de Integridad Nacional (PIN), para respaldar a Arbenz. El 5 de febrero de 1950 el PIN proclamó como su candidato presidencial a Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán. Dicho acto fue seguido rápidamente por el PAR y RN.

Luego de una campaña electoral que llevó a Arbenz a todos los rincones del país, cuyas imágenes ilustran el presente escrito, entre el 10 y el 12 de noviembre de 1950 Arbenz triunfó en las urnas. Fueron emitidos 404,739 votos, Arbenz obtuvo 258,987, Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes obtuvo el segundo lugar con 72,796 votos. Esta victoria inobjetable llevó a Arbenz a la presidencia de la nación el 15 de marzo de 1951, con un programa de gobierno que buscaba modernizar el país, en palabras de Arbenz: “convertir Guatemala en un país capitalista moderno”.

La reforma agraria

El 17 de junio de 1952 el Decreto 900, Ley de Reforma Agraria, fue firmado por el presidente Arbenz. De acuerdo con la Agencia Central de Inteligencia (CIA), sus objetivos eran “desarrollar la economía capitalista en el agro guatemalteco a través de la abolición de las relaciones semi-feudales entre patronos y trabajadores, además se busca el mejoramiento de los métodos de cultivo por medio de una adecuada asistencia”.

La rápida y completa aplicación de la Ley de Reforma Agraria, aparte de sus beneficios, acarreo una serie de problemas. En el frente interno, la situación agraria cuya conflictividad latente fue empujada a la acción política y legal. Los largos conflictos por la tierra entre las diferentes comunidades fueron cotidianos, minando con esto el apoyo al gobierno de fuertes sectores de la población. Los conflictos entre comerciantes e industriales contra terratenientes, producidos por la reforma agraria, socavo la alianza del gobierno con sectores claves de la economía y la política. Finalmente, el conflicto abierto contra los intereses de las transnacionales, especialmente la United Fruit Company, complementado con la retórica antiimperialista del gobierno le agregó un elemento adverso más a la problemática ya existente. Como lo ha sugerido el historiador canadiense Jim Handy, quizá la reforma agraria fue “la fruta más hermosa de la revolución”, pero también los clavos de su ataud.

La revancha

Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán enfrentó un descontento cada vez mayor en contra de sus políticas de parte de los sectores dominantes en Guatemala. Los industriales y comerciantes le abandonaron por su cercanía con sectores radicalizados del país, especialmente el Partido Guatemalteco del Trabajo (PGT, partido comunista fundado en 1949). La Iglesia Católica le declaró la guerra debido al ateismo confeso de algunos líderes de la izquierda revolucionaria. En aquellos años había una guerra a muerte entre las ideas religiosas y las ideas socialistas. El señor de Esquipulas encabezo la campaña contra las ideas revolucionarias en nombre de la fé y la religión. El ejército estaba dividió aún antes de la muerte de Francisco Javier Arana y los contrarrevolucionarios ofrecieron sus servicios al Departamento de Estado de Estados Unidos para encabezar cualquier rebelión que prometiera derrocar al gobierno. Los terratenientes fueron los más perjudicados con la aplicación de la reforma agraria, ellos mejor que nadie tenían razones para odiar a Arbenz y su gobierno. Por último, los discursos antiimperialistas y las acciones legales promovidas por el gobierno en contra de la United Fruit Company, propiciaron la intervención de Estados Unidos en defensa de los intereses de las transnacionales. El Departamento de Estado financió con aproximadamente 3 millones de dólares una campaña, que incluía guerra psicológica, aviones y un ejército mercenario para derrocar al gobierno.

El día de hoy no es ningún secreto que los Estados Unidos financiaron y dirigieron la “Operación Éxito” con la cual se derroco el gobierno de Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán en 1954, hace más de 50 años. Como tampoco es un secreto que fueron muchos guatemaltecos los que cobraron salario por participar en el derrocamiento de Arbenz. Existe, en este punto, una responsabilidad compartida que los guatemaltecos no han asumido plenamente.

Los principales logros de la revolución de octubre sobrevivieron a sus impulsores, se amplio el mercado interno, el comercio y la industria han crecido, Guatemala es hoy un país capitalista moderno y con una democracia en vías de consolidación. El rumbo marcado por la revolución de octubre finalmente se hizo camino y Guatemala es hoy seguramente lo que Arévalo y Arbenz desearon hace cincuenta años.

La figura de Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán ilustra poderosamente las esperanzas perdidas, los sueños arrebatados, las esperanzas rotas, lo que pudo ser y no fue. Retrata en fin, la vida de los hombres y mujeres en Guatemala con sus grandezas y sus miserias. Así mismo nos muestra, para bien o para mal, la fuerza de un mito acrecentado en estos últimos cincuenta años.

Spring/Summer 2005, Volume IV, Number 2

Oscar Guillermo Peláez Almengor is the Central American Visiting Scholar at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, 2004-2005. He is a professor at the Center for Urban Studies at the University of San Carlos in Guatemala.

Oscar Guillermo Peláez Almengor es Profesor Visitante de América Central del Centro David Rockefeller para Estudios de América Latina, Harvard University, 2004-2005. Es Profesor Titular del Centro de Estudios Urbanos y Regionales de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala.

Related Articles

Introduction: Bush Administration Policy

So it is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny…

International Symposium in Puebla

It is likely that Don Quijote first reached the Western hemisphere—in what was, at the time, lightning speed—as a stowaway. On September 28, 1605, Franciscan commissioners of the…

Adiós 61 Kirkland

For the past eight years, the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies has made its home at 61 Kirkland Street. Countless film screenings, celebrations and roundtable discussions…