The Venceremos Brigade

A 60s Political Journey

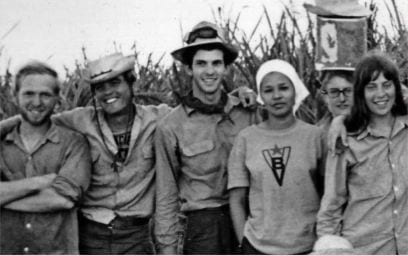

Dick Cluster, third from left, with Cuban and U.S. fifth brigade members of the venceremos brigade. From left to right: Steve, Alberto, Dick, lázara and Nancy. Photo courtesy of Dick Cluster

In the spring of 1961, as a 14-year-old in Baltimore, Maryland, interested in current events, I read in the New York Times about Cubans fighting for freedom at a place called the Bay of Pigs, against a dictatorship that had hijacked a popular revolution. When the forces of good failed to triumph at the Bay of Pigs, I was shocked. A classmate of mine—a precocious member of the Young Socialist Alliance— told me that the operation had been run by the CIA. I could not believe. Hadn’t Adlai Stevenson denied this at the United Nations? Hadn’t the New York Times and other media reported the invasion was a spontaneous action by freedom-loving Cubans?

I tell this story to explain the political journey that led not only me but many of the 216 members of the first contingent of the Venceremos Brigade to violate the warning on our U.S. passports that stated they were “not valid for travel” to the “restricted countries and areas of Cuba, Mainland China, North Korea, and North Viet Nam.” In the years between 1961 and 1969, the Viet Nam war had taught us that what the mainstream media and our government officials said about our country’s foreign policy might not only be mistaken, but might even be a cynical and conscious effort to mislead us in both senses of the word.

Thus the lure of visiting Cuba to cut sugar cane in the Ten Million Ton harvest of 1969-70 was irresistible. It was a chance to see for ourselves whether the devil really had horns and a tail— or, on the contrary, was an angel with a halo. The prospect of doing manual labor with ordinary Cubans meant we were more likely to see the real Cuba than if we sat in formal meetings and speeches. The journey also promised a limited and measurable task—how much cane did we cut—as compared to the complex and sometimes daunting challenge of ending the war or combating racism or bringing radical change to our society. So we flew to Mexico City—the only air link to Havana in the Western Hemisphere at the time—where we were photographed by Mexican intelligence officers and had “Mexico D.F. CUBA” stamped in large purple letters on our passports so our transgression would not go unnoticed at home. And so eventually we returned, three months later, via Cuban freighter to the Canadian Atlantic port of St. John. In between, we cut cane, asked, listened, looked and argued (mostly with each other).

We lived at the Campamento Brigada Venceremos in rural Havana province near the Matanzas border, flat cane-growing land since its deforestation long ago in the days of the Spanish colony. We lived in canvas tents and gathered in palm thatch meeting and mess halls, the 216 of us and 70 Cuban Young Communists selected to work with us and teach us about the Revolution. In our final two weeks, they and we toured the island by schoolbus, staying in other work camps and recently constructed college dorms. Here are some thoughts I took away from this experience at the time.

- The revolution (that is, the rebellion against Batista and its subsequent socialist institutionalization) had been a great exercise in social mobility and redistribution: Lázara, for example, was the daughter of factory worker who had been imprisoned for trade union activity; now she was teaching high school and studying journalism at the university. Alberto’s father had been a truckdriver; he was teaching high school history, studying art and literature, designing posters. Hugo had been a clothing worker himself; now he was an economist. Former mansions in Havana were dorms for students from the countryside. Our Cuban colleagues debated which former luxury tourist hotel they liked best, since all had been the scene of conferences and retreats. In Oriente we could drive to remote villages, previously isolated from all social services; now we found a clinic, a bookstore, a school.

- Great changes in consciousness were possible, and had occurred. In the 50s, Cuba had been as anti-communist as the United States. Now, our new friends and their families approved the revolutionary reforms. At a youth work camp we visited—much like ours except it had permanent barracks, a longer workday, and did not have ice cream as part of the daily rations—I met a teenager doing guard duty at her barracks. Only the two of us were there, no minders of any sort. She told me her mother had just left for the United States, but she had chosen to stay. “I love my mother,” she said, “but I love the revolution more.”

- Communism did not have to be Stalinist. That is to say, it didn’t need to be a carbon-copy of the U.S.S.R., its culture gray, dogmatic, and always politically correct. In off hours, the camp seemed to teem with spontaneity. If someone had a wooden box and two hands, there would be drumming, music, dancing. Movie posters, even propaganda posters, as well as the new paintings in the Havana fine arts museum owed more to San Francisco psychedelia than Soviet socialist realism.During our travels, our Cuban friends bought up copies of a new novel by a Colombian novelist, published by Casa de las Américas in Havana, Cien Años de Soledad. Later, in Santiago de Cuba, a medical student who had very tentatively suggested we might consider going home and waging armed struggle to bring socialism to the United States, made us a present of his dog-eared copy of the same book. We asked these enthusiasts about the novel, expecting a revolutionary tale. “Well, it’s about this village. . . . Well, you have to read it, it’s very hard to explain,”they replied, neither the village of Macondo nor the concept of “magic realism” being a doctrinal concept that fit into any prepackaged phrase.

- An international new wind could be felt in the contingents participating in the harvest from all over the world, including Vietnamese from both the north and south. However, the most telling vignette was about a personal reunion. Vic, from San Francisco, one of the oldest and most grizzled brigadistas, had fought for the Spanish Republic in the International Brigades. When asked, “what are your politics now?” (a key question for identifying factions and tendencies with which people were associated back home), he would say, “I’m a drunk.” No communist orthodoxy or New Leftist utopianism for him. One day a group of Bulgarian canecutters came to visit and work; with them came their embassy’s cultural attaché. He and Vic (I was told, because I didn’t see it) fell into each other’s arms, in tears. They had not seen each other since Spain, and here they were, at the heart of something that was a continuation, yet different and new. There were some discordant notes, of course. In El Uvero in Oriente, though we met older women who had learned to read in the Literacy Campaign, the bookstore was full of unsold books—and our comrades were ecstatic about finding such a trove, including the sought-after García Márquez novel. When the camp leadership made “proposals” about changes in routine, production targets, and the like, there were no arguments for or against, only a revolutionary duty to rise to the occasion. Trade union leaders we met patiently explained to us that there could be no conflicts between workers and management because enterprises were owned by the revolution which was the workers themselves. All of this, however, paled before the evident enthusiasm for making a new country, not only on the part of the Young Communists but, if more muted by everyday life concerns, of many people we met a random too. That vision continued to inspire me, and it continued to inspire many of us—not only in radical organizing but in political, service, and education work of many sorts since.

Readers of ReVista will be well aware that Cuba today is not the future for which our friends on the brigade were working so hard. The harvest did not meet the goal; a more repressive policy in the arts dominated the 1970s; years of significant economic improvement in the later 70s and 80s were reversed in the 1990s with the end of Soviet aid. The world that our friends’ children got was not the one their parents had planned on bequeathing. (Aside: Nonetheless, I’m quite impressed with the way our friends’ children turned out, and the children of others like them, though that discussion does not fit in this article.)

The Cuban brigadistas with whom I was able to stay in touch now have politics that range from the hope of reinventing Cuban socialism within Fidelismo to constant criticism or cynicism, excluding only association with the U.S.-backed opposition either in Cuba or in Florida. Lázara died in the early ‘90s; by then she had a reputation, among Cubans who casually knew her, as an “honest dogmatist.” But this was her parting thought not long before she died: “We have not resolved the relationship between el hombre (man/woman/the individual) and el poder (the apparatus of power).” In those same years Juan, my former cane-cutting partner who now worked as a translator and interpreter, tried at first to put the best face on things. Then one day he said, “There’s no point in my telling you what I told the visiting Turkish journalists today. You’ve been living here a while, and you know how things are.” A few years later, his wife won the U.S. visa lottery and he somewhat reluctantly moved to Miami, to join many of her relatives and some of his. His plan for this new epoch of his life was to stay out of politics and keep his opinions to himself.

However, this was not what surprised me in my reencounters with Cuban brigadistas in the 90s and since. Rather I was struck that, without exception, they said that what they had told us in 1969-70 was the truth as they saw and felt it then. No one had been treating us like Turkish journalists. What we saw was not completely representative, but it was real. Even more surprisingly, the experience had been as special and intense for the Cuban brigadistas as for us. The explanation for this consensus seemed to boil down to two things:

- We took what they were doing seriously. For them as for us, the utopian project was much in need of validation, and formal delegations and slogans about international solidarity were not completely doing the trick. Further, since the 19th century the United States has always had a Janus-faced character in the Cuban imagination—a potentially dominating power to be resisted, but a source of modernity and fresh ideas and part of Cuba’s synthesizing Spanish-African culture too. That we took our Cuban co-workers so seriously confirmed the seriousness with which they wanted to take themselves.

- They were challenged and excited by our cultural radicalism. Cuban youth in general were curious, or challenged, or puzzled about U.S. “hippies,” but in the day to day exchanges on the Brigade, our counter-culture got more real. Our drug-taking never made any sense to them. Those who spoke English did enjoy picking up our foul language, “fucking this” and “motherfucking that.”.But more deeply, something about our notions of cultural liberation, of new gender roles, of societal reinvention outside the spheres of pure politics and economics—something about that changed their sense of what was possible, or gave them something new to grapple with. One example out of many is the protest waged by North American women against being consigned to piling cane rather than cutting it, and issue on which the Cubans eventually gave in., Similarly, they were stimulated by the process of responding to our incessant questions about how their system worked (and how it didn’t work).

I think we can take the two-way intensity of that trans-national, trans-cultural exchange as another lasting moral of the story. The world is no less in need now than then of new systems, paradigms, visions, call it what you will. Our country, certainly, needs to overcome its arrogance and isolation. Others still need to process their love-hate relationships with us.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: The Sixties

When I first started working on this ReVista issue on Colombia, I thought of dedicating it to the memory of someone who had died. Murdered newspaper editor Guillermo Cano had been my entrée into Colombia when I won an Inter American Press Association fellowship in 1977. Others—journalist Penny Lernoux and photographer Richard Cross—had also committed much of their lives to Colombia, although their untimely deaths were …

The True Impact of the Peace Corps: Returning from the Dominican Republic ’03-’05

I am an RPCV: a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer. For me the Peace Corps was an intense life experience, above anything else. As I continue to reflect on it, I am struck with the many and varied ways in which it continues to affect my life. As a PCV in the Dominican Republic from September 2003 to November 2005, I lived, worked, and learned in a small sugar cane-dependent community two hours outside of Santo Domingo…

In the Shadow of JFK: One Peace Corps Experience

I am often asked about the Peace Corps by students and recent graduates. The most frequent questions are, “why join?”, “what did you do?”, and “what has it meant for your career?” Here is my story. My earliest recollection of international curiosity was in the fourth grade when Sister Margaret Thomas described her experience as a recently returned missionary in Bangladesh. In high school, my sister Mary went to Peru on …