The View From New England

A Preliminary Portrait

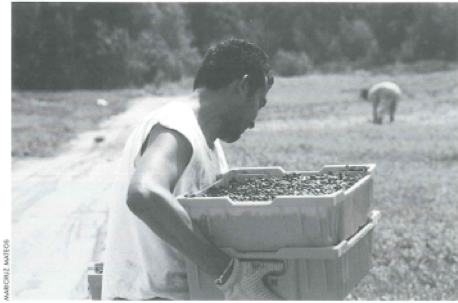

Blueberry Harvest at Cherryfields, Maine, 2001.

The Mexican diaspora has reached New England. Mexicans living in the region today include many types of migrants, long-term and temporary, documented and undocumented. The traditional face of the Mexican presence is rapidly changing as a result. Will this growing population become a true Mexican community in the foreseeable future? This essay seeks to illuminate this question by to providing a first (disposable camera, perhaps?) snapshot of the present mosaic.

Mexicans in New England constitute a diverse,heterogeneous population. Traditionally, they have included distinguished representatives of the best educated and most socially privileged segments of Mexican society, whose enrollment in the region’s academic institutions has in fact tended to increase in recent years. This population, concentrated in metropolitan Boston, has for a long time been one of the better identified, albeit also smallest, components of Mexican presence here. In recent years, an increased number of high school students and part-time ESL and continuing education students have added to the mix. Increased attention to Mexico in New England’s academic circles has contributed a steady flow of researchers and post-doctoral fellows to this normally transient population. A slow process of drop by drop sedimentation linked to these and other flows has also added a more permanently settled group of Mexicans that includes professionals, (university professors, physicians, e-entrepreneurs, etc.), a sprinkle of business owners, and spouses of either Mexican or American citizens.

At the other end of the spectrum, a number of federal convicts have been brought into the picture with the 1999 establishment of a Medical Center in Devens, Massachusetts, by the Federal Bureau of Prisons. Often chronically ill, these Mexicans come from many different states and, along with the small group of Mexican nationals detained in state and county jails throughout the region, constitute a micro-component of the mosaic with very specific needs and characteristics.

However, workers definitively constitute the largest and fastest growing component of New England’s Mexican population. From Boston’s Big Dig to the shift in agricultural production to non-traditional produce such as broccoli in northern Maine, labor markets have created employment opportunities throughout the region for Mexican and other recent migrants, whose growing presence was at least partially reflected in the U.S. 2000 Census. Mexican origin population in Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Vermont grew by 75.9%, from 20, 856 in 1999 to 36, 689 last year, according to the figures for the five New England states covered by the Consulate of Mexico in Boston. Connecticut, covered from New York, isn’t even included in these numbers.

Massachusetts (22,228), Rhode Island (5,881) and New Hampshire (4,590) account for the vast majority of Mexican origin population in these states, with only three highly populated eastern Massachusetts counties (Middlesex, Suffolk and Essex) representing 37.2% of the total. Significant concentrations also exist in other urban areas such as Nashua-Manchester in southern New Hampshire and Central Falls-Pawtucket-Providence in Rhode Island. In fact, the highest growth rate in the region (159.4%) took place in Rhode Island, home to 9.97% of the five state’s total population and 16.02% of their Mexican origin population.

Mexicans in New England, however, reach the region’s furthest corners as both long term and temporary migrants. Maine, the state with the lowest growth rate for Mexican origin population (14.9%) and only 2,756 persons of Mexican origin registered in the 2000 Census, provides interesting examples of both these flows. Relatively stable groups of Mexicans livein the state’s smaller cities and towns like Auburn, Lewiston, Milbridge or Turner, employed in such activities as seafood processing and egg production. However, every yearMaine also hosts a large and increasing number of Mexican temporary workers, not fully accounted for in those census figures. Some come from Mexico under the H2A and H2B visa programs to work in agriculture, landscaping or forestry. Others toil without documents. Some are permanent residents recruited in California for relatively short periods of time. Others are migrant agricultural workers who every year follow the seasons from the South Texas Valley to Aroostook county on the Canadian border, bringing along their families and children, some of them U.S. born. All play a significant role in such traditional and more recent staples of Maine’s economic life as the harvesting of blueberries, asparagus or broccoli.

Perhaps more so than in any other region of the United States, Mexicans in New England, particularly those who live in densely populated areas of Massachusetts and Rhode Island, are immersed in a much larger and diverse Hispanic community. During the last decade the number of Mexican origin residents grew considerably faster than the 62.1% increase of the region’s Hispanic population. The percentage of that wider population that they represent, however, remained relatively stable (and quite small) during the nineties: from 6.09% in 1990, it only grew to 6.61% in 2000. Maine and Vermont, the two states with the smallest Mexican origin population, are relative exceptions, with Mexicans accounting for a much larger proportion of their Hispanic population: 29.4%, and 21.3%, respectively. Only in New Hampshire are Mexicans a significant component of both the Mexican origin population in New England (12.51%) and of that state’s Hispanic community (22.4%).

The three characteristics of the Mexican origin population in New England I have summarized help explain a fourth one: its quite limited degree of organization. Reflecting some of the previously discussed additions to the Mexican population in the region, change has also taken place in this area. A handful of organizations established during the nineties in Massachusetts, Rhode Island and New Hampshire by its more stable components have joined the associations of Mexican students that exist in the most prestigious universities of the Boston metropolitan area. Single issue groups dedicated to the defense of migrant workers have been created in Maine. Most importantly, an effort to establish a Federación de Organizaciones Mexicanas de Nueva Inglaterra (FOMNI), in which all these different groups may find common ground, has continued, on and off, since 1998.

Only a very small part of New England’s Mexican population, however, is linked to any of these initiatives, which have still to reach and incorporate, for example, the working class Mexicans who live in the region’s urban areas. The limited presence of formal organization in turn contributes to an also very limited ability to influence political decisions. With very rare and notable exceptions, the more privileged segments of New England’s Mexican population have not joined the region’s political or judicial circles. Furthermore, with the limited exception of the Mexican Association in Rhode Island, community-based organizations have almost no contacts with local political elites.

The still quite limited number of Mexicans living in the region or the splintered nature of their organizations accounts only partially for this absence from most of New England’s decision making circles. Several other factors seem to be at play: Some of the most distinguished Mexican residents in the area, who might otherwise spearhead local political efforts, often focus on the Mexican political arena instead. While only a few are U.S. citizens, enabling them to participate in electoral processes, others even have yet to adjust their immigration status. A particularly interesting, and somewhat paradoxical, situation seems to happen when a significant number of the Mexican population living in a given area comes from the same Mexican locality: Sombrerete, Zacatecas, in Manchester-Nashua, El Refugio, Jalisco, in East Boston, or Alfajayucan, Hidalgo, in Central Falls-Pawtucket. In those cases, both the lack of formal organization and the resulting constraints on political influence may sometimes be related to the existence of de facto communities, with established communication channels and accepted leadership roles for day- to-day needs and activities, whose members may not have perceived any need to formalize such schemes in the relatively hospitable economic and political climate of the immediate past.

As is the case with most of the content of this essay, these and other issues deserve more attention and rigorous analysis. The image of New England’s Mexican population that begins to emerge, even from the preliminary description thus far presented, is certainly richer than the perception of a student-centered community, still prevalent in some circles of both Mexico and the United States. Mexicans in New England constitute a diverse and heterogeneous population, dispersed throughout the region and subsumed in the wider context of the Hispanic community in those urban areas where it tends to concentrate. These three characteristics are likely to remain in the foreseeable future. May the limited degree of organization and influence associated with them change?

There are interesting challenges and opportunities ahead. While diversity and heterogeneity may hamper attempts to establish umbrella organizations such as FOMNI, they also open possibilities for mutually beneficial support among the different components of the Mexican mosaic. The pattern of geographic distribution associated with such diversity complicates efforts to reach all its pieces. At the same time, however, it creates the potential foundation of a truly regional voice. The contextual factor represented by the wider Hispanic community with which the Mexican population shares many problems and concerns may sometimes complicate the perception of a specifically Mexican set of relevant demands, which might help consolidate a sense of common identity. It, however, also offers extremely useful resources for any attempt to communicate with the Mexican population. The support and collaboration of Hispanic community leaders are, in fact, crucial in this regard, since it is frequently only through the pan-Hispanic electronic and printed media -that Mexicans may be reached.

New England’s Mexican population has started drifting towards community. Whether this journey is completed in the foreseeable future will in good measure depend on the efforts of those community and other leaders who have decided to build on the opportunities just recalled in order to face up to the specific challenges of this regional setting.

Fall 2001, Volume I, Number 1

Carlos Rico, A Ph.D. candidate at Harvard’s Government Department, has been Consul of Mexico in Boston since 1999. He would like to acknowledge the very able help of Carlos Yescas and Jorge Torres in reviewing the 1990 and 2000 Census statistics.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Mexico in Transition

You are holding in your hands the first issue of ReVista, formerly known as DRCLAS NEWS.

Over the last couple of years, DRCLAS NEWS has examined different Latin American themes in depth.

The View from Los Angeles

In 1999, on returning home to LA after four years at Harvard and in the Boston area,I ascended to the city of Angels for the annual gala dinner of the premier civil rights firm: the Mexican American…

What’s New about the “New” Mexico

On July 2, 2000, Mexican voters brought to an end seven decades of one-party authoritarian rule. Just over a year later, Mexico continues to feel the repercussions of this momentous victory…