The View from New York

The Poblano Subdiaspora

Tacos from Puebla in New York.

More than 600,000 people from Puebla, Mexico, call greater New York home. Poblanos as those from Puebla are called make up an immigrant population about half the size of Boston. They give New York City and its surroundings the feel of a “little Puebla,” with an abundance of companies like Puebla Foods, TortillerÃa La Poblanita, Que Chula Es Puebla CarnicerÃa, and México Lindo Bakery.

The lack of opportunities for Poblanos in Puebla has created a wave of immigration to the United States. Puebla, Mexico’s fifth most populous state, had an estimated population of 4,700,000 in 1995. The Government of the State of Puebla estimates that about a million Poblanos work in the United States on a permanent or temporary basis.

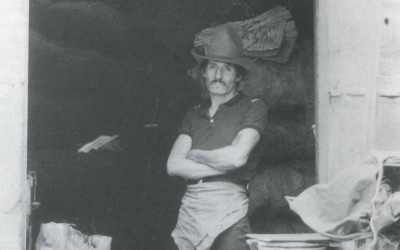

Poblanos have produced successful businessmen like Felix Sanchez, the king of tortillas, who came from Puebla in the 1970s. Although he faced obstacles common for immigrants, Sanchez soon realized that the Mexican community had created a demand for Mexican food products. With his savings, he purchased a used industrial tortilla maker from Mexico and started a small business.

Today, Felix Sanchez is one of the most important Hispanic entrepreneurs in the United States. He has branched out into new ventures such as a cheese factory and a large bakery in New York, as well as a chili factory in Puebla. Sanchez, who has built a very strong relationship with the government of the State of Puebla, is also working to develop programs for helping Mexican immigrants in New York and surrounding areas.

On the other side of the economic scale are the many flower vendors from Puebla. Around-the-clock and on the rainiest days they sell beautiful bouquets of orchids, daisies, roses, and tulips. They can be found in the New York subways or pushing supermarket carts filled with festive flowers through crowded streets.

Immigration scholar Robert Smith suggests that flower vending allows immigrants a measure of dignity. Women, with limited options for employment, sometimes prefer the flower business to work in garment factories. After all, when selling flowers they do not have to tolerate being ordered around. Men, too, often find more dignity in the informal economy of flower selling than in restaurant work.

About 60 percent of the northeastern Poblanos live in New York City, especially in the Jackson Heights neighborhood in Queens. Successful Poblano immigrants in the United States have played an important role in their sub-diaspora’s organization, integration, and development. They remain members of communities in the state of Puebla in Mexico, while cultivating new relationships in their adopted U.S. communities.

Unlike other Mexican sub-diasporas in the United States, the Poblano sub-diaspora is attempting to develop new programs for the assimilation of its members in the United States. The most successful Poblano immigrants in New York lead development committees, which, as documented in their detailed records, are very active in the community.

Poblanos came to New York in the same way as many Mexicans, with guides called coyotes leading them across the border. The history is a long one. At the beginning of the twentieth century, retailers from the Yucatan made constant trips from Progreso and Havana to New York, generating the first contacts of Mexicans in New York and founding the Mexican Center of New York.

Maurilia Arriaga, fondly known as Miss Maurilia, led the first wave of Poblanos in the 1940s. Migrating to New York to work as a cook for a retired American diplomat, she brought a slew of nephews, nieces, and friends to the Big Apple in the 1950s.

In the 1960s came a second wave of Poblanos, many of them from the same small Puebla villages. At the end of the 1960s, when there was much employment in manufacturing and in the restaurant industry, the weekly income of the immigrants ranged from U.S.$50 to $80, considerably more than back home. Industrialists assisted Mexican workers in obtaining temporary resident permits for employment, but numbers remained small. However, New York Poblanos promoted migration to their friends and families back home. Within ten years, there were 6,000 New York Poblanos, and by 1980, 25,000.

The 1982 and 1994 economic crises, as well as the 1985 earthquake, generated an exponential growth in migration to New York. Within the United States, tougher anti-immigrant laws in California caused Poblanos to seek safe haven with friends and family in the northeast.

Although initially caught up with trying to earn a living, 10 years later, some men have attempted to reconcile their New York lives with their Puebla origins, for example through the transnational projects of painting the church or building sewers in their hometown. Often a sort of ancestral racism has emerged, such as in the Puebla municipalities of Chinantla and Piaxtla. Poblanos from Chinantla, with its deeper indigenous roots, typically work in basic agriculture and cattle ranching, while the inhabitants of Piaxla are cattle traders. These differences become emphasized in New York, and Piaxtecos develop greater entrepreneurial opportunities.

The Piaxtecos organize informal religious, civic, and sport celebrations, generating confidence with people of other Hispanic-American ethnic groups, including local politicians, as though belonging to one local elite group.

Although the most successful rarely participate actively, they generally contribute funds or sponsor celebrations, religious parades, dances, and events. Often, personal conflicts develop between the organizers and the sponsors, and accusations of graft and corruption lead to even more divisions. The Poblano community in New York has found group integration to be extremely difficult.

Even social development projects in the community of origin provoke tensions. For instance, say a local community collects funds to paint the hometown church. Then, three community members travel for a weekend to their hometown to give the funds personally. Three months later, the town asks for more money to complete the job. The community in New York returns to collect more contributions and they send them to their hometown again. The committee in New York returns to the town to supervise the works done with its contributions, and they find that the community did not do the painting. The parish priest had to contract painters to do the work. Probably, one of the local members of the committee took part of the money to pay for a celebration or to cover personal necessities. Or, in the worst case, the municipal and parish authorities do not recognize the economic contributions that the migrants made. Consequently, the migrants are reluctant to support another project of social character, resulting in the dissolution of the group. Because they send money home, Poblano immigrants assume leadership roles in their communities of origin, generating division within those communities. Culturally, migrants often break with traditions, some religious, generating a subculture of expression and way of life. They speak Spanglish, and so do their U.S.-born children.

The government of Puebla has sought to overcome some of these ingrained tensions by engaging in a systematic State Development Program 1999-2005. The program seeks to assist Poblanos living in the United States and to generate opportunities for the communities exporting labor from Puebla to the United States. The state government has created the concept of Casas Puebla in several U.S. cities with a concentration of Poblano migrants. A Casa Puebla will advise Poblanos on immigration policy, consular matters, and customs. In addition, it will inform Poblanos of their rights as residents in the United States and increase their bonds and ties with their families in Mexico. Moreover, a Casa Puebla will promote respect for fundamental rights of immigrants and develop campaigns promoting ethnic and social awareness.

The first Casa Puebla in the United States was inaugurated in May 1999 in New York. A non-profit organization with a board of directors, it worked with established Poblano associations, sponsoring education, health, culture, and athletic programs, as well as promoting tourism. New York’s Casa Puebla also promotes programs in which the successful Poblano immigrants invest in their communities of origin in Puebla, creating sources of employment and improving life conditions in the region.

Culture is also an important focus. Well-known singers such as Los Tigres del Norte and Ana Barbara performed at Cinco de Mayo celebrations at Madison Square Garden. The Day of the Dead, the Virgin of Guadalupe celebration, Christmas posadas, and Mexican art and craft exhibits are becoming an integral part of the New York landscape.

It has been sixty years since Puebla’s Miss Maurilia first caught sight of the Statue of Liberty. New York has been coming home to Puebla for years; now, amidst a proliferation of taco trucks and flower venders, Puebla has come home to New York.

Fall 2001, Volume I, Number 1

Santiago Creuheras was the Internship Program Coordinator at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies. Santiago earned a Master of Liberal Arts in Government, a Master of Liberal Arts in History, and the Graduate Certificate for Special Studies in Administration and Management with a concentration in Policy, Planning, and Operations from Harvard University.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Mexico in Transition

You are holding in your hands the first issue of ReVista, formerly known as DRCLAS NEWS.

Over the last couple of years, DRCLAS NEWS has examined different Latin American themes in depth.

The View from Los Angeles

In 1999, on returning home to LA after four years at Harvard and in the Boston area,I ascended to the city of Angels for the annual gala dinner of the premier civil rights firm: the Mexican American…

What’s New about the “New” Mexico

On July 2, 2000, Mexican voters brought to an end seven decades of one-party authoritarian rule. Just over a year later, Mexico continues to feel the repercussions of this momentous victory…