Three Tall Buildings

Viewing Rogelio Salmona

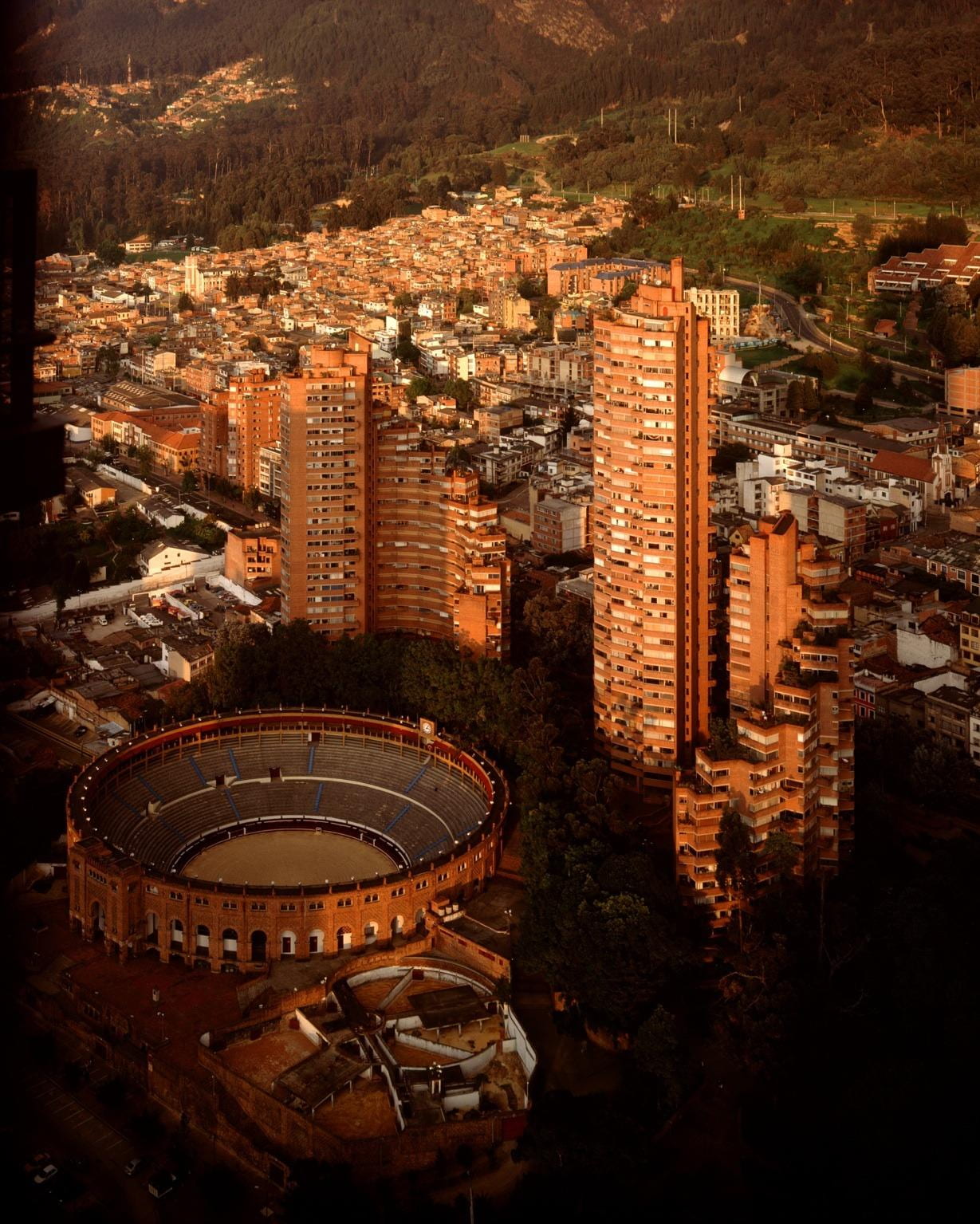

I used to hate the three tall towers that thrust against the verdant mountains.

I used to think that the red brick towers dug into the landscape, belonging to some other city and some other space, created a scar of modernity.

That was thirty years ago. I don’t think my taste in architecture has changed that much, but my relationship to the Torres del Parque certainly has.

For one thing, I can now see the towers from my wide windows across the Parque de Independencia. They do not invade the green view; they blend with it. Perhaps the brick has faded over the years, or more likely the fact is that Bogotá is now a city of apartment buildings. My friends grew up in houses; their children are being raised in elevator buildings with doormen.

The few times that I went to the Torres in the mid-70s and 80s, I approached the buildings in taxi, riding up in the elevator to play Scrabble with a friend. The view in his apartment was of the bullring, and had me thinking that the towers weren’t all that bad from inside. Yet I still disliked them.

Now I live in a historical 1962 building called the Embajador right on the Séptima and gaze up at the towers. Lots of friends live there; the avenue up from the Torres has become a gastronomic paradise, with Mexican, Arab, Cuban, costeño, and even a gringo restaurant called the Hamburguesería; my dry cleaners is in the Torres complex, and so is a fragrant bakery with excellent tinto—the Colombian equivalent of espresso. A coffeehouse-bookstore is right across the street, and so is a video place that rents art films. Needless to say, I walk frequently up through the Parque de Independencia and wend my way through the Torres to this Bogotá version of Greenwich Village.

The steep red brick steps still manage to take the wind out of me. But I often encounter friends with their babies and acquaintances with dogs. I see students and children and old people that seem to have an easier time with the steps than I do, and sometimes I don’t see anyone I know, but lots of people with a vaguely intellectual air that look as if I should know them.

When I look out of my window, I also see the Museum of Modern Art, a squat red brick building that is at once friendly and ugly. After arriving in August, I soon learned Rogelio Salmona was the architect of both the museum and the towers. I should have guessed that because of his signature use of red brick, but then again Bogotá is filled with red brick. So when the museum hosted an exhibit of Salmona’s work, I went in spite of my fairly low expectations: probably lots of photos and architectual mockups.

Children and their parents were ducking under some huge Japanese-like lampshades. Each revolving lampshade bore the name of a Salmona project. I held my breath and ducked. I found myself inside a familiar landscape, the steps leading up to the towers, a space with dogs and kids and folks with shopping bags, a community space. It was no accident that I had hated the towers before, and now enjoyed them as a social space. Salmona hadn’t conceived them just to be glimpsed from a distance, but to be experienced.

The Salmona exhibit was the most interactive I’ve seen in Colombia. Children sprawled on the floor, drawing copies of the building. A teenager was reading an essay on architecture to a group of classmates. Museum-goers watched Salmona explain his architecture on a flat digital television screen, and films flashed overhead. There were indeed the photos and the architectural mockups I had expected, but the explanations gave them context.

I paused in front of one explanatory sign: “Rogelio Salmona’s innovative proposals seek to construct a more democratic city, providing public spaces for living together that gives incentives to sociability, mutual recognition and social organization.”

Salmona’s work, influenced by French architect Le Corbusier, was a response to the migration to Bogotá in the 1950s, I learned from one of the signs. His buildings—many of them so-called social housing—sought to confront marginality, unemployment and housing shortages. His buildings, whether public or private, for the rich or the poor, were surrounded by trees and parks and walkways. Written explanations informed me that some of the parks designed for social housing were never built. None of the signs explained what I remember from Colombian history: heavy migration to Bogotá was caused by people fleeing from La Violencia, the bloody war between liberals and conservatives that wracked Colombia’s countryside. At home, I’m reading a book of journalistic reminiscences by Carlos Villar Borda. Just last night, I was reading his description of the cortes, the intricate machete slashes used by one political band against the other, about the way fetuses were carved out of mother’s wombs and replaced with the head of a cow.

This is what the rural population was fleeing, and this is the city that Salmona wanted to construct to combat those memories. And here I stumble on another sign: “The architecturally-designed building is a place of encounter, to love and to rest, to discover and to experience the passing of time.”

I had come to the exhibit to learn a bit more about my neighboring buildings. I had come to the exhibit perhaps to take a break from thinking about journalism and journalism education and elections and wars and nightmares. And even though the word “violence” was never once mentioned in the exhibit, what I had found was an antidote to violence, the creation of public space and a communal identity.

The kids were still sprawled on the floor, drawing buildings and coloring them, as I left the museum. I glanced up. There were the towers, strong and stable against the glowing mountains.

I love the three tall towers.

See a video of the author discussing her book, A Gringa in Bogotá: Living Colombia’s Invisible War at the Harvard Bookstore by clicking here.

Spring | Summer 2010, Volume IX, Number 2

June Carolyn Erlick is the editor-in-chief of ReVista, the Harvard Review of Latin America. This chapter is reprinted from A Gringa in Bogotá: Living Colombia’s Invisible War by June Carolyn Erlick, Copyright © 2010. Courtesy of the University of Texas Press. Erlick is also the author of Disappeared, A Journalist Silenced (Seal Press, 2004).

Related Articles

Architecture: Editor’s Letter

For years, readers have been commenting on the printed edition of ReVista: “How beautiful!” Now here’s a website to match, thanks to the efforts of the design firm 2communiqué and Kit Barron of DRCLAS. It’s not only a question of reflecting the aesthetics of the printed…

Working in the Antipodes

I was asked by ReVista to write an article on my own work, specifically about the fact that I do simultaneous work on social housing and high-profile architectural projects, something that is, to…

A Tale of Three Buildings

Greek columns, in Thomas Jefferson’s designs for the University of Virginia, might evoke democracy. In Albert Speer’s designs for Berlin during the Third Reich, similar columns serve to…