Towards a National Value Proposition

A Strategy for Competitiveness

Peru has been one of the most remarkable economic growth stories of the last decade, both compared to its own historic record and to its peers in Latin America and beyond. A combination of sound macroeconomic policies since the mid-1990s and a benevolent international economic environment with growing demand for Peru’s natural resources has allowed the country to prosper. Earlier improvements in basic security and political stability had provided an important pre-condition for these achievements.

Underneath this very real success, however, the Peruvian economy is facing a number of significant challenges. First, the lack of diversification and resultant dependence on global commodity markets for natural resources is exposing Peru to high levels of volatility. This has direct costs in terms of prosperity if global resource demand weakens, but it also has indirect costs in terms of long-term investment opportunities lost due to the high level of long-term macroeconomic uncertainty. Second, the impact of the solid growth in headline GDP has been highly varied across different segments of society and different parts of the country. This is a concern from the perspective of the ultimate objectives of economic policy. It is also a threat to political stability, which could eventually undermine the achievements made on macroeconomic and natural resource policy. Third, there are no significant and compelling new growth drivers.

The Need for a Strategy

Peru needs a new competitiveness strategy to address these challenges. The goal must be to achieve prosperity that is broadly shared, not just for the upper income and middle classes. The strategy must provide an overall plan for upgrading, not just a wish list of policy enhancement. And it must lay out a comprehensive vision for the country’s economic future that reflects Peru’s opportunities in the regional and global economy.

The core of a successful economic strategy is to define a national value proposition. This sets forth a distinctive position of Peru given its location, legacy, existing strengths, and potential strengths. The national value proposition defines what is unique about Peru as a business location, and for which type of clusters and other activities does the country offer a strong platform for competitiveness. This national value proposition defines the role that Peru will have with its neighbors, the broader region and the global economy. It identifies Peru’s areas of unique strength relative to peers/neighbors, as well as highlighting the areas where Peru must progress to achieve and maintain parity with peers. And importantly, a national value proposition must set priorities and a sequencing of economic development policies and programs.

The national value proposition should inspire citizens, while committing to companies at home and abroad about what they can expect from Peru. And, it should also guide policymakers in Peru about the most critical priorities in driving Peru’s competitiveness forward.

A National Strategy for Peru

With these goals in mind, we led an inclusive process in 2010 to develop a national value proposition for Peru as well as an accompanying economic strategy. This was to be presented to all the presidential candidates in a CADE event in Urubamba, in the Sacred Valley, before the 2011 elections. The project was financed by the private sector, and involved more than 100 Peruvian experts in twelve thematic working groups. Numerous public sector, business and labor leaders also participated. The team worked closely with all the presidential campaign teams to ensure their awareness and understanding of the effort.

The strategy developed is just as relevant and important today as it was in 2010. Even more so.

The process identified the set of dimensions on which Peru is unique in terms of inherited endowments, business environment, and culture. In terms of endowments, Peru is centrally located in South America, with vast biodiversity and varied ecosystems, as well as abundant natural resources. Peru’s business environment is uniquely open relative to the region in terms of FDI and capital flows, with privileged access to foreign markets due to a series of free trade agreements. Peru has a rich culture and history, a creative and entrepreneurial population that is also young and hardworking, and a legacy of domestic cooperation to overcome obstacles.

Given this analysis and Peru’s other circumstances, the research revealed four interconnected themes that could form the core of Peru’s value proposition: first, Peru has the potential to be the most secure, neutral, rules-based and peaceful location for business in its broader region; second, Peru is the most open economy in the region that can be a hub for trade between Latin America, Asia and North America; third, Peru’s economy has a solid base of dynamic regional industry clusters (geographic concentration of firms and institutions in particular fields) that can potentially drive productivity and growth; and fourth, Peru has the potential to substantially enhance the sophistication and productivity with which it utilizes its substantial natural resource base.

These four themes create the core of a strategic agenda for Peru.

Secure, Neutral, and Peaceful Country

Peru has made tremendous progress in the last two decades in ending a terrorist war and controlling drug trafficking, which have been crucial to unleashing economic growth. Now, the country needs to make sure that these improvements become permanent, to avoid the problems experienced in countries such as Mexico and Colombia. Peru’s continuing security issues include illegal drug trafficking, terrorism, public safety, crime and social instability. These challenges will need to be tackled aggressively if Peru is to continue prosperity growth.

To fight drug trafficking, a comprehensive multi-faceted effort is needed that includes market-based crop-substitution programs, control of chemical inputs for coca processing, and interdiction of drugs and money laundering. These policies should be centralized in a strong institution that coordinates the fight against drug trafficking and terrorist activities. Local residents also need to be mobilized to be part of the eradication process.

Another critical requirement for achieving this theme is absence of corruption. Corruption not only increases the cost of doing business, but is undermining the country’s ability to take advantage of the opportunities it has created through its open trade policy. Corruption also makes improving all parts of the business environment much more difficult. Corruption—along with the conditions that foster corruption—not only hinders international trade and investment but stifles domestic economic activity. It is one of the root causes of Peru’s large informal economy. Corruption is also deeply anti-social, increasing inequality and hurting the weakest the most. An effective anti-corruption campaign is thus a crucial element of an inclusive growth strategy.

Peru’s track record on corruption compares relatively well to many others in the region, but still falls well short of leading countries like Chile, Uruguay or Costa Rica.

Peru will require a systematic campaign to reduce corruption, supported with strong rules and adequate resources. The experience of other countries suggests that a narrow anti-corruption prosecution strategy is not enough. In addition, new rules and regulations are needed to simplify dealing with government and increase transparency to reduce the incentives and opportunities for corruption. Also, the civil service must become a meritocracy, with well-trained, appropriately compensated professionals subject to accountability. Public officials involved in regulation and other key institutions need to be appointed based on independent screening and subject to congressional consent, with strong requirements for transparency and disclosure.

Regional Trade Hub

Peru’s ambitious policy of negotiating free trade agreements with a large number of countries around the world has given it an edge in its quest to become the region’s trading hub. It now needs to deepen this policy and combine it with efforts to eliminate remaining domestic barriers to trade and investment such as tariffs, non-tariff measures and export subsidies. Simplification of customs procedures would take further advantage of trade opportunities.

In a region consumed by ideological debates about the benefits of international integration, Peru could become the springboard for South American firms seeking access to U.S. and Asian markets. Peru needs to foster closer relations with its neighbors and coordinate economic development policies across borders.

To become a real trade power, Peru needs to upgrade its physical infrastructure for transportation, communications and utilities such as energy and water. Peru’s progress in these areas has been largely limited to the locations where economic activity involving natural resources is taking place.

Peru needs significant improvements in its transportation infrastructure to connect isolated regions and to reduce logistical costs. The government’s infrastructure investment program must give highest priority to investments that will increase foreign trade and the competitiveness of the country: those will generate economic growth and prosperity.

Peru also needs an integrated energy policy that provides for supply security combined with environmental sustainability. Energy policy should be oriented toward using the country’s own energy resources, developing energy-related technology and addressing concerns for the global environment.

Peru also needs a more forward-looking water policy, particularly because some of its extractive and agricultural activities rely on water. Peruvian society must develop a culture that places a high value on water. Water fees should cover at least the operation and maintenance of water systems and promote the efficient use and the protection of water quality. Stronger fines should be imposed on water polluters.

Dynamic Regional Development with Vibrant Clusters

The success of competitiveness ultimately reveals itself in particular industry clusters concentrated in sub-national regions within a country. Peru’s growth aspirations can only be achieved if all regions upgrade their competitiveness. In Peru, development remains highly varied across different parts of the country. Lima still concentrates most of the population and economic activity. Each region of Peru needs a clear strategy in order to build its own particular economy based on local strengths.

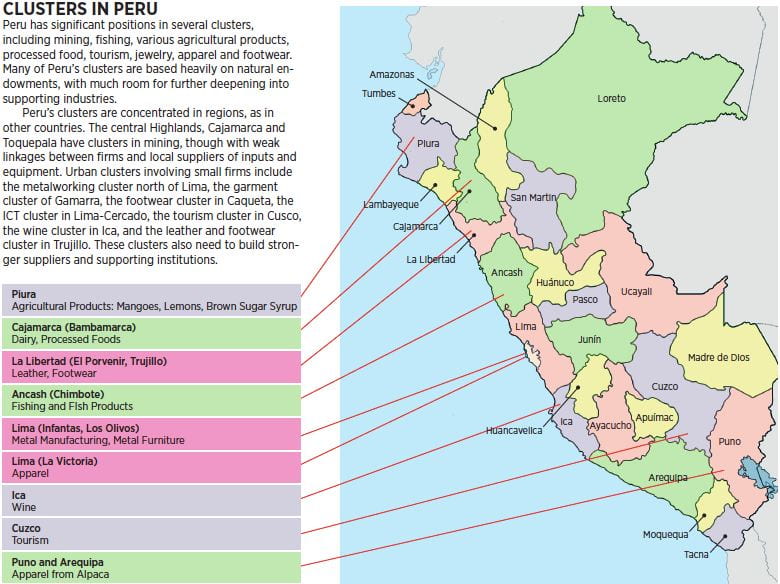

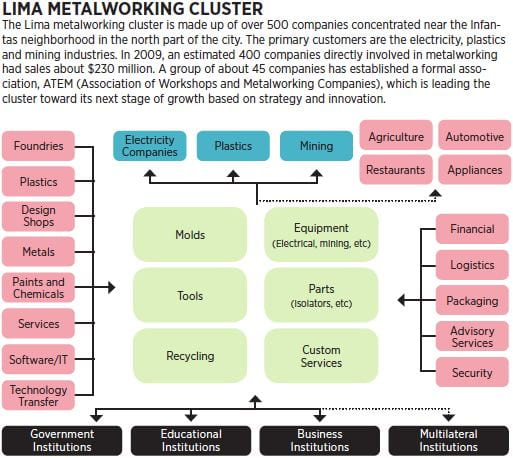

The crucial tool for diversifying the Peruvian economy and fostering regional development is through enabling the formation and development of clusters. Clusters are a geographic concentration of related companies and associated institutions in a particular field, such as the apparel and metalworking clusters in Lima.

Cluster development initiatives engage the private sector and are an effective way to prioritize delivery of social services, develop infrastructure and improve the microeconomic conditions to foment competitiveness at the local level.

In addition to enabling clusters, policies are needed in each region to improve the overall business environments. Decentralization and greater local accountability are the best means to address the social and economic inequality between highland and coastal regions. Peru should build a strong network of regional organizations to channel citizen engagement in economic development planning, thus continuing the process of decentralization. Regions need to improve managerial capacity through establishing a pool of highly qualified civil service professionals able to carry out the technical challenge of managing the resources of the region, and providing technical support for political decisions.

Municipalities in Peru also need to improve tax revenue collection. The national government should also reduce the horizontal imbalances generated by mining royalties (canon minero). The mining royalty system should be re-evaluated so that the income generated by this tax can partly benefit the country as a whole, taking into account the economic development priorities of each region.

Education and technical skills will be crucial supporting factors for higher productivity. They are, unfortunately, areas in which Peru has been lagging. While education alone is not sufficient to jumpstart domestic economic development, its absence has significant negative effects: companies have few incentives to upgrade worker jobs if they have no educated employees to draw on. Unskilled employees and the companies for whom they work find it less advantageous to become part of the formal economy.

Peru must thoroughly reform its educational system, increasing expenditures in public education and prioritizing the improvement of its secondary education system. Dropout rates should be reduced through educational offerings that combine regular education with technical training. Teacher training needs to be based on performance test results, clear and rigorous standards for teaching, and a merit-based professional hiring system.

Aligning workforce training programs to the needs of the private sector in each region will help to narrow the mismatch between educational programs and labor market needs. A workforce strategy based on clusters will help to match curriculums to projected private sector demand. Additionally, revamping the English curriculum with the objective of reaching proficiency by high school graduation would generate a pool of bilingual technicians and professionals needed by companies to connect with global markets.

Coverage and quality of higher education should be improved with both supply and demand-side policies. Financial aid (loans and scholarships) must be available to students from lower income families. Investments should be made in infrastructure facilities and equipment in line with a more demanding university curriculum. University professors should receive incentives to obtain doctoral degrees from leading universities abroad.

Enhancing the Productivity of Natural Resource Utilization

Peru enjoys abundant natural endowments in agriculture, mining, as well as in cultural and natural assets for tourism. In almost all of these areas, however, Peru’s position is largely limited to extraction or, in the case of tourism, limited volume of visitors and low spending per tourist per day. Peru’s natural endowments and cultural assets for tourism could be producing much more economic benefit for the country.

Peru should launch an ambitious program to transform its natural endowment related industries into clusters. This formation of clusters would involve strengthening local supplier capability and increasing the level of collaboration among the companies and institutions together with government.

At a broader level, clusters based on natural resources set the stage for diversification into related clusters. The metalworking cluster of Arequipa, for example, is a result of the dynamism of the mining cluster. Each of Peru’s principal clusters will have its own set of related clusters that draw on similar assets and capabilities. These related clusters provide the best opportunity for Peru to diversify. For instance, the logistical needs critical for mining, agriculture and tourism can give rise to a world class transportation and logistics cluster.

The Peruvian healthcare system needs to be systematically reformed towards increasing coverage and providing better value. Peru needs to improve the effectiveness of the government, reduce labor market regulations, and systematically simplify the rules and regulations for doing business. It should also develop a plan for the long-term deepening of its financial sector, and systematically strengthen its innovation infrastructure. Finally, Peru needs to continue the sound macroeconomic management that has characterized its performance during last decade with prudent fiscal and monetary programs.

Looking Ahead

Peru has come a long way towards becoming a more prosperous economy and society. It has many assets and has already made important policy improvements towards a better future. The results achieved over the past few years are a clear validation of this course.

But Peru also has much more to do. Many parts of society and regions of the country have not been able to fully participate in the country’s recent growth. Many dimensions of competitiveness remain weak and need systematic improvement. The national strategy outlined here provides an ambitious but realistic path forward. It would help define clear priorities, identify concrete action areas, and set measurable objectives.

Ultimately, change occurs only if consensus builds within a country that such change is desirable. Peru’s leaders must come together to ensure that such consensus occurs, and that the inclusive economic vision is above politics.

Michael E. Porter is the Bishop William Lawrence University Professor and Director of the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness, Harvard Business School.

Jorge Ramírez Vallejo is Professor at the University of los Andes in Bogotá, Colombia, and Principal Associate, Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness, Harvard Business School.

This article is based on an unpublished report by Michael E. Porter, Jorge Ramírez-Vallejo, Adolfo Chiri and Christian Ketels, 2011, “Peru: A Strategy for Sustaining Growth and Prosperity.”

Related Articles

The Violence of the VIP Boxes

English + Español

In Peru, the upper class does not like to mix with those they consider different or inferior. Their maids on the beaches south of Lima are not allowed to swim in club pools and, sometimes, not even in the ocean. The VIP boxes at sports and theater events maintained by the government are a public display of a private practice that reproduces in the public sphere the worst aspect of private hierarchical structuring.

Peace and Reconciliation

English + Español

Eleven years have gone by since the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission presented its final report. The report reconstructed the history of many cases of massacres, tortures, murders and other serious crimes. At the same time, it contributed an interpretation of the…

I Ask for Justice: Maya Women, Dictators, and Crime in Guatemala, 1898–1944

On May 10, 2013, General Efraín Ríos Montt sat before a packed courtroom in Guatemala City listening to a three-judge panel convict him of genocide and crimes against humanity. The conviction, which mandated an 80-year prison sentence for the octogenarian, followed five weeks of hearings that included testimony by more than 90 survivors from the Ixil region of the department of El Quiché, experts from a range of academic fields, and military officials.