Transforming Schools Through Art

From Boston to Argentina

Boston ArtS Academy exhibits student talent.

Watching Alberto, a 17-year-old student at the Boston Arts Academy (BAA), at work in the art studio is like witnessing a birth. English is not Alberto’s first language. No one in his family has ever gone to college. Although he is in the 11th grade, he reads only at a third- or fourth-grade level in English. But Alberto not his real name is an outstanding artist. The images he captures using paint, pen, clay, and even photographic film transport viewers to other places, different times. His work is breathtaking.

His gift for art, and the opportunity our school where I am headmaster offers him to develop and refine that gift, has given him the confidence to push forward in a much more painful arena. Alberto wants to be literate.

The Boston Arts Academy was designed as an environment where young people like Alberto can succeed not just as artists, but in academics as well. Students are admitted by audition in music, visual art, dance, or theatre without regard to their previous academic record. They need not have had years of lessons; they are judged on their potential the passion behind their eyes. This is our challenge: to take such students and produce graduates who are both artists and scholars.

Focusing on the arts gives us a unique advantage to achieve this goal. Art pushes us to change the status quo. It forces us to look at the world and at ourselves from different points of view. The usual notion of teacher as expert and student as blank slate works poorly in the arts classroom. In the studio, students achieve best when teachers are coaches, not pedants.

Rigorous study of the arts adds a human dimension to education. When we think and teach about line, color, contrast, value, or rhythm within a social context and ask about the artist and society, we transform the classroom. Why do we find a piece of art beautiful? What is beautiful about impressionist painting or ballet or African masks? What is the culture and history that surrounded that piece of art? Who creates art and why? What are the social purposes, if any, of art? These questions become uniquely captivating for all students. As we pursue them we begin to empower ourselves to change our schools.

How well have we done? Our first seniors will graduate in June 2001, so we are just beginning to see the results. My intuition and experience tell me that our students are flourishing as artists and growing as scholars far beyond what they had thought possible for themselves. Of our 50 seniors, fewer than half, I believe, would be graduating this year from a traditional high school.

Our labors have also borne fruit in an entirely unexpected way. Last year educators from Argentina and Brazil visited the school. They were struck by our efforts to empower our students to “own the word,” as the great Brazilian educator Paolo Freire put it. Talking to our students, they saw the “light behind the eyes.” They sensed the BAA students passion for practicing their art and their love of being in a school that respected that passion.

Would it be possible to start a Boston Arts Academy elsewhere? Were some of our educational practices exportable? Last August a BAA colleague and I went to Argentina, visited schools, and met with teachers, principals, educational leaders, politicians, leaders of NGOs, artists, university professors, and bankers. We went not as experts, with the answers for their educational woes, but rather as colleagues who have worked in an educational landscape also littered with problems and have made significant progress. We discovered that our work at the Boston Arts Academy was absolutely transferable. We found tremendous interest in our ideas for creating educational success for students previously deemed uneducable.

This nascent collaboration has spurred the philanthropic foundation of BankBoston of Argentina, as well as other foundations, to increase their work in education. We return to South America in February to speak at an education conference that BankBoston, FleetBoston, and others are organizing to inaugurate the Boston Arts Academy project in Argentina. We hope to invigorate and inspire a group of educators from five urban and rural schools to radically rethink their ways of teaching and learning. Indeed, we are merely resurrecting Freire’s philosophy, finding ways for students in both our countries to “own their own words.”

When we deny young people the opportunity to experience the arts and humanities, we deny them a basic education. Without such an education, how can they be expected to participate fully in a democratic society? Many aspects of Argentine society are in need of reform. We found our Argentine friends willing to ask the hard questions necessary to begin changing educational systems and structures, and for that reason I am truly hopeful.

Winter/Spring 2001

Linda Nathan is the headmaster of Boston Arts Academy and holds a doctorate from the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Related Articles

Guatemala Diary

In a deeply personal way, I feel like I am home again. Of all the places I have visited, Guatemala is the country I love and feel closest to. Certainly the most impressive aspect is the persevering Mayan people, who endured a 30-year civil war…

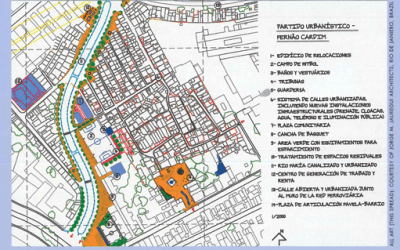

From Favela to Bairro

The Brazilian firm of Jorge Mario J¡uregui Architects is the first Latin American recipient of the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Veronica Rudge Green Award in Urban Design. The award…

Exploring New Horizons in Latin American Contemporary Art

When I first traveled to Peru by boat with my family fifty years ago, the country seemed as far away from Argentina as Boston from Buenos Aires. My husband had been sent there by W.R…