Two Paths to Development

Distinct but Convergent?

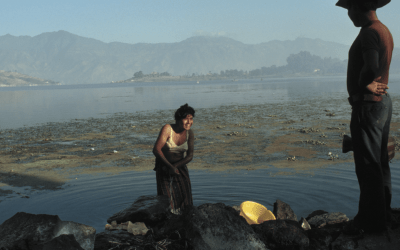

Some twenty miles down a rough cobblestone path through the forests of rural Guatemala, visitors like myself will find a community-based organization (CBO) called Sindicato de Trabajadores Independientes de la Finca Alianza, El Palmar (STIAP). Its self-constructed office is equipped with internet and displays development awards for achievements from alternative energy to coffee exports. Another CBO, the Comité Prosolar Sector Sibinal (CPSS), lies 125 miles in another direction, tucked in the small village of Sipacapa, San Marcos. What this small community has accomplished became evident to me only after carefully listening to the stories of the CBO members.

Both CBOs, operating in impoverished remote areas, have taken on projects in environmental sustainability such as reforestation and production and management of alternative energy. Each has traversed a distinct path. But despite distinctions, could it be that their paths are parallel, even convergent? I recently had the opportunity to take a firsthand look at the routes these two organizations took to arrive where they are now.

Did these two CBOs start from the same point? Defining ‘point’ as ‘capability’ in the development context coined by Harvard economist Amartya Sen, STIAP and CPSS seem to have started from unequal positions in preparing for the projects they intended to accomplish. STIAP’s leadership exudes practical hands-on knowledge that suggests expertise in getting things done. Projects blossom across their land while new ideas ripen in the minds of its able leaders. CPSS’ guiding members don’t have the same directional drive. The difference is in education, past and current alike.

STIAP had the foresight to build a school within its finca and shape its educational curriculum. Children have access to both formal teaching and trade skills such as production of hydroelectric energy, recycling of fuels and hotel administration. This dual track system has produced a cadre of highly educated and focused youth who will someday succeed the current leaders of STIAP. The syndicate’s proven system is transferred to the next generation over the course of years, even decades, by working together on an array of projects.

At CPSS, by contrast, children must walk a considerable distance to reach the school where they are taught reading and writing. While CPSS adults (including the CBO leadership) do have some background in trades, most of them lack elementary skills of reading and writing, a distinct disadvantage for the community.

Yet not long ago, these two organizations found themselves in similar circumstances. The current success of STIAP, an organization which to my untrained eye seemed to have no trouble in turning sustainable development ideas into realized projects, is in fact the product of an entire generation tested by bank struggles and economic strife. Sitting down with Javier Amado, the syndicate manager, I learned how the organization faced, and managed to overcome, the obstacles in its path.

Amado explained how STIAP members averted seizure of their land in 2002 by a Panamanian bank to which they were temporarily indebted. The next year, they established contact with Fondo de Tierras, a state-run organization that agreed to act as a mediator, helping them through credit negotiations, and subsequently becoming their angel creditor. In a fortunate turn of events, the Panamanian bank went bankrupt and relinquished the land claim to the Banco Industrial de Guatemala, which, in collaboration with Fondo de Tierras, returned the land rights to STIAP.

A month later, STIAP signed a Memorandum of Agreement with The Small Grants Programme (SGP) for a grant of $21,073.65. SGP is funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) as a corporate program, implemented by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) on behalf of the GEF partnership, and executed by the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS). To date, program funding from the GEF totals approximately $401 million, with UNDP and UNOPS collaborating to administer more than 6,800 small grants to local Community Based Organizations.

The grant money was for a project focusing on the production of hydroelectricity to power both the homes of local families and machines used to process the macadamia nuts grown on STIAP’s lush hillside. SGP helped STIAP attain the technical expertise to set up the hydroelectric generator and link it to the local grid. They also helped the women of the community to become the financial managers of the grant funds. Today STIAP is a shining star of GEF’s Small Grants Programme, which currently provides grants of up to $50,000 to community-based organizations seeking to undertake projects in the Global Environment Facility’s focal areas of biodiversity conservation, prevention of land degradation, climate change adaptation, protection of international waters, and reduction of persistent organic pollutants.

Speaking with steady enthusiasm, Amado depicted the syndicate’s history: the acquisition and operation of a biodiesel generator and hydroelectric plant, the water purification plant, coffee and macadamia processing operations and an ecotourism hotel with stunning views. He proudly showed me the syndicate’s awards for export of macadamia and coffee. STIAP earned its impressive array of accolades in large part because of its ability to collect, store, distribute and utilize hydroelectricity. The times when coffee price fluctuations made it impossible for STIAP’s management to pay its workers were almost distant memories.

Today STIAP is a shining star of GEF’s Small Grants Programme, which provides grants of up to $50,000 to community-based organizations seeking to undertake projects in the Global Environment Facility’s focal areas of biodiversity conservation, prevention of land degradation, climate change mitigation, protection of international waters, and elimination of persistent organic pollutants.

Today, SGP is working with CPSS to help their community reach the level of self-sufficiency and expertise displayed by STIAP. Local SGP staff Alejandro Santos and Liseth Martínez spent 12 days assessing the community’s needs, formulating a plan and budget for a project, and training community members to bring CPSS to the stage of project initiation. Working with community leaders who had never considered mapping out a project before commencing, let alone drafting a project proposal, Santos and Martínez provided the leaders with guidance on the best ways to turn vague ideas into a concrete plan.

Following the standard SGP process, CPSS’s project proposal was reviewed and approved by the National Steering Committee, and the CBO signed a Memorandum of Agreement with SGP for $19,098 that would be paid out in smaller disbursements over a one-year period. Their project included training the community’s adults to install a solar panel on each of the community’s 36 mud huts. Solar energy from the panels would be used to power five LED light bulbs per hut, displacing the use of environmentally harmful fuels such as diesel for generating electricity. These solar-powered lights would allow CPSS children to study at home at night after a long day of school and work in the fields. Following the solar panel installation, CPSS members, with the help of SGP, diversified their environmental initiative by reforesting nearly five acres with 8,000 native trees, thus helping to reduce land degradation.

Santos spoke to the group about its priorities for the project in its final phase. He probed group members for ideas on how they would utilize the final grant disbursement to achieve the best possible results in the realm of reforestation and climate change mitigation. When their responses drifted from the central premises, he guided them back on course with helpful suggestions.

The SGP team also addressed the treatment of women in the community. Aware of a history of domestic violence and mistreatment of the women in the community, Santos talked with the group about the importance of gender equality and respect for women, making it clear that abusive practices were unacceptable.

Much work still needed to be done to bring the individual and collective capacities of CPSS to a level at which its members could design and carry out their own projects without SGP’s careful guidance. As we drove away, my colleagues once again emphasized the challenges faced by a largely illiterate leadership and what a triumph it was that such a group is now capable of sustaining fruitful environmental projects. Thinking back to Amartya Sen’s development concept of “capability,” it was clear that the learning tools made accessible by SGP had proved catalytic in shifting CPSS’s vision from one of mere subsistence to one of enriching both the environment and the potential of its youth. Though it is not immediately obvious, CPSS is as much a star of the Small Grants Programme as STIAP. There, people without access to financing, expertise, or training were provided credit and empowered through practical hands-on education.

The projects I visited in the Guatemalan highlands with my colleagues both faced challenges of access to resources and tools for development. And while they both were assisted greatly by SGP, their paths to the present are undoubtedly distinct.

Looking to the future, we anticipate that the youth of STIAP will be the ones to manage the ecotourism hotel and expand the export, hydroelectricity and ecotourism operations of the syndicate. The youth of CPSS will become literate and learn valuable life skills currently foreign to their parents. And sometime in the not-too-distant future, they are likely to manage their own micro-development projects without the need for the outside assistance from which their elders benefited. Despite the clear distinctions between these projects, the transition to the next generation may bring a convergence in its achievement of the exact brand of self-sufficiency that is the aim of SGP’s programs in 123 developing countries worldwide.

Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1

David Daepp is Associate Portfolio Manager with the Small Grants Programme of the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS), where he manages the Latin America & Caribbean portfolio. He holds a B.A. in Economics from the College of the Holy Cross and an M.A. in Development Economics from Fordham University. He has written previously for ReVista as well as Américas magazine (published by the Organization of American States) and The Long Term View (Massachusetts School of Law at Andover). He can be contacted at ddaepp@gmail.com.

Related Articles

Guatemala: Editor’s Letter

The diminutive indigenous woman in her bright embroidered blouse waited proudly for her grandson to receive his engineering degree. His mother, also dressed in a traditional flowery blouse—a huipil, took photos with a top-of-the-line digital camera.

Making of the Modern: An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann

Making of the Modern An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1Related Articles

Increasing the Visibility of Guatemalan Immigrants

Guatemalans have been migrating to the United States in large numbers since the late 1970s, but were not highly visible to the U.S. public as Guatemalans. That changed on May 12, 2008, when agents of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) launched the largest single-site workplace raid against undocumented immigrant workers up to that time. As helicopters circled overhead, ICE agents rounded up and arrested …