The Call of Service

What JFK Wrought

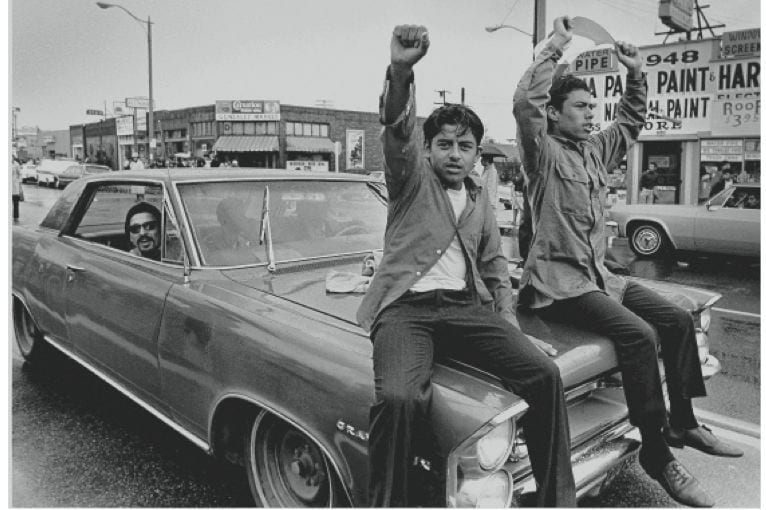

Two young Chicano men ride on the hood of a car during a national Chicano Moratorium Committee march in opposition to the war in Vietnam. Photo by Avid Fenton/Getty

My bellwether, my life-changing day—like that of so many others of my generation—will always be November 22, 1963.

I was a third-grade student sitting in a classroom in the peaceful splendor of the Cherry Lane School in Great Neck, New York, when we heard of the assassination of John F. Kennedy. The very word “assassination”—it was terrifyingly new vocabulary to an eight-year old—summoned the attention of everyone. I acutely remember my teacher’s tears, my family’s grave mood and the general mourning. The President’s death penetrated everything and called for a response, perhaps at first anger but then a kind of penance. At the end of the school year, my teacher told our class that she was joining Peace Corps, the essential institution on which the President had left his mark. She said she was moving for two years to a less privileged place. From that moment, I promised myself that someday so would I.

Simply this explains my subsequent calls to service. My intention, well before I turned ten, was to come to a fuller reckoning with the world that was suddenly revealed to me. With human life apparently unraveling, I somehow felt responsible to help put it back together. I was certain that all of us felt the same way. (I admit to a childlike confusion in trying to understand why we still have failed to do so.) I do not like the tag of “idealism” as my motivator. That implies flight from reality and a sort of aspiration toward transcendence. What moved me was the opposite of that.

Subsequent days in that decade deeply affected our generation’s thinking: April 4, 1968, the killing of Martin Luther King; June 6, 1968, the killing of Bobby Kennedy; October 15, 1969, the day of the nationwide Vietnam moratorium. Their cumulative effect taught us two things: the world is dangerous, and the public action of individuals matters.

From those lessons flowed my own personal commitment. I felt that I had a responsibility to help the afflicted. I had to stand for peace and against needless aggression. I had license to challenge corrupt authority, especially when it existed in my own government.

Children, not only adults, are capable of thinking that way.

Although the end of the days of campus activism preceded my arrival at Harvard College by hardly more than months, I began my studies in 1973 feeling that light years had already passed. That year, the United States ended the military draft. Where the Yard and nearby university buildings had been scenes of unrest and disobedience beginning in April 1969 and lasting for a few years beyond, the only “mass movement” that my class could muster was the new craze of streaking.

Mostly, I retreated with the rest of my peers behind a new normalcy of only apparent peace. The April 1975 surrender of the South Vietnamese to the Vietcong felt like a whimper in Cambridge. To most of us, all the major battles had already been fought.

November 22, 1963, however, continued to resonate for me. I firmly retained the Kennedy-generation goal of pursuing a Peace Corps stint after graduation. Somehow, I quieted my internal debate about how the same government that prosecuted the war in Vietnam would be sending me to another destination in the developing world. The difference of purpose mattered.

After graduation, I accepted a job as a teacher in an elementary school in Manhattan. In April 1978, during spring recess, I took the subway downtown to the Federal Building in New York City to find a Peace Corps placement. I turned many pages in a large loose-leaf notebook until I saw a description seeking “skill-trained” volunteers for Ecuador, skill-trained being shorthand for “unskilled.” I saw that placement as my destiny. Peace Corps invited me to travel to Latin America on July 12. My father, a medical doctor, had aided my application by stating that my recently dislocated shoulder would not be a problem in the field. Years later, I realized the poignancy of my father’s advocacy. For medical reasons, the military had rejected his effort to serve in World War II. I am certain he enjoyed helping me beat the system—a gesture true to our era.

In training in Costa Rica, a dozen or so of us descended upon a series of chicken-coop classrooms in La Guácima near Alajuela. For two and one half months, we learned or improved our Spanish and took classes in cultivating the vegetables and grains that we were to find in our Ecuadorean highland homes. We also learned agricultural-extension techniques so we could transmit of our new knowledge.

There was no denying the oddity of our profile. We were little more than ragged escapees from Ivy League institutions, unsatisfactory marriages, questionable job futures and student loans. We worried, at least among ourselves, about conveying what was at best superficial knowledge to people whose families had been cultivating crops in the Andes since long before recorded history. We were voluntary actors in a peculiarly American tragicomedy about how wanting to do good—in the face of politics, economics and a history that often cried out our shame—was somehow okay.

Ecuador tested our ability to improvise. Were we truly to shake everyone’s hand before sitting in the midst of a meeting with forty or more participants? (Yes.) Was that guinea pig just killed for my lunch because I am truly welcome? (Yes.) Was sitting in the back of a pickup truck full of cilantro the easiest way to travel into town? (For the pleasure of smelling like soup for a week, of course.) I embraced it all, accepting my Ecuadorean neighbors and co-workers as my teachers, while I worked hard to figure out how I could be useful to them. I rebelled against the notion that I, as the tallest, whitest, most novel person for miles around possessed a higher truth than anyone else. With a queer sort of satisfaction, I began to prove my mere humanity to dramatic effect when, on my first Christmas day in Ecuador, I dropped out of a road race not a minute beyond the starting line as I desperately gasped for oxygen running up a gentle slope in the high mountain air.

The 400 inhabitants of El Placer, Cantón Quero, Tungurahua Province, at 10,000 feet above sea level in the Ecuadorean highlands, provided the most effective classroom I have ever had. I learned to value, above all else, interpersonal relationships. I learned to live modestly and to cherish small amenities like a latrine with a curtain, a warm poncho, and potatoes with a sprinkling of salt. We had no electricity; we had no running water in our homes: it was where I wanted to be.

Now nearly 30 years later, I think that regarding my side of the bargain, at least I did them no harm.

For two years, I lived on the second floor of a cinderblock house with a married couple, Selmira Santillán and Gerardo Villacrés—she must have been in her mid-twenties, and he, recently widowed, must have been in his mid-fifties—and their new son, Giovani, born some two weeks after my arrival. At first, something in me was seeking a Thoreauvian idyll. I had every intention to move out of my pre-arranged residence and into a Walden-like self-sufficiency as soon as I had landed there. Mysteriously, however, every time I set out to find a vacant house in the village, neighbors told me the houses were structurally unsound or that the owners were soon to return. I learned months later that I was being closely watched. They would not let me live alone to perpetrate who-knew-what on a suspecting population.

Concerned that my slight knowledge of agricultural practices (combined with a seven-month drought that coincided with my arrival) would do no one much good, I took quickly to visiting the village school, a two-minute walk from my dwelling. By the end of my first year, I managed to convince the three-person faculty and the province’s regional superintendent that I could teach the third grade, using a spare supply room and relieving some crowding from the three classrooms that were uncomfortably integrating six grades.

Without objective measures, I do not think that any teacher can offer a reliable reflection on his students’ achievement. All I can say is that my third graders—previously taught through memorization—became an increasingly animated lot amidst the aura we created together in our snug classroom. We sang and we acted. Together we learned the history of Ecuador and mastered elementary-school writing in Spanish. We figured out the designated science and arithmetic curriculum handed down from Quito.

When the regional superintendent came to visit my classroom the first time, I sensed that he left regretting having bent the national law that prohibited foreigners from teaching in the primary grades. It was early yet. When he returned to evaluate me a few weeks before the school year’s end, my students were jumping from their chairs to answer his questions, certainly in order to demonstrate their knowledge, but also because they were protecting me. In our normally high-wattage classroom, there never had been that level of electricity before.

It fit my understanding of the world’s paradoxes that I was teaching students who were the same age I had been when I decided that one day I would become a Peace Corps volunteer.

Every Monday, my friends Billy, Scott, Meghan and I descended from our various mountainsides into the valley to pick up our mail, shower, and do what most of the rest of the population of Tungurahua was doing: catching up with each other on market day. We easily acquired the habit of exchanging news and recharging our emotional batteries with the people who—no depth of our integration with Ecuadoreans could ever change this—clearly understood each other best. I cherished those relationships, those shared understandings. This was in part because we had developed pride in our mutual sacrifice and so shared something deeper than anything we had felt among our peers as undergraduates.

Sure, we often felt we were walking a fraught Peace Corps tightrope between encouraging dependence and demonstrating our cluelessness. Collectively, however, we came to feel that it was important, while retaining a sense of wonder and good will, to step across socioeconomic, political and cultural borders in order to exchange some knowledge. Thirty years later, I still feel that way.

During the last six months of my stay, I got the bright idea that we might expand our school in El Placer with a new building, and then I learned that the government had in fact long been neglecting a request by the village for an expansion. So I entered, unwittingly at first, into a sort of pyramid scheme. The village council could muster the necessary free labor. I knew some fellow Peace Corps volunteers who thought they could find me a grant in the United States to buy cinder blocks and cement. Counting on those two resources, I knew I could exact a promise from the national government for the contribution of a steel superstructure.

My problems began when I wrongly anticipated the promise of the grant, and, with youthful hubris, I guaranteed the village council that it was forthcoming. Rather than compromise my word, I lied to the government school-building ministry that the labor and the funds were guaranteed, and I entered into a perilous few weeks of hustling for the money to buy materials to complement the structure and labor. Days before my departure, we inaugurated a building nearly complete and built, mostly, on faith and hard labor and an unwillingness to fail.

That life in Peace Corps taught me many lessons that I have carried forth to this day. For fifteen years, I have worked at the (now-Weatherhead) Center for International Affairs at Harvard, an institution, incidentally, twice attacked by student protesters during the Vietnam era, where I feel I am able to exercise my belief in promoting, if not international understanding, an understanding of the international. In volunteer work in my hometown of Concord, I promote community-development projects through a sister-cities relationship with the town of San Marcos, in Nicaragua’s Carazo Department. After the revelations of torture at Abu Ghraib prison, until this last Election Day I led a vigil for peace—and a kind of penance—in Harvard Yard on Wednesdays at noon for four and one half years to protest the violence and murder that our government’s invasion imposed on Iraq.

Along the way, I have tried consistently to exercise my beliefs, whose provenance I trace back 35 years. When working toward change, I try to consult with the people whom the change will most affect. Generative effort matters more to me than the one-time and monumental. I try to understand context—historical, political, economic and spiritual—before presuming to establish new bridges. I am comfortable acknowledging the moral component that underlies my place at work.

If those are legacies of the 1960s, I am proud to try to continue to live them.

Winter 2009, Volume VIII, Number 2

Steven B. Bloomfield is executive director of Harvard’s Weatherhead Center for International Affairs. He lives in Concord, Massachusetts.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: The Sixties

When I first started working on this ReVista issue on Colombia, I thought of dedicating it to the memory of someone who had died. Murdered newspaper editor Guillermo Cano had been my entrée into Colombia when I won an Inter American Press Association fellowship in 1977. Others—journalist Penny Lernoux and photographer Richard Cross—had also committed much of their lives to Colombia, although their untimely deaths were …

The True Impact of the Peace Corps: Returning from the Dominican Republic ’03-’05

I am an RPCV: a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer. For me the Peace Corps was an intense life experience, above anything else. As I continue to reflect on it, I am struck with the many and varied ways in which it continues to affect my life. As a PCV in the Dominican Republic from September 2003 to November 2005, I lived, worked, and learned in a small sugar cane-dependent community two hours outside of Santo Domingo…

In the Shadow of JFK: One Peace Corps Experience

I am often asked about the Peace Corps by students and recent graduates. The most frequent questions are, “why join?”, “what did you do?”, and “what has it meant for your career?” Here is my story. My earliest recollection of international curiosity was in the fourth grade when Sister Margaret Thomas described her experience as a recently returned missionary in Bangladesh. In high school, my sister Mary went to Peru on …