Updates: Harvard’s Latin@ Community

Thirty Years and Counting

Latino life at Harvard. Harvard Crimson.

As a recent Harvard College graduate and active Latin@ student leader, one would think that an article on “the history of the Latin@ community at Harvard” would be a breeze. However, as I quickly realized, an entire tome, much less a short article, could not hope to do justice to the diversity of experiences, opinions and issues that have affected and been championed by Harvard Latin@s over the years.

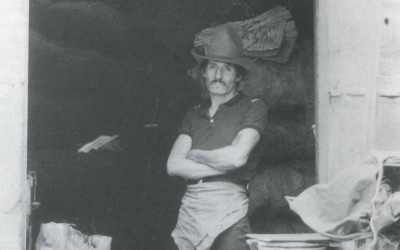

Prior to the civil rights era, most institutions of higher education did not actively recruit students from all economic classes and ethnic backgrounds. It was not until the 1970s that Harvard would see more than one Latin@ student admitted per class. Hugo Morales ’72, J.D. ’75 found himself the only Chicano in the Harvard College 1972 class. He literally did not have contact with a single undergraduate Latin@ student during his first two years of college, although he would actively seek them out, asking random people in Harvard Square whether they were Latin@ or spoke Spanish. A Mixteco Indian from the Mexican state of Oaxaca who came to the United States at the age of nine and lived on a farm labor camp until he came to Harvard, this truly was the greatest culture shock for him, he says. It was not until his junior year, when taking a class taught by then graduate student Rogelio Reyes Ph.D. ‘76 on Boricua/Chican@ history and politics, that he met many of his peers.

Sylvia Balderrama ‘74-‘75, hailing from New Mexico, was the first in her family to even consider going out-of-state for college and came to apply to Radcliffe almost by chance. Accompanying a friend to a recruiting session given by a Seven Sisters representative, Balderrama was caught by surprise when asked her own choice. Not wanting to seem uninformed, she looked down at the brochure she had been given, and quickly blurted out the first name that caught her eye, “Radcliffe.” In a quite incredulous tone of voice, the college representative informed Balderrama that Radcliffe’s application process was rather competitive and that she should apply to other schools as well. Balderrama, feeling compelled to keep to her word, asked her father for the $20 application fee, a significant sum for her family. After mailing in her application, taking the SAT’s in a town 30 miles away, filling out extensive financial aid forms and learning from her principal that Radcliffe had called to ask him whether she “could make it” there, she finally received her letter of admittance. She would soon find that Radcliffe, the only school to which she applied, eagerly awaited her arrival.

Balderrama and Morales recall their time at Harvard University as a series of “first and only” moments. Morales was actively involved in WHRB, the campus radio station, and became the first to host a radio show dedicated to Chican@/Latin@ music. On Saturday nights he would play a wide range of music reflecting his experience, from songs in Spanish to the music of Chican@ rock bands. On Sunday nights, he would bring in members of the Boston Latin@ community (which at the time was mostly Boricua) to play the salsa and merengue tunes that were missing from the airwaves. He became the first undergraduate to have an office at the Kennedy School of Government’s Institute of Politics, and coordinated a speaker series on Chican@ politics, with speakers like organizers Bert Corona and Cesar Chavez.

Although Balderrama found a friendly welcome at Radcliffe, she soon realized the need for extensive student recruitment to render the “first and only” phenomena obsolete. She recalls that the Chican@/Latin@ students at Harvard Law School and the Graduate School of Education had pulled together to create a Boston-wide Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (M.E.Ch.A.) group with students from 20 other universities in the Boston area. Balderrama met other Latin@s in the area, especially when M.E.Ch.A began picketing and passing out flyers on behalf of farm-workers. The connections she made through M.E.Ch.A., especially with married graduate students, helped her adjust to college life through newfound family.

During Balderrama’s freshman year, in 1970-1971, she and 13 other Chican@ students, along with a Boricua freshman that Morales invited, met to discuss the creation of a social support group. Out of these discussions RAZA was born, the first group specifically focused on the culture and issues of the Latin@ students at Harvard. Morales felt that this group should be all-inclusive, because of the limited number of Latin@ students, and suggested the name “Raza Unida.” However, most of the students present vetoed his idea, fearing that he might be trying to create a chapter of a political party of the same name,. Thus, by nature of a sheer majority of its members (and the insistence of some students) RAZA became a support group primarily for Mexican-American students at Harvard College.

The “first and only” generation witnessed many advances for women and people of color, especially within Latin@ organizations. Balderrama cites her senior year when she, along with Morales, were elected the leaders of the Boston chapter of M.E.Ch.A. Not only was she the first undergraduate to be elected to this position, but was the first woman as well.

Fast-forward fifteen years and the Latin@ community was still fighting many of the same battles, albeit in greater numbers and with more diverse backgrounds. David Moguel M.P.P ’90 looks back to his involvement with the Hispanic Caucus (now Latin@ Caucus) at the Kennedy School of Government as one that was focused on initiatives to bring more faculty of color to Harvard University.

Although some classes brought Latin@s at the Law School and School of Education together, there weren’t too many opportunities for undergraduates. New student groups began forming, such as the Cuban American Undergraduate Student Association (CAUSA), Fuerza Quisqueyana (now Fuerza Latina), Latinas Unidas and Concilio Latino. It was the lack of communication and connection opportunities between these student groups that led to the creation of the latter organization.

When Isela Morales ’98, first came to Harvard from Chicago in 1994, “RAZA, Latinas Unidas and Fuerza Quisqueyana (Dominican) were the only active organizations. ‘La O’ (La Organización Borinqueña) had become defunct largely due to the inability of Puerto Ricans from the mainland and the island to get along (as relayed to me by upper-class students). Cuban students, although they did not interact for the most part with the wider Latin@ community, had a somewhat active organization, as well.” She felt at first that as a Puerto Rican student she would not fit in with the members of RAZA. She cites Latinas Unidas as a space where she could meet Latina students of Central and South American backgrounds who often did not feel as comfortable in the established ethnicity-specific groups.

Although Concilio Latino was created in the early 1990’s as the umbrella organization for networking between the Latin@ groups across the university, the Latin@ community was somewhat fragmented and communication between student groups was sporadic at best, according to Armando de la Libertad M.P.P. ’96 (née Ramirez). According to de la Libertad, the Law School’s La Alianza played a key role in hosting social events that connected Latin@s from different schools. Electronic mail promotion of events expanded dramatically from 1994 to 1996. The passage of Proposition 187 in California in November, 1994, proved to be a catalyst that brought the greater Latin@ community together. “Latin@ students at Harvard (and throughout Boston, really) held a candlelight vigil in Harvard Yard,” he recalls. “Students from many states, ethnicities, and nationalities participated in the vigil. It was a time of unity and communal mourning.”

A pivotal event in the history of the Latin@ community at Harvard was the ‘Reunión,’ a conference entitled “A Strategy for the Future: Building a Latino Agenda at Harvard,” organized by Concilio Latino and the Kennedy School of Government at the suggestion of Eddie Duque M.P.P ‘96. Almost a hundred students from across the University attended the 1996 conference, which spawned the creation of five ‘Action Teams’ to develop long-term plans to “mobilize action and build unity” for the Latin@ community at Harvard (Concilio Latino archives). These Action Teams were: Alumni, Communications, Community Outreach, Diversity, and Structure. The idea for Latin@ Welcome Day grew out of these actions teams, and the first was held the Fall after the Reunión. . “You could really see a more cohesive community,” Isela Morales observed. Christopher Tirres M.Div ’97, now a Religion department doctoral candidate, adds, “We are still reaping the benefits of the Reunión: an informal Latin@ alumni group has been created, several Latin@ hires have been made, and the Concilio Latino e-mail listserv has helped to keep us all in better touch with each other’s events.”

A Faculty-sponsored Latin@ Studies Initiative was created due to the realization that the U.S. Latin@ community is becoming an influential presence. With feedback from the Latin@ student community, a conference entitled “Latin@s in the 21st Century: Setting the Research Agenda,” brought together some 50 leading scholars from throughout the country , a historic encounter that will result in an edited volume entitled “Latin@s!” (DRCLAS/UC Press, 2002).

In addition, the persistence and foresight of Nueva Generación members at the Divinity School, among others, have led to advances in diverse faculty hires. A dialogue that began between students and administration at HDS in December 1994 encouraged the recent appointment of Davíd Carrasco to the newly created Neil Rudenstine Chair (see article, p. 58).

Progress has also been made in the scope and variety of Latin@ cultural events students are able to organize. In addition to Latin@ Welcome Day, Concilio Latino has facilitated networking events such as Café Viernes, a community talent showcase, and Latin@ Happy Hour. The Medical Students of Las Americas (MeSLA) organized a Latin@ Heritage extravaganza in conjunction with Concilio Latino’s 1st Annual Latin@ Heritage Month Calendar which prompted Latin@ student groups to organize sooner for the benefit of new members to the community. Comunidad Latina at the Graduate School of Education recently launched their organization’s web-site as an attempt to work past the barrier a one-year Master’s program presents to community-building efforts. The 5th Annual Latin@ Graduation Celebration held on June 7th, 2001, the evening of Commencement, was a tremendous success thanks to the pooling of resources that only the continually developing network of Concilio Latino could provide with relative ease. Support from various Harvard offices and centers, such as the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies (DRCLAS), the Harvard Foundation for Intercultural and Race Relations, and Faculty Diversity and Development programs, have made many of these events possible.

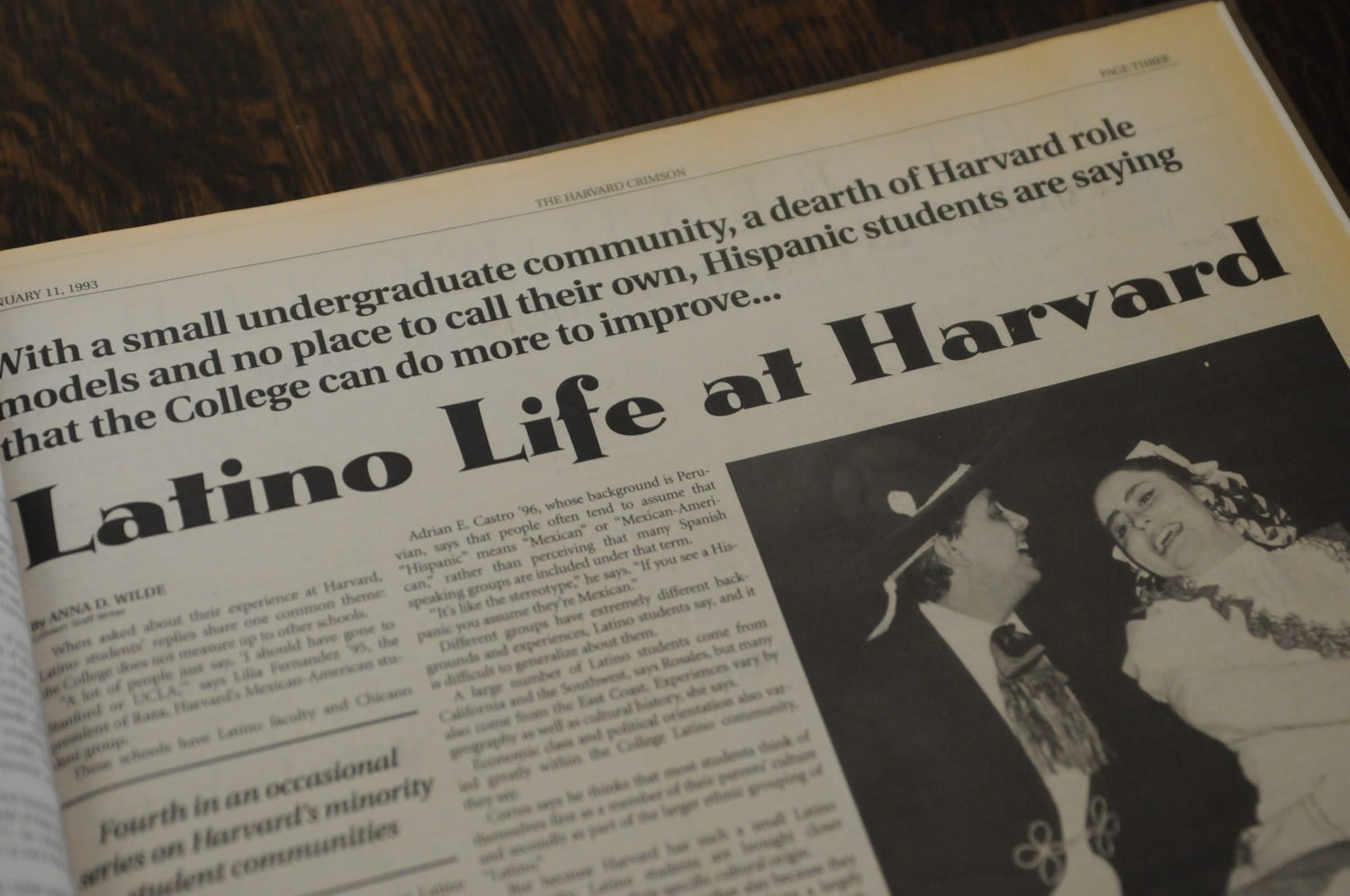

As the Harvard Latin@ community makes its way into the 21st century, we must applaud ourselves for the enormous progress we have made since the days of the “first and only” moments. However, many of the issues that faced the Latin@ community as it first crystallized continue to be of utmost importance. Latin@s may constitute 5% of the student body University-wide, yet this figure has remained stagnant since 1995 (Harvard Factbook, earliest year available) while the United States Latin@ community continues to grow. This reality, in turn, obliges us to work with the University to recruit, admit and retain more Latin@ students at all educational levels. Some advances have been made in Latin@ Studies course offering such as a well-attended “Latino Cultures Seminar” co-taught by Marcelo Suárez-Orozco and Doris Sommer. However, I can personally attest as a Hispanic Studies concentrator who attempted to focus on Latin@s in the U.S., a patchwork of visiting professors and a scarcity of experts in the field make for a frustrating and difficult attempt at innovative and fulfilling scholarship. Harvard needs to achieve the cutting edge in Latin@ Studies scholarship, perhaps finding a model in the strategy used to build the “Dream Team” of the African-American Studies program.

The Harvard Latin@ community, taking many forms over the years, has essentially remained a convergence of students searching for and finding support from others who could empathize with their struggles and appreciate their accomplishments. As in all arenas in life, personal politics and societal factors have occasionally caused us to disagree with each other, but it is imperative that each Harvard Latin@ student stop “fighting for the crumbs.” We must look beyond our personal ideologies and learn to mutually respect and work with each other to increase our share of the pie. As the future leaders of our communities, Harvard Latin@s have the potential to create change and improve the environments where we have developed and grown, both here at Harvard and at home, be it rural California, inner-city Grand Rapids, or the suburbs of Miami.

Fall 2001, Volume I, Number 1

Jeannette Soriano ’01 was Co-Chair of Concilio Latino de Harvard from 1999-2001. She is taking a year off to travel, gain work experience and decide which Harvard graduate school she would like to attend. For more information on the Harvard Latin@ Alumni Mobilization, please contact her at Jeannette_Soriano@post.harvard.edu. Check out Concilio Latino’s website at http://hcs.harvard.edu/~concilio for current information on the Latin@ community at Harvard.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Mexico in Transition

You are holding in your hands the first issue of ReVista, formerly known as DRCLAS NEWS.

Over the last couple of years, DRCLAS NEWS has examined different Latin American themes in depth.

The View from Los Angeles

In 1999, on returning home to LA after four years at Harvard and in the Boston area,I ascended to the city of Angels for the annual gala dinner of the premier civil rights firm: the Mexican American…

What’s New about the “New” Mexico

On July 2, 2000, Mexican voters brought to an end seven decades of one-party authoritarian rule. Just over a year later, Mexico continues to feel the repercussions of this momentous victory…