Viques’ Struggle for Peace

A Lesson Learned for all Puerto Ricans???

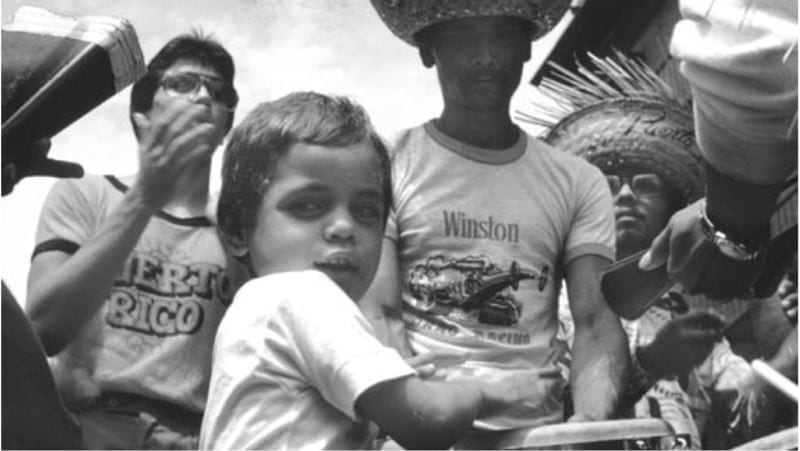

Puerto Ricans express their viewpoints: mainland influence is never far away. Photo by Angel Amy Moreno.

Ever since the Spanish-American War in 1898, the history of relations between the United States and Puerto Rico has been a complex one. Yet the nature of this relationship cries for elucidation because it crucially shapes—stunting or strengthening, your pick—the identity of every Puerto Rican. I have lived my life under such a relationship, personally, experiencing the torn feeling of growing up on an island that has shared for so many years a direct and symbiotic relationship with the United States. Daily, on the radio, on TV, in the newspapers, at work and schools, one listens to the same fruitless political debate between “independentistas (those who favor independence), estadistas (those in favor of statehood), and autonomistas (those in favor of commonwealth status).” And every election year, the status issue controls the main chunk of the political discussion.

What the ubiquity of the issue suggests—and all three main political parties actually do agree on this—is that the relationship, how it is perceived and managed, is an anachronistic one that earnestly calls for a redefinition. The question now is how to guide Puerto Ricans to agree on something they are so strongly and emotionally divided about, or if it is even possible to strike a sustained and productive dialogue between such differing views that could conceivably produce a coherent voice of appeal to the United States. Well, if the struggle for peace in Vieques has proven to Puerto Ricans anything, it is that we should not lose hope, that with a united voice we can in fact effect change. But the caveat is that the civilian population must mobilize and take the reins of the struggle away from political party ideologues. The aim, therefore, is to figure out how and what can unite us as a people in finding that common voice or, at the very least, a clearer one in defining our relationship to the United States.

For those of you unfamiliar with the case of Vieques, it is an island roughly twice the size of Manhattan that lies off the southeastern coast of Puerto Rico and which for the first half of the 20th century had been the economic site of two large sugar companies and the home of about 10,000 US citizens (who from this point forward I will refer to as Viequenses). Yet by 1939, during the incipient stages of the Second World War, the US Navy singled out the island as part of a major defense project for the Caribbean basin. Declaring a national emergency, the Navy quickly expropriated two-thirds of its lands, buying out both sugar companies and relocating the entire civilian population to the heart of the island, uncomfortably squishing them between two military zones.

The relocation was clearly not pleasant for Viequenses. The Navy uprooted them from their homes without offering any type of compensation, placing them on new plots of lands to which they did not even have protected property rights. Because of this, they lived under the constant fear of facing further eviction. But there was not much Puerto Ricans or Viequenses could do about this at the time. During those days, Puerto Rico had passed from the US Department of War (now the Department of Defense) to the power and jurisdiction of the US Department of the Interior, meaning that the U.S. government made most, if not all, of the islands’ decisions. And Puerto Ricans had to endure all of this quietly: nationalists were fiercely persecuted and jailed without evidence and demonstrators had been gunned down in what has become known as the Ponce Massacre. Nevertheless, little anti-American sentiment existed, much less a well-organized anti-U.S. movement that could pose a serious threat to the U.S. government control over the island.

Many Puerto Ricans—and even some Viequenses—strongly believed that a continued association with the United States would improve the dismal economic situation and possibly deliver them out of their misery. Military bases are often known to be economic motors that spur local economies, and there was great hope that this would be the case in Vieques. This, however, never turned out to be the case. For more than 60 years, two-thirds of Vieques’ lands remained empty except for storage, artillery and small arm firing, naval gunfire support, missile shoots, amphibian landing exercises, parachute drops, and submarine maneuvers.

As a result of these practices, Vieques came to be known as the “University of the Seas.” The problem with “Vieques’ University” was that, in contrast to a place like Harvard, its students neither came to stay for a substantial amount of time nor to create a stable community that could consistently stimulate an economy. Marines would merely visit the island to do their practices for a short period of time and leave; they would not settle to commit their lives and money. These visits were sporadic throughout the year, many times purely for a day’s military practice after which they would immediately return to the main island—Puerto Rico. For these same reasons, the Navy’s presence in Vieques did not require a significant steady number of laborers to support its operations. The numbers speak loudly for themselves: the Navy barely employed around 25 Viequense civilians at the bases, while 73% of the approximately 10,000 others remained unemployed.

To survive, many Viequenses turned to fishing and subsistence agriculture. Even today, many Viequenses still live mainly off of these two forms of sustenance. Fishing, especially, has been such a wide practice that it is now an intrinsic part of what it means to be Viequense. The tragic death of David Sanes, a Viequense civilian, during one of the Navy’s military practices on the island in April 1999 served as a catalytic agent for Vieques’ recent peace struggle for civilian control of the island.

Because of the fear of Communism and the theory of containment, the Navy did not return these expropriated lands to civilian control after the end of the war emergency of the 1940s. In fact, Vieques was such an ideal spot for their practices that during the 60s, the Navy even made a concerted effort to remove all civilians from the island. Luís Muñoz Marín, the governor of Puerto Rico at the time, mediated the situation, and President John F. Kennedy intervened, pronouncing an executive order that prevented the Navy from evicting the residents. Nevertheless, the Navy intensified its practices on the two-thirds of the island that it did indeed have in its power. Without needing to pay any permission costs for compensation for the base, as it does in the rest of the world, the Navy took the freedom to advertise Vieques to foreign navies as a place to have military practices using “most non-conventional weapons inventory.” In common language, “most non-conventional weapons” typically means nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons. There have now even been revelations that the Navy went as far as firing depleted uranium munitions in violation of federal law.

Which makes us ask the troubling question about how the Navy was protecting Viequenses, U.S. citizens just as any other, when it did this? The answer is that it simply was not. The Navy contaminated and lived off Vieques by renting it out to foreign navies from which it made yearly profits of approximately $80 million. For more than 60 years, Vieques civilians, basically, had to put up with experiencing daily war conditions. However, for the most part, Viequenses refused to turn this protest into a nationalist issue. The island residents raised their voices to complain against the bleak social and economic conditions they had to bear, rather than concentrate on the unfairness of the US-PR relationship.

For well more than 85 years, Puerto Ricans have been, acquiescently, exemplary U.S. citizens and soldiers. Puerto Ricans have proven to the world that we believe in the tenets of capitalism and democracy; yet, nevertheless, the United States does not seem to have much regard for the island. If it does, how can the U.S. government explain why it allowed this injustice to continue for so long? And when the issue of Vieques became internationally polemical, why did the U.S. government decide to just tolerate the protests and keep on, sanctioning further practices for three more grueling years after Puerto Ricans had already unified in a virtually unprecedented unanimous plea to terminally end these military practices. As Puerto Ricans, we are now ever more ready for the U.S. government to provide us with some answers.

Yet the U.S. government finally saw its hand forced from the perseverant spirit of the civil movement which united across parties with a common penchant for justice in Vieques. If this had not been the case, and Puerto Ricans had left the Vieques issue solely in the hands of political parties instead of uniting into a broad civil coalition, we might have today still found ourselves struggling with the Navy’s presence in Vieques. The sad fact of the Vieques struggle, however, is that it took Puerto Ricans more than 60 years, high cancer rates, and a couple of civilian deaths before it nationally mobilized to stop this. And even today, the fight still continues for the decontamination, devolution and proper development of these lands. The first one, decontamination, is presently the most imperative because it has been confirmed that Vieques has the highest rates of cancer in Puerto Rico—26.7% higher than Puerto Rico’s average.

Puerto Ricans must now avoid turning the Vieques peace movement into simply a bittersweet part of our history books and rather look for it to become a momentous lesson learned that we can apply to other thorny political issues that are facing the island, such as the ever-present status issue. The Vieques peace struggle demonstrated that if Puerto Ricans organize and mobilize across political parties persistently, a civilian grassroots movement has the potential of summoning enough international attention that could twist the U.S. government’s hand hard enough for it to change policy. For the status issue, we must again find that lowest common denominator to which most Puerto Ricans can agree to. Only then will the United States be compelled to pay it its due attention. And only then can we begin hoping for a better Puerto Rico. It is in our hands to embrace the challenge to design it. Que así nos ayude Dios!

Spring/Summer 2005, Volume IV, Number 2

Sebastián J. Sánchez graduated from Harvard College in the class of 2004, where he majored in government. Since then, he has joined the DRCLAS staff full-time. In the near future, he looks forward to continuing his graduate studies. He kindheartedly thanks June Carolyn Erlick and Silvia Álvarez Curbelo for their significant contributions to this article.

Related Articles

Introduction: Bush Administration Policy

So it is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny…

International Symposium in Puebla

It is likely that Don Quijote first reached the Western hemisphere—in what was, at the time, lightning speed—as a stowaway. On September 28, 1605, Franciscan commissioners of the…

Adiós 61 Kirkland

For the past eight years, the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies has made its home at 61 Kirkland Street. Countless film screenings, celebrations and roundtable discussions…