A Review of Wait for Me, True Stories of War, Love and Rock & Roll

Revisiting Central America’s Quagmire

Forty years ago, when traveling to visit family and friends in Europe from conflict zones of Central America, I was often asked: “So, how are things going over there?” Even those who read stories in newspapers rarely express much interest in the answer or curiosity as to what was behind the conflict. And, let me remind you, this was a time when the wars in Nicaragua and El Salvador were hogging media attention, having been denounced by Washington as fearsome threats to U.S. national security. Still, few readers and viewers had much idea of what was happening on the ground.

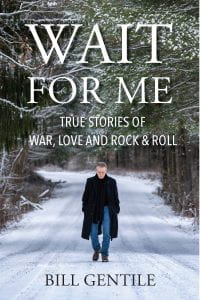

Now, in his vivid memoir, Wait for Me, True Stories of War, Love and Rock & Roll, Bill Gentile turns back the clock to the 1980s and thrusts us into the mountains of Nicaragua and the slums of El Salvador to offer what he calls “a firsthand, frontline account of the human cost of war.” He succeeds for two simple reasons: he was willing to take serious risks and, more pertinently, he survived to tell his story when so many around him—soldiers, rebels and photojournalists like himself—were killed. It was, to put it bluntly, a murderous time.

I was an old hand in Central America by the time Gentile was sent by United Press International (UPI)’s Mexico bureau to help out with reporting the Sandinista revolution that toppled the Somoza dynasty in July 1979. But our lives barely overlapped. After 12 years of watching the region disintegrate, I left for other climes in 1983, the same year that Gentile moved to Nicaragua where he stayed until the Sandinistas were voted out of office in 1990. In other words, our experiences were very different: I covered Nicaragua; he lived it.

Something else rather obvious distinguished Gentile from me and most mainstream correspondents: we were reporting in words. In contrast, whether as a freelance, contract or staff photographer (at different times he was all three), Gentile needed images. In Nicaragua or El Salvador, I could safely ignore some routine clash between soldiers and guerrillas unless it advanced the story. Gentile and his visual media colleagues would rush towards the sound of gunfire because it might just give them the photo that would illustrate the entire war.

Not my idea of fun, but to take that route (and there are myriad photographers still doing so in other wars), it helps to feel the immortality of youth or to be persuaded that, even while taking precautions, a sobering level of risk is required in order to win fame and fortune. As it happens, Gentile also had a secret weapon: before particularly perilous sorties, he would ask his devout great-aunt Carmella to offer up some prayers for him. He needed them and, apparently, they worked.

“None of the Sandinistas, or contras, for that matter, wore bullet-proof vests. Nobody wore helmets or protective goggles. I had absolutely no protective gear. I had no health insurance policy. No death insurance policy. I couldn’t afford them. I didn’t believe in them. I had no ironclad guarantee that, if I got hurt, somebody would come to my rescue,” he tells us.

Looking back, I think danger seemed more palatable because, like Gentile, many U.S. and European reporters gave their assignment the aura of a mission: to denounce the successive evils of the Somoza dictatorship and U.S. imperialism, no ifs or buts. “I had concluded that the story was so important that it was worth the risk,” Gentile writes. “I was convinced that my country’s intervention in these poor, developing countries needed to be addressed and challenged by the institution whose responsibility it was to do so: journalism.”

Stirring words, no doubt, but what if there are no images as evidence? At one point, Gentile spends weeks at the front burning with frustration. “Nice pictures, but where is the war I came to document? To denounce? Is this what Newsweek magazine wants to use in next week’s publication. No. I need the real stuff. I need ‘bang, bang.’ I need war.”

The “need” does raise questions. If war unavoidably means people killing each other, he reflects, “I don’t actually wish for anybody to get hurt, to get killed, but I do wish for some action, and I wish it would come soon, before I’m too wiped out to be able to make pictures of it.” The message is clear: no photo equals no fee and no plaudits. Clearly Gentile was not the first reporter or photographer to become hooked on danger and he doesn’t deny it. “There is nothing like the exhilaration of having survived the near-death experience of combat. Nothing.”

Still, there is more to Wait For Me than Gentile’s regular excursions towards La Montaña and its jungle warfare in his beloved 1969 four-wheel drive International Harvester Scout, which he baptized La Bestia. For one, from early in life his large and ebullient Italian family—both of his parents were born in Italy—gave him love, support and guidance and fed his imagination. His father worked in one of Pennsylvania’s many steel mills and it was also there that Gentile did time during the summer to pay for studying at Penn State University. Life was not cushy, but it also braced him for the struggle of making it in journalism.

“There were no Harvards, Yales or Oxfords in my family. There were no presidents, governors or senators. No doctors or lawyers. No journalists,” he writes. “It was the men who fought and sometimes died in foreign wars who prepared me for the conflict zones” of Central America and, later, other wars.

The many pages that Gentile devotes to growing up underline the continuity of his life: the need to shake off his roots as well as the need to return to them. Leaving for California was a first step. Leaving for Mexico City in 1977 was a bigger step. It led to freelance work for UPI and then a desk job and that first taste of revolution in Nicaragua in 1979. Next came a stretch on the UPI Foreign Desk in New York and then the leap back into freelance work and a return to Managua where, perhaps not coincidentally, a young Sandinista named Claudia awaited him.

Claudia is justly thanked warmly in this book’s acknowledgements because while she and Gentile loved each other, broke up, got married and then divorced, they remain friends. More importantly, it was thanks to Claudia and her extended family that Bill came to understand the inner workings of Nicaraguan society. Conversely, when Claudia’s soldier brother Danilo was badly wounded in a clash with Contra fighters (and became handicapped for life), her family never held it against Gentile that his country’s government was indirectly to blame.

For anyone covering Central America at that time, there was also no way to avoid El Salvador, with some correspondents preferring it to Managua as a base. Gentile would go there on assignment with some trepidation. “I never liked El Salvador,” he writes. “It had extracted too much blood from too many people and too many of its victims were my friends and colleagues.” Among these was John Hoagland, an experienced photographer who had helped Bill learn the trade. “A tiny and overcrowded country, El Salvador had a menacing, sinister feel about it.” That too I remember.

Once the Cold War ended, some degree of peace returned to Central America and Gentile moved on, finding no end of fresh trouble spots to cover, from Peru’s Shining Path war and Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait to the genocide in Rwanda and more, winning two Emmy awards and, thanks to his experience as a documentary-maker as well as a photographer, in 2003 joining the faculty of American University’s School of Communications in Washington DC.

Yet for all his wanderings, it doesn’t surprise me that Nicaragua dominates this book just as it has dominated his life. It did so with love and idealism and action in the 1980s, making possible the career he forged. It has also brought him the pain felt by so many of us who, naively or not, imagined it possible for a youthful rebel army to overthrow a detested dictator and actually lift the country out of centuries-old poverty.

Did it have to be like this—that Nicaragua should again be a dictatorship, this time under the same Daniel Ortega who led the Sandinista revolution in 1979, was defeated in 1990, returned to power in 2006 and, having crushed all opposition, will be seeking his third re-election in November this year?

Gentile returned to Managua two years ago for the 40th anniversary of the revolution and felt only disillusion. “I saw a Nicaragua deeply divided between supporters and opponents of the Sandinista regime,” he writes. “I felt uneasy. Too many people watching me from the corners of their eyes or from behind dark glasses.” The saddest thing is that so many people died thinking things could be different. Gentile’s consolation is that at least he came out of it alive.

Spring/Summer 2021, Volume XX, Number 3

Alan Riding is a former correspondent of The New York Times who covered Mexico and Central America between 1971 and 1983. He is the author of Distant Neighbors: A Portrait of the Mexicans and And The Show Went on: Cultural Life in Nazi-Occupied Paris. He lives in Paris and is now writing for the theater.

Related Articles

A Review of Lula: A People’s President and the Fight for Brazil’s Future

André Pagliarini’s new book arrives at a timely moment. During the summer of 2025, when the book was released, the United States began engaging in deeper debates about Brazil’s political situation. This shift was tied to the U.S. government’s decision to impose 50% tariffs on Brazilian products—the highest level ever applied to another country, matched only by India. In a letter to President Lula, Donald Trump’s administration justified the measure by citing a trade deficit with Brazil. It also criticized the South American nation for prosecuting one of Washington’s ideological allies, former president Jair Bolsonaro, on charges of attempting a coup d’état. Sentenced by Brazil’s Supreme Court to just over 27 years in prison, the right-wing leader had lost his 2022 reelection bid to a well-known leftist figure, Lula da Silva, and now stands, for many, as a global example of how a democracy can respond to those who attack it and attempt to cling to power through force.

A Review of The Archive and the Aural City: Sound, Knowledge, and the Politics of Listening

Alejandro L. Madrid’s new book challenged me, the former organizer of a musical festival in Mexico, to open my mind and entertain new ways to perceive a world where I once lived. In The Archive and the Aural City: Sound, Knowledge, and the Politics of Listening, he introduced me to networks of Mexico City sound archive creators who connect with each other as well as their counterparts throughout Latin America. For me, Mexico was a wonderland of sound and, while I listened to lots of music during the 18 years I explored the country, there was much I did not hear.

A Review of The Interior: Recentering Brazilian History

The focus of The Interior, an edited collection of articles, is to “recenter Brazilian history,” as editors Frederico Freitas and Jacob Blanc establish in the book’s subtitle. Drawing on the multiplicity of meanings of the term “interior” (and its sometimes extension, sometimes counterpart: sertão) in Brazil over time and across the country’s vast inland spaces, the editors put together a collection of texts that span most regions, representing several types of Brazilian interiors.