With Santiago Álvarez, Chronicler of the Third World

An Interview by Luciano Castillo and Manuel. M. Hadad

Santiago Álvarez (1919-1998) brought together the founding group of the Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (ICAIC) in 1959. The following year, he created the Noticiero ICAIC Latinoamericano, imprinting on it his innovative style of cinematic journalism. He headed up ICAIC’s Short Film Department from 1961 to 1967. A filmmaker with international interests, Álvarez traveled to more than 90 countries with his camera. He bequeathed to the history of documentary filmmaking such classics as Now! (1965) – seen by some as the precursor of today’s video-clip – Ciclón (1963),Hanoi, martes 13 (1967), L.B.J. (1968) and 79 primaveras (1969), among many others.

It is worth noting that the predominant stylistic feature in Álvarez’s prolific body of work – which he called “documentalurgia” – is the extraordinarily rhythmical mix of visual and aural forms, drawing from everything at his grasp (historical documentaries, photos, fictional images, animation, signs) with a certain dose of irony and satire to convey his message. Although he utilized fictional elements in his short film El sueño del pongo (1970), his only incursion into a long feature film, Los refugiados de la Cueva del Muerto (1983), fell short of expectations.

An assessment of his filmography leaves no doubt that his first short documentaries prevail by their own merits over his later, longer works. While facing the decline in documentary production in Cuban cinema, the almost octogenarian filmmaker, in a tireless defense of Cine urgente, began experimenting with video as an alternative. Santiago Álvarez – a man who deals in basics and for whom the force of images always stands out – insisted that “documentary film is not a minor genre, as people believe, but rather an attitude towards life, towards injustice, towards beauty, and the best mode for promoting the interests of the Third World.”

Q: Edmundo Aray called his bibliographic compilation of your cinematic oeuvre “Cronista del Tercer Mundo.” What do you think of this title?

A: It is rather broad. Surely Edmundo Aray thought of the Third World, while preparing the book on my work and realizing that over thirty years I have covered places where history has unfolded in a very strong and dramatic fashion. I have been to Vietnam, Kampuchea, Laos, Mozambique, Angola, Ethiopia, to various countries of Latin America such as Mexico, Uruguay, Argentina, Chile; all except Haiti. I have made documentaries in all of them. This may conform to what the work of a chronicler of Third World countries might look like. The work of a cinematographic chronicler is different from that of chroniclers in print and other media, so perhaps it would have occurred to Aray to title the book in this way.

Q: In your vast filmography you have produced a considerable number of classics, but is there some work that you consider your favorite?

A: It is difficult to say, because each moment in my career has had its emotions, its characteristics. To confine myself to one or two is difficult for me, though I like Hanoi, martes 13 for obvious reasons. First because I was there during the first US bombings of Hanoi, and second because the Vietnamese people, the knowledge that these people have, the fifteen times that I have been there – before, during and after the war – have imbued in me a love and passion for Vietnam, for what it has signified over the decades, that it has had to fight against all kinds of imperialism: Chinese feudalism, French colonialism and finally North American imperialism.

In some sense, since I have worked in Vietnam quite a bit – I have made more than a dozen documentaries on this country – it is possible that I am attracted sentimentally by that work that I continue there, aside from the very special characteristics that its people possess. With their hands, feet and mode of fighting against the enemy, they defeated the biggest and most sophisticated imperialism of all. A poor people, semi-naked, shoeless, without the military boots used by the US soldiers to avoid venomous snakes, without the potable water that all the soldiers drank, malaria-ridden, full of parasites, hungry, they fought indefatigably against the aggressor. I feel a special affection for them. The work that I have done in their country has a deep and special place in my heart.

Q: There are three basic elements in your documentary filmmaking: the editing, the music and the graphics. Still, Rebeca Chávez, who was an assistant of yours, characterizes it as “the mystery of intuition.” When you prepare to make a documentary, does it really take shape as a fruit of the imagination?

A: If intuition has to do with magic and mystery, it is probably true. But I don’t think it is really accurate to say that my work is solely intuitive. Without the experience that I have had in my life – if I had not been in the United States, if I had not washed dishes in New York, if I had not been a miner, if I had not been a young rebel fighting against injustice, if I had not worked in the children’s radio hour program when I was 14 and 15 years old because I had a political calling – if I had not done all this, I don’t think intuition would have yielded anything.

Perhaps there is something “mysterious” to intuition, but if the intuitive is not linked to a reality that one has lived, the experience that one has had would not convert itself into something intuitive.

I question the concept of intuition in relation to work because however intuitive you might be, if you do not have a cultural base, an experience of reality, I don’t think intuition would surface. There are those who believe that people are born wise, but nobody is born knowing everything; rather, over time one studies, learns, obtains life experience, reproduces this experience mentally, sentimentally; then, the intuitive emerges. This how I understand “intuition.” If this describes the work that I have done over thirty years as a filmmaker, fine, let us call it “intuitive.”

Q: One of the important stages in your training was working with music in a radio station. Did this experience help you master rhythms in music?

A: Yes, it is a part of my life, a fundamental part. Again, this is why I question this idea of the intuitive. If I had not worked in the music archives in the station CMQ during the time that I did, sorting music that had been bought for radio and television programs, if I had not been trained in classifying the musical feeling to be used, I wouldn’t have realized the capacity of making something with a musical sentiment. Perhaps thanks to the fact that I worked there for years, I developed a kind of musical temperament and learned to use music for given moments of an aesthetic operation.

Having been at CMQ gave me this training, this development of the “musical ear.” I have always liked music. I keep the CDs that they give me; my wife also likes music and helps me a lot in the classification of future musical moments that can be used. So I insist that intuition is very relative, because without this training, I would not have developed this “ear” for using music in a given sequence of a documentary or newsreel.

Q: In the creative process, there are two forms your documentaries have taken: one time like in Mi hermano Fidel, which was an accidental documentary, produced as the fruit of an interview done with Fidel Castro for the long film La guerra necesaria…

A: A sub-product.

Q: Yes, a masterly sub-product, but are there documentaries in which you developed the script before filming, or that you filmed and then later re-developed?

A: I never write scripts. This confession might surprise many people. I don’t use conventional scripts, which many of my colleagues work with or which obliges them to work.

The script in my documentaries is in my head and in my feelings. It is as if I were a human computer with a background of life experiences, and then one time, I pushed a button and produced some cinematic work. I draw on the past to serve as a script in the time to realize a certain work.

For example, Now! is a documentary that was born neither through intuition nor through the mysterious art of a creator. It came to be because I had seen racial discrimination in the United States with my own eyes. When circumstances became favorable for speaking out against discrimination, I already had this experience stored in my brain, and I used it to realizeNow!.

I heard the song Now! when a black leader named Robert Williams gave it to me on a CD during a trip to Cuba. I was his friend. I visited his house and one day he gave me a CD and said: “See how you like this”; and it was the music of Hava Nagila. I asked him: “you’re giving it to me as a gift?” And he gave it to me. After listening to it multiple times, it occurred to me to make a documentary precisely in time with this song.

Logically, I had already come into contact withy racial discrimination in the United States, and when I listened to the music of Now!, I began to retrieve from my musical archives what would later appear in the documentary. There was no script, but rather a whole past that was impressed on my retina and my brain, and when I set out to reject this political situation of racial discrimination, a certain experience re-surfaced. At last I could create my film.

The script is in the song itself. As you follow the song, you write the script. That is what happens in this documentary.

In the case of other documentaries on Vietnam, what script would I make? I did not know what was going to happen. When we arrived, the war was ongoing and the bombings were about to begin. The news on the tremendous aggression of the Yankee empire was terrible. I decided to go to this country to be in solidarity with its people, even though we did not have sufficient equipment; we went with a 16 mm camera and a potpourri of various kinds of films: British, North American, Italian, which had been given to us by the delegations that constantly visited Cuba at the beginning of the Revolution.

With these black and white 16 mm movies from different countries, with cameras that could record no more than three minutes at a time before the roll had to be replaced, without recorders, without lights; I used to take a battery that had been given to me by the Soviets when we passed through Moscow; a battery that looked like a tank and weighed like the devil. We called it the “washbasin” and that is what it looked like: a washbasin for lighting. That was the equipment that we brought to Vietnam.

What script was I going to use? The day after we arrived, the bombing of Hanoi began. We had been notified that the North Americans were going to bomb unprotected cities like the capital at any moment. Under international law, an unprotected city could not be bombed, a city [that] does not intend to invade others or to store military equipment. Nonetheless, this is what happened.

I didn’t know what was going to happen when we were there. I did not think about how I was going to realize the work. On the day we arrived, I began to look for the places where I guessed the bombings might start, such as for example, the bridge over the Red River. I said: “surely this bridge will be a target”; I had this feeling that it was going to be bombed; I began to note the places we were going to film in the imminent bombing of Hanoi. There was no script.

The bombing happened, and we began to look at everything we filmed, to search for additional details to recreate the bombing. It is in the editing room, once one sees all the rushes and analyzes them, that one begins to make a “script,” a potential plan for how to assemble the film.

Moreover, while the title of a documentary has not yet come to me, I cannot begin to assemble it. I need to have the title in order to begin to structure a documentary. The title, for me, comes to be like a cell where all the inherited actions that will give shape to the idea that later becomes a script encounter each other; that is to say, one should take whatever action that one might want to film as a diary: to signal what one believes to be most important on that day. This diary is later converted in the editing room into a kind of primer or script. As long as you don’t have all the developed film, even the rushes, the title, you’re already thinking of the music. In summary: I edit, and I don’t wait like others do to finish editing before putting on the music. Rather, I prepare the music simultaneously. In reality, there is no conventional script.

I believe that the documentary, like a newsreel, is “take one.” The documentary looks a lot like the work of newsreel, which is “take one” as well. This frees you from having to use a script, because you prepare it in the midst of filming things, actions that will help you afterwards to combine everything in editing, to put one image after another. You begin to use the typical language of film, which is the staging.

Q: The exceptional use of the interview as a resource in your work, which contrasts with contemporary documentary film, not only Cuban, where there is an abuse of interviews and scarce cinematic development.

A: Most of my documentaries have neither interviews nor narration; I always try to avoid them. When there is no further remedy left to me, I use them, such as for instance, in La guerra necesaria. I use narration, the speaker, in another style, but I have deliberately done most of my work without oral narration. It is music and the lyrics of the songs that I use as the narrative elements of the documentary. The film in pure state, truly.

Con Santiago Álvarez, Cronista Del Tercer Mundo

Santiago Álvarez (1919-1998) integró el grupo fundador del Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (ICAIC) en 1959. Al año siguiente creó el Noticiero ICAIC Latinoamericano, al que imprimió un estilo particular innovador del periodismo cinematográfico y dirigió el Departamento de Cortometrajes en el período que va de 1961 a 1967. Rigurosamente internacionalista, Santiago Álvarez recorrió con su cámara más de 90 países. Legó a la historia del cine documental clásicos como Now! (1965) —conceptuado por algunos de precursor del actual video-clip—Ciclón (1963), Hanoi, martes 13 (1967), L.B.J. (1968) y 79 primaveras (1969), entre muchos otros.

No es reiterativo señalar que el rasgo estilístico predominante en la prolífica obra de Álvarez —que él llamo documentalurgia— es la mezcla extraordinariamente rítmica de las formas visuales y auditivas al apelar a todo lo que esté a su alcance (metraje documental histórico, fotos fijas, imágenes de ficción, animación, carteles) con cierta dosis de ironía y sátira para trasmitir su mensaje. Aunque apeló a elementos de ficción en su cortometraje El sueño del pongo (1970), su única incursión en el largometraje argumental, Los refugiados de la Cueva del Muerto (1983), quedó muy por debajo de las expectativas.

En un balance de su filmografía es indudable que sus primeros cortometrajes prevalecen por méritos propios sobre las obras posteriores de mayor duración. Ante el descenso de la producción documental en el cine cubano, el casi octogenario cineasta, en su infatigable defensa del Cine urgente, incursionó en el vídeo como alternativa. Santiago Álvarez —hombre fundamental en el que siempre destaca la fuerza de las imágenes— insistió en que “el cine documental no es un género menor, como se cree, sino una actitud ante la vida, ante la injusticia, ante la belleza y la mejor forma de promover los intereses del Tercer Mundo”.

Q: Edmundo Aray llamó Cronista del Tercer Mundo a la compilación bibliográfica que realizó de su que hacer cinematográfico, ¿qué opina sobre esta definición?

A: Es un poco amplia, seguramente Edmundo Aray al preparar el libro sobre mi obra y advertir que he recorrido durante treinta años los lugares donde la historia contemporánea ha sido muy fuerte y muy dramática, pensó en lo del Tercer Mundo. Yo he estado en Vietnam, Kampuchea, Laos, Mozambique, en Angola, Etiopía, en varios países de América Latina como son México, Uruguay, Argentina, Chile; todos excepto Haití. Los he visitado, realizado documentales en todos ellos y es posible que esto conforme una idea del trabajo de uno como cronista de los países del Tercer Mundo.

El trabajo de un cronista cinematográfico; no es el de un cronista de prensa escrita ni de otro medio de comunicación, y a partir de ahí se le habrá ocurrido titular el libro de esa forma.

Q: En su amplia filmografía usted cuenta con una considerable cantidad de clásicos pero, ¿existe algún título que sea el que prefiera?

A: Es difícil responder porque cada circunstancia ha tenido sus emociones, sus características; circunscribirse a uno o dos momentos se me dificulta aunque, por ejemplo, Hanoi, martes 13 a mí me gusta mucho por razones obvias. Primero porque fui protagonista del primer bombardeo a Hanoi por parte de los agresores yanquis, y segundo, porque el pueblo vietnamita, el conocimiento que he tenido de ese pueblo, las quince veces que he estado allí —antes, durante y después de la guerra—, me ha imbuido de un amor y una pasión por Vietnam, por lo que ha significado durante siglos, que ha tenido que estar luchando contra todo tipo de imperialismo: el feudalismo chino, contra al colonialismo francés y por último contra el imperialismo norteamericano.

De cierta manera, como he trabajado bastante, —he realizado más de una docena de documentales sobre ese país—, es posible que me atraiga sentimentalmente ese trabajo continuo allí; aparte de las características muy especiales que tiene su pueblo, que con sus manos, pies y modo de luchar contra el enemigo, venció al más grande de los imperialismos de todas las épocas, al más sofisticado de todos los imperialismos. Un pueblo pobre, semidesnudo, sin zapatos, sin las botas militares con las que evitaban los soldados norteamericanos que le picaran las serpientes venenosas, sin el agua potable que tomaban los soldados yanquis; llenos de malaria, de parásitos, hambrientos, lucharon sin descanso contra el agresor de todos los tiempos. Por ellos siento un especial cariño. El trabajo que he realizado en esos lugares penetró muy adentro en mis sentimientos.

Q: Existen tres elementos básicos en su cine documental: la edición, la música y la gráfica. Sin embargo, Rebeca Chávez, que fuera asistente suya, lo califica como “el misterio de la intuición”. Cuando planifica un documental, ¿realmente surge como un fruto de la intuición?

A: Si la intuición tiene que ver con la magia y el misterio, es probable que sea verdad. Sin embargo, me parece que no es realmente lo más correcto decir que el trabajo mío es intuitivo solamente. Si yo no hubiera tenido la experiencia que tuve en mi vida, si no hubiera estado en los Estados Unidos, si no hubiera trabajado de lavaplatos en Nueva York, si no hubiera sido minero, si no hubiera realizado todo el trabajo anterior a cuando empecé a hacer cine, si no tuviera la experiencia de un joven rebelde ante la injusticia de su tiempo, si no hubiera trabajado en una hora de radio juvenil cuando tenía 14 y 15 años, porque tenía una vocación política, si no hubiera tenido todo este background, creo que la intuición no daría resultado.

Puede que sí, que haya algo desde un punto de vista «misterioso» de lo intuitivo, pero es que si lo intuitivo no va ligado a una realidad que uno ha vivido, la experiencia que ha tenido durante esa realidad, no se hubiera convertido en algo intuitivo.

Pongo en duda la concepción de intuición en relación con el trabajo, porque por muy intuitivo que uno sea, si tú no tienes una base cultural, una experiencia de la realidad que viviste, no creo que lo intuitivo saldría a flote. Hay quien cree que se nace sabio, pero nadie nace sabiéndolo todo; sino que a través del tiempo se educa, aprende, obtiene experiencias de la vida, recibe esa experiencia, la reelabora mentalmente, sentimentalmente; entonces sale lo intuitivo. Una vez explicado por mí qué estimo como intuitivo, si es lo que se comprende por el trabajo que he realizado en treinta años como cineasta, bueno, aceptemos entonces que es intuitivo.

Q: Una de las etapas importantes en su formación fue aquella en que trabajó vinculado a la música en una emisora radial. ¿Le ayudó a dominar el ritmo en cuanto a la música?

A: Sí, es un elemento en mi vida, una parte fundamental. por eso es que digo que lo intuitivo lo pongo en duda. Si no hubiera trabajado en el Departamento de archivos musicales de la emisora CMQ en la época en que lo hice, clasificando la música que se compraba para los programas radiales y de televisión, si no me hubiera entrenado en clasificar el sentimiento musical para ser usado después, no me habría dado cuenta de la capacidad de poder musicalizar algo con un sentimiento musical. Debido a que trabajé años allí, es posible que haya desarrollado una especie de temperamento musical, que aprendiera a utilizar la música para determinados momentos de una operación estética.

El hecho de haber estado en CMQ me facilitó ese entrenamiento, ese desarrollo del «oído musical». Siempre me ha gustado la música. He guardado los discos que me regalan; a mi esposa también le gusta la música y me ayuda mucho en eso de la clasificación para futuros momentos musicales que pueda utilizar.

Por eso insisto en que lo intuitivo es muy relativo porque sin ese entrenamiento, con mucha intuición, a lo mejor no hubiera logrado desarrollar ese «oído musical» para emplear la música en determinadas secuencias de un documental o de un noticiero.

Q: En el proceso de la creación, existen dos formas en que usted ha asumido el documental: unas veces como en Mi hermano Fidel, que fue un documental accidental, surgido como fruto de la entrevista realizada a Fidel Castro para el largometraje La guerra necesaria…

A: Un sub-producto.

Q: Sí, un subproducto magistral, pero, ¿existen documentales en los que usted ha elaborado el guión antes de filmarlos, o verdaderamente ha filmado y después reelaborado?

A: Jamás escribo guiones. Esta confesión a toda voz puede extrañar a muchos compañeros, no realizo los guiones convencionales con los que muchos colegas trabajan o los obligan a trabajar.

El guión de mis documentales está en mi cerebro y en mis sentimientos. Es como si yo fuera una computadora humana y tuviera un background de experiencias de la vida y entonces, de vez en cuando, apriete una tecla y produzca determinado hecho cinematográfico, o me remita a un pasado que me sirva de guión en el tiempo para poder realizar un trabajo determinado.

Por ejemplo, Now! es un documental que no nació por intuición ni por el arte misterioso de un creador. Nace porque previamente tenía la experiencia vivida en los Estados Unidos, lo que vi con mis propios ojos sobre la discriminación racial. En un momento determinado en que las circunstancias se tornaron propicias para hablar contra la discriminación, tuve ese hecho del pasado, almacenado en mi cerebro, y entonces lo utilicé para realizar Now!.

Escuché la canción Now! porque un líder negro, llamado Robert Williams, de visita en Cuba me regaló un disco. Visitaba su casa, era su amigo, y un buen día me puso un disco y dijo: “Mira a ver qué te parece esto”; y era la música de Hava Nagila. Le pregunté: “¿Tú me lo prestas?; ¿me lo regalas?”. Y me lo regaló. Entonces, de oírlo varias veces se me ocurrió realizar un documental exactamente con el tiempo que tiene esa canción.

Lógicamente, yo había pasado ya por una experiencia sobre lo que era la discriminación racial en los Estados Unidos y cuando escuché la música de Now!, empecé a retrotraer de mi archivo musical lo que habría de ser después el documental. No existió un guión sino todo un pasado que se impresionó en mi retina y en mis células cerebrales y cuando fui a poner en práctica el rechazo a esa situación política de discriminación racial, surgió la experiencia que tuve en un momento determinado, y pude realizar mi película.

El guión está en la propia canción, es decir, vas siguiendo la canción y escribes el guión, eso es en el caso de este documental.

En el caso de otros sobre Vietnam, ¿qué guión yo iba a hacer? No sabía lo que iba a pasar. Cuando llegamos, la guerra estaba caminando, y estaban a punto de empezar los bombardeos. Las noticias eran terribles sobre la agresión tremenda del imperio yanqui. Decidí ir a ese país para ser solidario con su pueblo, aunque no teníamos suficiente equipamiento; fuimos con una cámara de 16 milímetros de cuerda y con un popurrí de varios tipos de películas: inglesas, norteamericanas, italianas, que nos habían regalado las delegaciones que constantemente visitaban a Cuba al principio de la Revolución.

Con esas películas en blanco y negro, en 16 mm, de diferentes nacionalidades, con cámaras que cuando tú le das cuerda nada más que dura tres minutos la secuencia que estás filmando, entonces, tienes que volver a poner otro rollito, sin grabadoras, sin luces; yo llevaba una batería que me habían prestado los soviéticos cuando pasamos por Moscú; una batería que parecía un tanque, pesaba como diablo. Le llamaba palangana, y eso es lo que parecía: una palangana para iluminar. Ese fue el equipo que nosotros llevamos a Vietnam.

¿Qué guión iba a hacer? Al día siguiente de haber llegado, empezaron los bombardeos a Hanoi. Teníamos noticias de que en cualquier momento los norteamericanos iban a bombardear ciudades abiertas como la capital. De acuerdo con las leyes internacionales, no puede bombardearse una ciudad abierta; una ciudad no tiene propósito de invadir a alguien, ni guarda equipamientos militares. Sin embargo, así sucedió.

No sabía qué iba a suceder en el momento que estábamos allí. Ignoraba cómo iba a realizar el trabajo. El primer día que llegamos, empecé a buscar los lugares donde intuía que posiblemente podían empezar los bombardeos, como por ejemplo, el puente sobre el Río Rojo. Yo dije: «este puente seguro va a ser un blanco para ser bombardeado»; bueno, esa intuición de creer que iba a ser bombardeado; empecé a tomar notas de los lugares en que íbamos a filmar en el caso del inminente bombardeo a Hanoi. No existía ningún guión.

Sucedió el bombardeo, y de todo lo que filmamos indistintamente empezamos a ver, a buscar detalles adicionales para poder completar el hecho del bombardeo. Es en el cuarto de montaje, una vez que ya uno ve todos los rushes, los cuelga en el perchero, los analiza, que empieza a hacer un «guión», un posible guión de cómo va a montar la película.

Además, en tanto no me surge la idea de un título de un documental, no puedo empezar a montarlo, tengo que tener el título pensado ya para, a partir de él, comenzar a estructurar un documental cualquiera. El título, para mí, viene a ser como una célula donde se encuentran todos los hechos hereditarios que van a servir de elementos para conformar la idea después titulada guión; es decir, uno debe llevar cualquier hecho que quiera filmar como un diario: señalar lo que creas que es más importante en ese día. Ese diario lo conviertes después dentro del cuarto de montaje en una especie de cartilla o de guión. Hasta tanto no tienes todo el material revelado, los rushes, el título, inclusive ya estás pensando en la música. En resumen: yo edito y no hago como otros compañeros que hasta que no terminan de editar no le ponen la música, sino que voy simultáneamente preparando la música. En realidad, no existe un guión convencional.

Creo que el documental, igual que un noticiero, es «toma uno». El documental se parece mucho al trabajo del noticiero, es «toma uno» también. Esto te evita tener que usar un guión, porque lo vas preparando en la medida que vas filmando cosas, hechos que te van a servir después para unirlos en el montaje, poner una imagen tras otra, empiezas a utilizar el lenguaje típico del cine que es el montaje.

Q: El uso excepcional de la entrevista como recurso en su obra, que contrasta con el cine documental contemporáneo, no solamente cubano, donde existe un abuso de las entrevistas y escasa elaboración cinematográfica.

A: La mayor parte de mis documentales no tienen entrevistas ni tampoco narración; siempre trato de evitarlas. Cuando no me queda más remedio, las utilizo, como por ejemplo, en La guerra necesaria. Es otro estilo donde uso la narración, el locutor, pero deliberadamente, la mayor parte del trabajo que he realizado es sin narración oral. Y es la música, son las letras de las canciones las que utilizo como elemento narrativo del documental. El cine en estado puro, realmente.

Fall 2009, Volume VIII, Number 3

Manuel M. Hadad is Licenciado in Historia del Arte y Periodismo in the Universidad de Oriente (Santiago de Cuba). He works at the station Radio Victoria (Las Tunas). He is a film critic, member of UNEAC, the Unión de Periodistas de Cuba and the Asociación Cubana de la Prensa Cinematográfica.

Luciano Castillo is a Cuban film critic, researcher and historian. He has published many books including Con la locura de los sentidos; Ramón Peón, el hombre de los glóbulos negros, Carpentier en el reino de la imagen, El cine cubano a contraluz. He is head of the Mediateca “André Bazin” of the Escuela Internacional de Cine and TV de San Antonio de los Baños, member of the Consejo Nacional de la Unión de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba and Vice President of the Asociación Cubana de la Prensa Cinematográfica (subsidiary of the Filpresci).

Manuel M. Hadad es Licenciado en Historia del Arte y Periodismo en la Universidad de Oriente (Santiago de Cuba). Trabaja en la emisora Radio Victoria (Las Tunas). Es crítico de cine, miembro de la UNEAC, la Unión de Periodistas de Cuba y la Asociación Cubana de la Prensa Cinematográfica.

Luciano Castillo es un crítico, investigador e historiador de cine cubano. Ha publicado numerosos libros, entre ellos Con la locura de los sentidos; Ramón Peón, el hombre de los glóbulos negros, Carpentier en el reino de la imagen, El cine cubano a contraluz. Es titular de la Mediateca “André Bazin” de la Escuela Internacional de Cine y TV de San Antonio de los Baños, miembro del Consejo Nacional de la Unión de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba y Vicepresidente de la Asociación Cubana de la Prensa Cinematográfica. (filial de la Filpresci).

Related Articles

Coconut Milk in Coca Cola Bottles

Common knowledge has it that virtually any movie, once removed from its original cultural context of production and reception, might be either misunderstood and misperceived or re-interpreted and re-signified. Likewise, we may agree that national cinemas seek to define, challenge….

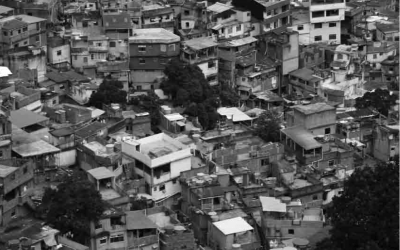

Neither the Sertão or the Favela

To frame the poetics of the ordinary in terms of subtlety and delicateness is to propose an antidote both for cynicism and for what I call Neo-Naturalism. Its appearance, at least in Brazilian cinema and literature, has been clearly identified, ranging from peripheral subjects…

Brazilian Cinema Now

Snow falling in the city of São Paulo, in southern Brazil? Taking a helicopter in São Paulo then arriving a few moments later in the deep wilderness of the Amazon jungle, half a continent further away to the north? Then meeting a white Asian tiger in the heart of the Amazon forest?…