Witnessing the Seeds of Liberation

Immigrant Detention and Pedagogical Encounter

Having first learned about liberation theology in college, I arrived at Harvard Divinity School in the mid 1990s with a desire to deepen my understanding of this historic movement. Through a class with theologian Harvey Cox, I was introduced to an insightful little primer by renowned Brazilian liberation theologians (and brothers), Leonardo and Clodovis Boff. The Boffs describe three levels through which liberation can be realized: the professional, the pastoral and the popular. As they explain, these levels are distinguished by their logic and language. While popular theology “will be expressed in everyday speech, with spontaneity and feeling,” professional theology “adopts a more scholarly language, with the structure and restraint proper to it” (1987). Residing in between the two, pastoral theology bridges these different languages through careful listening and earnest dialogue. The Boff brothers also use the metaphor of a tree to describe liberation theology’s three levels. They write:

“Those who see only professional theologians at work in [liberation theology] see only the branches of the tree. They fail to see the trunk, which is the thinking of priests and other pastoral ministers, let alone the roots beneath the soil that hold the whole tree—trunk and branches—in place. The roots are the practical living and thinking—though submerged and anonymous—going on in tens of thousands of base communities living out their faith and thinking it in a liberating key.”

I know from personal experience how easy it is, especially within the academy, to get swept up by the professional aspects of liberation theology and lose sight of the other two levels. As a graduate student, I found myself gravitating toward various “professional”-type, theoretical questions, such as how liberation theology was connected to a variety of other intellectual movements in Europe and how it resonated methodologically with important theological and philosophical traditions in the Americas, including Black theology, U.S. Latinx theology and U.S. pragmatism. But as worthwhile as these topics were, I was inclined, at least at first, to give scant attention to their connections to actual communities of faith. As I began to ponder a dissertation topic, I shared my conceptual interests with Davíd Carrasco, a trusted mentor (and the faculty consultant to this ReVista issue). He invited me to consider how my theoretical concerns manifest themselves in a concrete image, symbol or practice. “This will help others understand the importance of your question,” he advised. About that same time, I received another piece of sage advice from my dissertation director, theologian Francis Schüssler Fiorenza. Given that my dissertation was shaping up to be a study of the significance of John Dewey’s philosophy of religion for liberation theology, Schüssler Fiorenza encouraged me to immerse myself in the area for which Dewey is best known, his philosophy of education.

With these two suggestions in hand, I set out to explore how a set of Good Friday liturgies at the San Fernando Cathedral in San Antonio, Texas, educated ritual participants in ways that were liberating. With financial support from the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, I traveled to San Antonio during Holy Week to experience the liturgies firsthand as a participant observer. I also had numerous conversations with those who organized the liturgies as well as those who participated in them. As a result, my dissertation (and subsequent book) engaged liberation theology and philosophical pragmatism not only at a theoretical, or “professional,” level, but also at the level of pastoral education and popular religious experience.

I am thankful to have had mentors who helped me appreciate the ways in which liberation theology is organically connected at all three levels. I have also learned much from Latin American and Latina feminists—such as María Pilar Aquino, Ada María Isasi-Díaz, and Ivone Gebara—who foreground the theological significance of everyday life (lo cotidiano). The work of Filipino theologian Daniel Pilario has been another inspiration. In his exceptional study of French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of practice and its significance for theological method, Pilario points out that there is indeed a time and a place for scholars to parse out the theoretical significance of faith praxis. However, as he shows, this conversation is aided significantly when scholars dare to immerse themselves in what he calls the “rough grounds” of praxis (2005). In Pilario’s case, this leads him to ask: What does it mean to do theology in the context of those who work and live in Payatas, the largest garbage dump in Manila, Philippines? As a scholar, Pilario diligently teases out the theoretical complexities of the question. But as a pastoral minister who directly serves those who live and work in the garbage dump, Pilario is also deftly attuned to how the rough grounds of Payatas may add significant depth and nuance to the theoretical question at hand. Like the work of Latin American and Latina feminists, his work invites us to thread the needle between the professional, pastoral and popular levels of liberation theology.

Over the past twenty years, I have been thinking and writing about these connections mostly in my professional capacity as a scholar of religion. However, more recently— and on a more personal level—I have been fortunate to witness the seeds of liberation taking root through my volunteer work with detained immigrants. Over the past five years, before Covid-19 changed everything, I drove once a month to a detention facility, about an hour from my home, to sit with detained immigrants and listen to their stories. I did so as a volunteer with the Chicago-based Interfaith Community for Detained Immigrants (ICDI), an organization that provides support for immigrants caught in the immigration detention process.

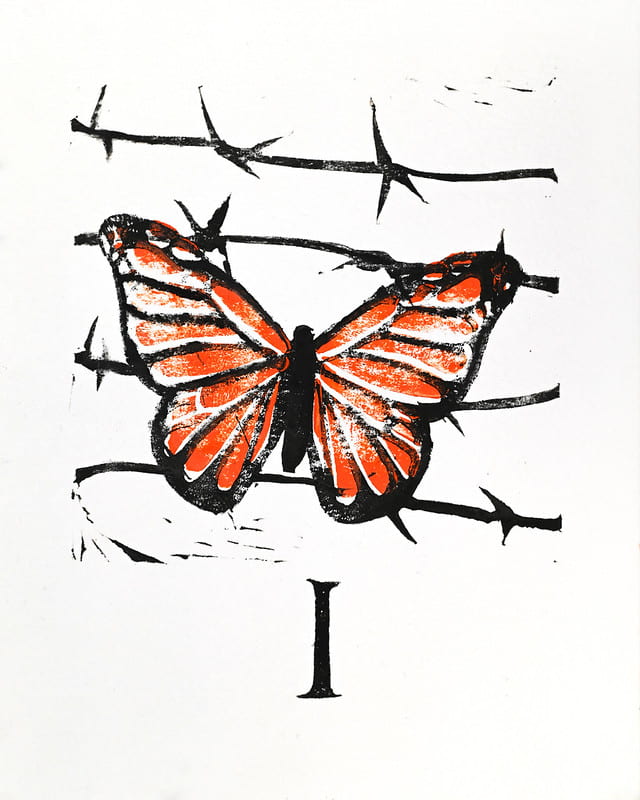

I. Jesus is Condemned to Death. Just as thorns are used to deter Jesus from continuing his mission, so too is barbed wire used to deter the migrant from crossing the border. Once caught, Jesus and the Monarca Migrante are scapegoated and denounced. Artwork and description by Jaqueline Romo. Photo courtesy of Juan García and Ryan Pagelow.

As the name of the organization indicates, ICDI is an intentionally interfaith affair. Founded by two determined Catholic sisters (both Sisters of Mercy), the organization welcomes volunteers from all (and no) religious traditions to participate in the work of immigrant accompaniment and solidarity. The Jail Visitation program I participated in was one several outreach efforts sponsored by the organization. At the time, ICDI supported five other robust ministries (http://icdichicago.org/).

Those of us who volunteered in the Jail Visitation program would spend a little over two hours meeting with detained individuals, the vast majority of whom were men. We usually did so in three successive sessions consisting of three to five individuals each. Many of the men we met were young (18- to 22-years-old) and had been recently detained. All they had seen of the United States were a series of detention facilities, as they were often shuffled from one to the next. Some of the men were older (anywhere from 25- to 65-years of age) and had lived in the United States for years, if not decades. Many had spouses and children who are U.S. citizens. More than anything, these long-time residents simply wanted to be reunited with their families. Most all detainees were born in Latin America, but it was not uncommon to see others from Africa, Asia and Europe. Accordingly, although the majority of our conversations were in Spanish, some volunteers also led discussions in English or French. In addition, one or two members of our volunteer group would spend part of the time meeting with a smaller group of detained women (mostly from Latin America) in another part of the jail.

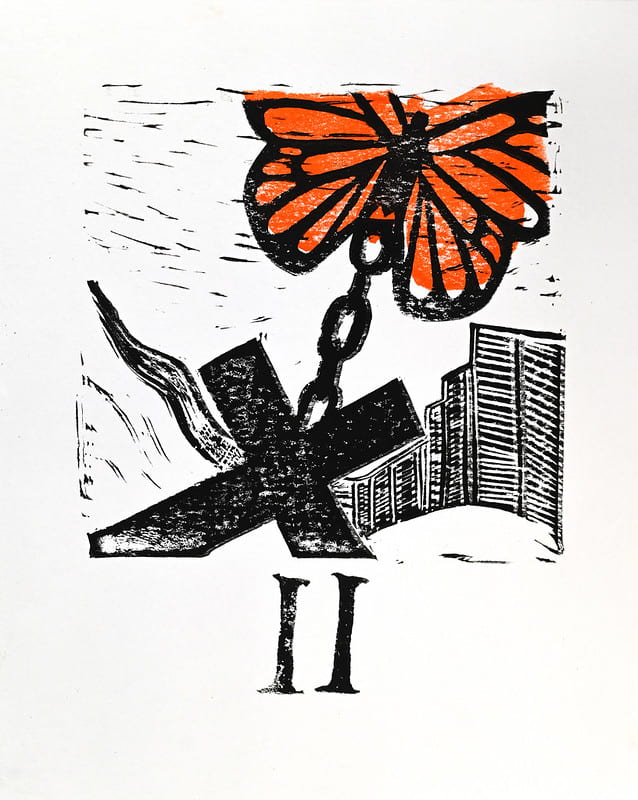

II. Jesus Carries His Cross. Like Jesus, the Monarca Migrante is chained to a heavy cross. It must carry the burdens of oppression, marginalization, violence, poverty, and hunger, all in order just to survive. Artwork and description by Jaqueline Romo. Photo courtesy of Juan García and Ryan Pagelow.

Our role as ICDI volunteers was relatively straightforward: we were there to listen to these individuals and let them know that they were not forgotten. Sometimes, our conversations were filled with light-hearted small talk. On any given day, we might discuss their previous line of work (many detainees previously worked as cooks or construction workers), or what they did for recreation in the detention facility (with limited options, many passed their time watching television), or what kinds of food they most look forward to eating again once they were released (the jail’s largely soy-based diet was disliked by every inmate with whom I spoke). Other times, our conversations would turn to weightier topics. Recently arrived detainees often expressed great worry about returning to their place of birth given the threat of gang violence in their home countries. For example, “Edwin” from Honduras (I’m using pseudonyms here to protect privacy) explained how both his father and brother had been killed by a cartel in his small hometown and that if he returned, he would surely be next. Many long-time U.S. residents expressed concern over no longer being able to support their families, and many appeared visibly shaken by the prospect of not being able to see their family again in the United States. Such was the case with Bertín, who was born in Mexico but who had been living in the Midwest for more than 25 years with his wife and five children, ages 14, 12, 10, 6 and 3, all U.S. citizens.

Without a doubt, inmates found the experience of being in detention fiercely disorienting. Speaking of his experience with detention officials and other officers from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), Jacinto from El Salvador noted that “they treat us as if we were animals.” This sentiment was expressed frequently among inmates. With minimal exercise options, inmates were also often bored and, in some cases, depressed. As Luis from Mexico told me, “Sometimes after breakfast, I return to bed and try and go back to sleep.” Making matters even worse, many inmates had no clear sense of how long they would be in detention, especially if their case was being appealed. While most inmates were typically detained for three to six months, it was not uncommon to encounter immigrants who had been detained for more than a year. Unlike traditional prisoners, immigrant detainees are not guaranteed a public defender under U.S. law. As such, many inmates could not afford a lawyer and were left to navigate the labyrinthian court system almost entirely on their own.

As unpleasant and disorienting as these experiences were, many inmates nevertheless approached their time in detention as an opportunity to engage in significant forms of re-orientation. Many reflected deeply on their life, their priorities and their relationship with God. While some looked to the past, others focused on their present circumstances and the underlying social forces that brought them to this point in their life. Many said they had become disillusioned with the “American Dream” and tired of the myriad ways they were looked down upon because of their language, economic status and/or the color of their skin. “If I do end up back in my home country,” Israel from Mexico told me, “at least I know I will be treated like a human being.” Like Israel, many inmates were going through a process of what Brazilian educator Paulo Freire calls “conscientization”: they were coming to terms with the root causes of their present circumstance and, in the process, affirming their own humanity and agency (1970).

III. Jesus falls for the First Time. The pain of Jesus and the migrant is real. The migrant quickly confronts unknown terrain, high temperatures, injuries, and extreme thirst. The Monarca Migrante loses a part of itself in its debilitating first fall. Artwork and description by Jaqueline Romo. Photo courtesy of Juan García and Ryan Pagelow.

I, along with my fellow volunteers, found it striking that in spite of the tremendous hardships that the inmates faced in detention, they often expressed a profound gratitude for the very little that they did have—be it as simple as the present moment, their health, the safety of their family members, another day of life. Inmates often connected their gratitude to their faith in God, as when they would frequently add to their comments phrases such as “si Dios quiere,” “con el favor de Dios” or “gracias a Dios.” It is worth noting here that many of the individuals with whom I spoke had only loose ties to religion in its formal sense. While most considered themselves Catholic or Christian, a majority acknowledged that they attended church infrequently, even in the best of times. That said, it is fair to say that these men were deeply spiritual given the reverence and gratitude they expressed for the small things in life. Many pointed out that their time in detention had afforded them opportunities to pray more, read the Bible and grow deeper in their faith. As Juan from Guatemala shared, “Before [detention], I didn’t read the Bible. I didn’t have time for God. Now, my situation has made me think. I have come to analyze things [“me ha puesto pensar; llegué a analizar”]. And I have asked for forgiveness for the way I used bad words and didn’t respect people.” Toward the end of his comments, he added: “God is good. God does not fail us.”

The more time I spent with detainees, the more I began to appreciate the pedagogical and therapeutic dimensions of immigrant accompaniment. John Dewey describes education, at its most fundamental level, as the reconstruction of experience that both adds to the meaning of experience and helps to direct the course of subsequent experience (1916). As ICDI volunteers, we fulfilled a basic educational role insofar that we helped to structure and facilitate conversations with and among detainees. That said, a much more deep-seated form of education took place when detainees would accompany, encounter and, in Dewey’s sense, “educate” each other.

One clear example of this occurred two winters ago when we had to improvise a session with inmates. Because of a heavy snow storm, only two other volunteers and I made it to the jail. We were confronted with a daunting task. Close to thirty inmates were expected in our first session. We knew instantly that we needed to change our format. Rather than having the usual luxury of each of us meeting with three to five inmates, we had no other choice but to break the men up into their own small groups of four to five and have them discuss three questions among themselves: 1) How are you doing in this moment? 2) What are you thankful for today? and 3) What do you most look forward to when you are no longer in detention? As I wandered around the room, observed body language, and listened in on conversations, I was struck by their level of engagement. Letting everyone speak his turn, they listened closely to each other and supported one another. We then invited individuals from the small groups to share relevant insights with the large group, and, again, the responses were honest and real. The men were clearly ministering to each other, and a sense of goodwill permeated the room.

Bringing the session to a close, a fellow volunteer (a beloved Dominican sister who visited the men weekly) thanked them for sharing and underscored what a privilege it was for us, as volunteers, to hear their stories and learn from them. Normally, we would then pass around a handout featuring various interfaith prayers and recite one together. This time, however, we asked if any of them would be interested in leading the group in prayer. A young man in his mid-twenties rose to his feet and volunteered. (As it turns out, there is commonly at least one detainee—usually a self-identified “Cristiano,” as opposed to “Católico”—who, independent of our ICDI-gatherings, serves as an informal Bible-study leader for detainees who are interested. This man was clearly someone who served in that role.) He invited the men to join hands, and with all the eloquence and grace of a seasoned preacher, he delivered one of the most heartfelt and moving prayers that I have ever heard. He spoke of gratitude, perseverance and hope, and he did so in a way that was welcoming to all. With their eyes closed, the men listened attentively, and at least one became visibly emotional. In that moment, his words and vision gave added meaning and depth to the men’s shared experience, and it provided a framework of hope that the men could draw on when faced with challenges that were most certainly yet to come. This prayer leader was not only a compañero who felt these men’s pains firsthand; he was also a guide and a teacher who helped to bring life to those who so acutely needed it.

Are such experiences emblematic of liberation theology? Can they properly be included in a discussion of this watershed movement? If one were to ask the question solely from the standpoint of liberation theology’s scholarly texts, one might be inclined to say “no,” given that the inmates did not engage in any kind of formal theological study. Such an interpretation, however, would miss the point that liberation theology can—and does—manifest itself on multiple levels. As the Boffs remind us, liberation theology may be “expressed in everyday speech, with spontaneity and feeling.” Although the technical language of liberation theology may not have been explicitly invoked in our exchanges with detained immigrants, many of its central themes—such as conscientization, a preferential option for the poor, salvation in the here-and-now and engaged praxis— arose implicitly. But even this fact may be somewhat beside the point. Perhaps the greater insight here is that, regardless if we call it liberation theology or not, volunteers and detainees alike actively cultivated experiences of liberation through a pedagogy of accompaniment and encounter.

Saint Óscar Romero of El Salvador, a revered pastor and teacher, understood well what it meant to cultivate experiences of liberation through accompaniment and encounter. A prayer that is often attributed to him sums up his perspective well. (The prayer, entitled “Prophets of a Future Not Our Own,” was penned in 1979 by Bishop Ken Untener of Saginaw, Michigan, and was quoted by Pope Francis in 2015.) A section of the prayer goes like this:

We plant the seeds that one day will grow.

We water seeds already planted, knowing that they hold future promise.

We lay foundations that will need further development.

We provide yeast that produces far beyond our capabilities.

We cannot do everything, and there is a sense of liberation in realizing that.

This enables us to do something, and to do it very well.

It may be incomplete, but it is a beginning, a step along the way, an

opportunity for the Lord’s grace to enter and do the rest.

In the above passage, to whom does the “we” refer? Romero and the Boff brothers would most assuredly say that the work of planting seeds extends to all, from scholar-practitioners at the professional level, to ministerial leaders at the pastoral level, to everyday people at the popular level. And they would no doubt add that each of these levels should be informed by and centered around the lived experience of the most marginalized members of our society. I consider myself lucky to have had mentors in graduate school who encouraged me to approach my theoretical interests in light of the concrete faith expressions of a people. Years later, my volunteer experience with ICDI has once again illuminated the latent riches that abide in the “rough grounds” of faith. In these neglected spaces, I have encountered fellow human beings who, at first glance, may seem to have very little but who, in fact, have so much to offer.

One need not travel to the streets of San Antonio, a garbage dump in the Philippines or a detention center in the Midwest to experience these rough grounds. They exist everywhere and in every community. Part of the enormous challenge, however, is that we as a society often find it so much easier to look the other way. We would all do well, instead, to listen and learn.

Winter 2021, Volume XX, Number 2

Christopher Tirres is the Inaugural Endowed Professor of Diplomacy and Interreligious Engagement at DePaul University. He is the author of The Ethics and Aesthetics of Faith: A Dialogue between Liberationist and Pragmatic Thought (Oxford, 2014) and the forthcoming Liberating Spiritualities in the Américas (Fordham). As a graduate student, he helped to found DRCLAS’s Latin American and Latino Forum and served as its first Art Coordinator.

Related Articles

Indigenous Peoples, Active Agents

Recently, the Amazon and its indigenous residents have become hot issues, metaphorically as well as climatically. News stories around the world have documented raging and relatively…

Beyond the Sociology Books

If you are not from Colombia and hoping to understand the South American nation of 50 million souls, you might tend to focus on “Colombia the terrible”—narcotics and decades of socio-political violence…

Exodus Testimonios

The audience at Iglesia Monte de Sion was ecstatic as believers lined up to share their testimonials. “God delivered us from Egypt and brought us to the Promised Land,” said José as he shared his testimonio with the small Latinx Pentecostal church in central California…