Women Writers in the 21st Century

The Porcupine’s Prick

Just as I was returning to Caribbean studies, Mayra Santos-Febres suggested that I write the introduction for Las espinas del erizo: antología de escritoras boricuas del siglo XXI (The Porcupine’s Quills: Anthology of Puerto Rican Women Writers). Working on my doctorate at Harvard, I’d taken a detour through the Southern Cone with its imposing paternal figures. As a woman from Puerto Rico, I couldn’t think of a more suitable project than Mayra’s invitation (and challenge).

It was a welcomed opportunity to immerse myself in the worlds of imagination created by the contemporary pens of 21st century women writers who were joining this “commonwealth” called Puerto Rican literature. I found this invitation a tempting incentive to contribute a preliminary study and thus to participate as a critical observer. I decided to accept.

In what fashion are these Puerto Rican escritoras, women writers, laying siege to the traditional literary canon? It was easy for me to recognize that the Island’s system of narrative, even when embedded in the discourse of colonialism and docility, has shared many characteristics with the discursive style of the sovereign patriarchs. According to Puerto Rican critic Juan Gelpí in Literatura y paternalismo en Puerto Rico, Puerto Rican literature was traditionally governed by the concept of literary generations, which in turn revolved around a central father figure. The production of the new women writers was articulated as a corpus—a body of work—that challenged or provided an irritant to what could be considered the first generation of Puerto Rican women writers. As the principal interlocutor in this anthology, this generation emerged in the 1970s as a result of a distancing that undermined the masculine canon, the disfiguration of the father figure and the emergence of the idea of nation as a “house in ruins,” to continue with Gelpí’s metaphor. Santos-Febres argues that this generation of women writers solidified the feminine literary canon in Puerto Rico and internationalized Puerto Rican literature as a whole.

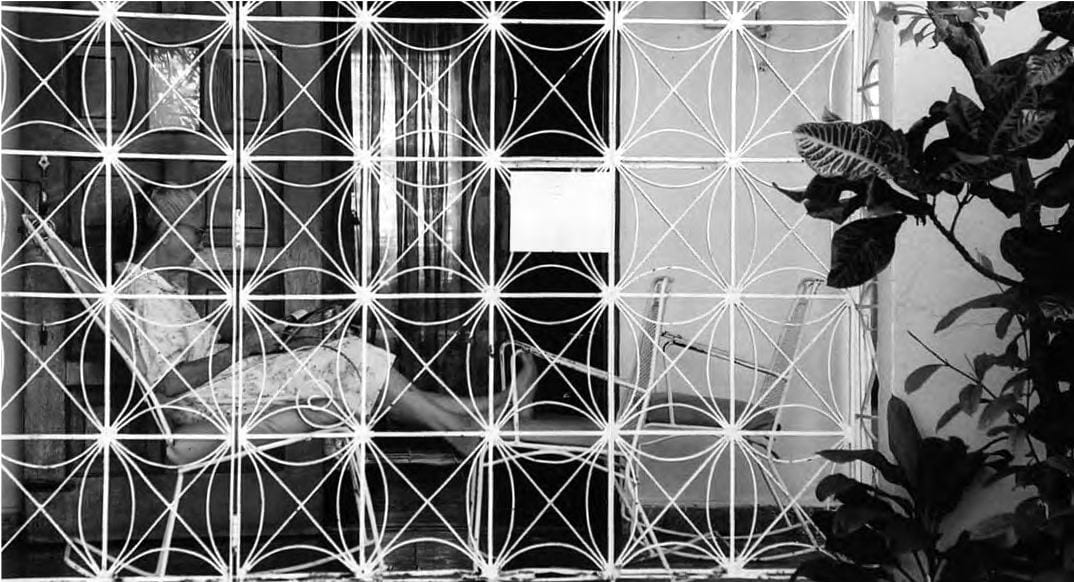

The women writers—innovative and irreverent when they burst upon the literary scene in the waning years of the 20th century—emerged terrified but exuberant through the windows of the “house in ruins” of Puerto Rican literature. As Ramón Luis Acevedo points out in Del silencio al estallido: Narrativa feminina puertoriqueña, the 60s—and the women writers who began to publish then—paved the way for the noisy “boom” of women writers in the 70s. And, ironically, at times, these women writers are invited to cohabit in this anthology in a new house of writing localized in the globalized world of the 21st century. It is a new world that has preserved an acoustic memory of 1960s and 1970s icons, such as these female predecessors or other pop figures of the time, like Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” incursion into Mara Pastor’s “Un completo desconocido.

As an editor, Santos-Febres brings together these texts to produce an understanding that “challenges the formal paradigms of the generation of ’70 and its most important representatives: Ana Lydia Vega, Rosario Ferré, Olga Nolla and Mayra Montero.” The anthology is dedicated to these teachers, these “female masters,” the narrators of ’70, “for having forged a path that I,”says Santos-Febres, “(and many other women) have followed.” The anthology is organized with these literary matriarchs, but also against them. They are the primary interlocutors even if some of the writers in the anthology directly address the masculine literary canon of Puerto Rican and Latin American letters, such as Neeltje Van Marising Méndez’s Yo maté a Abelardo Díaz Alfaro, Sofía Cardona’s La amante de Borges, or Alexa Pagán’s El Cisne, a queered allusion to Rubén Darío’s powerful literary symbol. What are the “formal paradigms” of the generation of ’70 that the new women writers are challenging? Some examples of these paradigms are the use of popular speech as a literary language; the exaltation of the working classes; and a focus on Latin American and Caribbean identity. In the case of many of these older women writers, the paradigm also involves feminine and feminist identity. The new women writers introduced by Santos-Febres distance themselves from these narrative emphases; if these themes do figure in the anthology, they do not dominate it.

The anthology’s texts do not follow a single coherent narrative paradigm. It is important to remember that these writers do not constitute a new generation. Santos-Febres explains in her preface, “I do not follow strictly generational criteria; some of these divas were born before a lot of the others.” She clarifies, “I am focusing on a more solid foundation.” The silence about new Puerto Rican literary production forms part of this “more solid foundation.” There has not been a literary anthology of new Puerto Rican women writers since 1986. “It is as though the literary world had ended on the Island after ’70,” says Santos-Febres. “In part, this is because of the fragmentation of literary collectives, the growing tendency toward Internet publications and, perhaps as a result, exclusively local publishing.” The editor, therefore, extends an invitation to read the anthology in the context of the profound silence surrounding contemporary literature in today’s Puerto Rico.

Although her public persona has projected her on the Island as the contemporary national literary matriarch, Santos-Febres and her edited volume do not seek to inscribe her in that role. Las espinas del erizo: antología de escritoras boricuas del siglo XXI places the women writers in a century that searches deeper but does not venerate the model of literary generations and their imposing patriarchs and now, more recently, their equally imposing matriarchs.

This anthology is organized with a pace that is most closely associated with that of the literary workshop, a very popular phenomenon in the world of Puerto Rican letters. The momentum of a workshop is not genealogical nor vertical; rather, it is closer to the rhizomatic model of French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in which a plant assumes very diverse forms, from ramified surface extension in all directions to concretion into bulbs and tubers. This model has had faraway echoes throughout the Caribbean in the works of Martinique author Edouard Glissant, Cuban writer Antonio Benítez Rojo and Santos-Febres herself.

“Every writer needs her or his workshop,” Santos-Febres wrote in 2005 in the prologue to Cuentos de oficio: Antología de cuentistas emergentes en Puerto Rico, referring in a meta-literary fashion to the process of forming craftspersons in the world of letters. This 2005 anthology, product of literary workshops Santos-Febres has led throughout the Island for decades, follows the model of volumes of short stories published as a result of workshops, such as that of Luís López Nieves’Te traigo un cuento and Mayra Montero’s Vientitrés y una tortuga. In Puerto Rico, the literary workshop has had an important role in the development of narrative since the 1950s when Enrique Laguerre established the first literary workshop at the University of Puerto Rico. Many writers have offered workshops since then. It is significant that it is Santos-Febres—a hallowed woman writer in the Puerto Rican literary world and indeed throughout much of the Spanish-speaking Caribbean—who proposes the re-ordering of Puerto Rican literary history.

While this anthology is inscribed in a literary framework, it reformulates the conceptions of prior anthologies. Las espinas del erizo does not bring together women writers who obediently stick to the model of the inviting editor. On the contrary, in this anthology’s pages, we find a diversity of voices. These voices do not attempt to explain the identity of “woman,” even when they would agree with gender theorist Judith Butler when she asks, “What does gender want of me?”—conceiving the identifying category “gender” as an antecedent to one’s very subjectivity (Judith Butler, “What Does Gender Want of Me? New Psychoanalytic Perspectives,” magistral speech at the Program of Studies of Women, Gender and Sexuality, Harvard University. Dec. 4, 2007). Identity in this anthology is not based on nationality/ethnicity/race or even Puerto Rican or Caribbean identity. All these identities are taken as a given or conveniently overlooked.

What stands out in each story are women “bregando.” a very Puerto Rican word meaning “fending,” “dealing with,” “coping” or “getting by” or a mix of all of the above. This ubiquitous term, studied by writer Arcadio Díaz-Quiñones in his El arte de bregar: Ensayos (San Juan: Ediciones Callejón, 2000), has multiple meanings. According to Díaz Quiñones, “the verb bregar floats, wise and entertaining, in the multiple scenarios of Puerto Rican life…women and men employ this verb endlessly, with freedom and intelligence. Puerto Ricans are always fending for themselves, vulnerable, alert…bregar is, one could say, another way of knowing, a diffuse method without a compass to navigate everyday life, where everything is extremely precarious, changing or violent…” The women of this new literature “bregan” as protagonists; their kind of dealing with the world is not just a passive backdrop. They are women who go beyond their private worlds, who inhabit the public sphere in Puerto Rico, the Caribbean and other undefined spheres.

The category “citizen” is fundamental for these new literary subjects. Says Santos-Febres, “The fact is that women appear as agents in these worlds. She passes through them, changes them, and is changed by them; she explores them, now not from the private sphere (as mother, wife, lover, etc., but as a citizen/marginal person/professional woman/traveler, etc. From another gaze.”

This other perspective or, in more literary terms, “gaze,” also affects the way women see the world of the private sphere, as occurs in Mara Negón’s Carta al padre, a text that establishes similarities and contrasts with the generation of ’70 and, also with other some contemporary writers, namely Rita Indiana Hernández, a young Dominican writer who’s a frequent participant of the Puerto Rican cultural scene. Hernández’s novel Papí (San Juan: Ediciones Vértigo, 2005), is a counter point to Negrón’s Carta al padre. The masculine figure is inscribed as a pretext in Carta al padre, while Negrón’s narrative thread explores the father-daughter relationship, a long way from the tense and traumatized depiction of the masculine figure in Hernández’s novel or in the previous ‘70s narrative. This new writing avoids portraying the masculine figure as an Ambrosio, character in Rosario Ferré’s short story,”Cuando las mujeres quieren a los hombres,” in which the shadow of a fearsome man gives rise to unanticipated female solidarity. Formed in Paris under the tutelage of Hélène Cixous, Negrón has become an important disseminator of French-style feminism on the Island. This father figure is her own Caribbean re-elaboration of and detour from the theoretical French construct. The memory of the father, absent and yearned after, is the basis that permits the daughter to explore her own pleasure (jouissance).

The absence of the father figure, a recurrent theme in contemporary Caribbean societies, is responded to by the pleasure of the daughter, a narrative situation that differs from that of Papí. Hernández’ text reflects the fury of a deprived youth on the streets of Santo Domingo, brought up in the swamps of Balaguer’s paternalism. Eventually, after becoming successful, this protagonist’s father leads the life of a 40-something rich guy, commuting between the barrio and Miami. In the process, he turns his back on his daughter. Papí is her furious complaint about her father’s abandonment. In this sense, Hernández is in tune with 20th century Puerto Rican women writers, despite the fact that the story clearly takes place in a post-modern 21st century Caribbean context. Far from the fury, the complaints and outbursts of this type of literature, Carta al padrepresents a taking of pleasure in an interior world in each sentence and on each page. The father is only a pretext.

Negrón’s text is only one example of the conversations taking place in this wide-ranging anthology. The volume encompasses social critique, fantasy, the erotic and intimate perspective, and historical fiction. The tones are as diverse as the writers. So are the plots and narrative techniques. However, none of these stories engages in “pamphleteering.” The stories do not seek to invoke “poetic justice.” They simply explore the condition of being a woman in this world, of being a woman in a globalized world that is still deeply patriarchal. “The reason I want to present the women writers is that they (enter into) the culture of globalization from the vantage point of Puerto Rico,” writes Santos-Febrés in her introduction.

According to Santos-Febrés, the texts of these twelve writers are the spines of a sea urchin which “with different rhythms, embed themselves in the unwary skin of Puerto Rican literature.” With her title, Santos-Febrés inscribes and challenges the cultural tradition of the femme fatale and her toothed vagina, giving it a Caribbean twist and vindicating a shrill, irritating and indeed unfathomable image. The sea urchins, like the women writers in this anthology, are creatures that live comfortably and complacently in the environment, but creatures that also are balls of barbed wire. This house of writing opens the way to an immense and often hostile environment in which these sea urchins live, these creature who enter into contact by making themselves felt.

Mayra Santos-Febres y Las Escritoras Boricuas del Siglo XXI

The Porcupine’s Prick

Por Carmen Oquendo-Villar

Caminaban Franca y Fina una tarde calurosa en dirección al fuerte de San Felipe del Morro, buscando un poco de alivio para sus respectivas pelambres en la fresca brisa que se levantaba del Atlántico, cuando se entabló entre ellas una conversación memorable. Perras sabias y trotamundos retomaban siempre, en sus paseos vespertinos por las calles del viejo San Juan, algún tema literario que les apasionaba y que solían examinar extensamente mientras desahogaban, frente a algún paisaje digno de Francisco Oller y entre aguas mayores y menores, las exigencias naturales del cuerpo y del alma.

— Rosario Ferré

El coloquio de las perras

Mayra Santos-Febres me propuso escribir el prólogo para una antología, Las espinas del erizo: antología de escritoras boricuas del siglo XXI, justo cuando retomaba mis estudios sobre el Caribe; después de un desvío al Cono Sur—y sus imponentes figuras paternas—para refrescar los consabidos discursos caribeños. No había proyecto más adecuado que esta invitación (y reto) que me proponía Mayra: zambullirme en el imaginario vislumbrado por las escritoras de nueva tinta que se suman, desde el siglo XXI, a ese “bien común” llamado literatura puertorriqueña. Encontré muy tentadora esta invitación de aportar con un estudio preliminar y así participar observando críticamente esta intervención en el canon isleño. Acepté.

¿Desde dónde asediaban las nuevas escritoras el canon? Fue fácil reconocer que el sistema narrativo isleño, aún cuando estuviera enfrascado en el discurso del colonialismo y la docilidad, ha compartido muchas características de la discursividad de los patriarcados soberanos. Según Juan Gelpí, en Literatura y paternalismo en Puerto Rico, este canon fue tradicionalmente regido por el concepto de generación literaria, la cual giraba en torno a la gran figura central del padre. El trabajo de las nuevas escritoras se articula como un corpus que reta o irrita lo que podría considerarse la primera “generación” de escritoras mujeres. Interlocutora principal de esta antología, esa generación surgió en los años setenta a partir del distanciamiento que socavó el canon masculino, la desfiguración de la figura patriarcal, y el surgimiento de la idea de la nación como una “casa en ruinas,” para continuar con la metáfora de Gelpí. Santos-Febres argumenta que fue esta generación de escritoras la que solidificó el canon literario femenino en el país e internacionalizó la literatura puertorriqueña en general.

Las escritoras—innovadoras e irreverentes cuando irrumpieron en el panorama literario de las postrimerías del siglo veinte—salían entonces despavoridas pero exhuberantes por las ventanas de la “casa en ruinas” de la literatura nacional. E, irónicamente, a veces tan celosas de la soberana de la casa nacional como los patriarcas. Ahora, en el 2008, ellas mismas son invitadas a co-habitar en esta antología una nueva casa de la escritura localizada en un globalizado siglo XXI. El trabajo editorial de Santos Febres agrupa estos textos por entender que “reta[n] los paradigmas formales de la generación del 70 y de sus más importantes representantes: Ana Lydia Vega, Rosario Ferré, Magali García Ramis, Olga Nolla y Mayra Montero” (2). A estas “Maestras”, las narradoras del 70, va dedicada la antología, por “haber abierto el camino que ahora yo (y otras muchas) recorremos” (6).

Con esas madres y contra ellas se organiza esta antología. ¿Cuáles son los “paradigmas formales” de la generación del setenta que retan las nuevas escritoras de Las espinas del erizo? Entre ellos se encuentran: el habla popular como lengua literaria, la exaltación de las clases populares, la identidad caribeña y latinoamericana. En el caso de muchas, la presencia femenina y feminista. Las nuevas escritoras que nos presenta Santos Febres se alejan de esas modalidades narrativas, y si las incorporan, no dominan la narrativa.

Los textos de esta antología no siguen un paradigma narrativo coherente. Es importante recordar que no se trata de una nueva generación. “No sigo”—dice Santos Febres en el antologario—“criterios estrictamente generacionales—algunas de esta divas nacieron antes, mucho antes que otras.” Clarifica: “Me dirige fundamento mayor.” (2) El silencio con respecto a la nueva producción literaria boricua forma parte de este “fundamento mayor.” En términos de la producción literaria de escritoras, no había habido una antología desde 1986 de escritoras de nuevas tintas. En las décadas de los ochenta y noventa aparecieron dos antologías pero en su mayor ía de las escritoras ya consagradas, como es el caso de las siguientes tres. Ramón Luis Acevedo, Del silencio al estallido: Narrativa femenina puertorriqueña (Río Piedras: Editorial Cultural, 1991), María M. Solá, Aquí cuentan las mujeres. Muestra y estudio de cinco narradoras puertorriqueñas (Río Piedras: Editorial Huracán, 1990), y Diana Vélez, Reclaiming Medusa: Short Stories by Contemporary Puerto Rican Women (San Francisco: Spinsters/Aunt Lute Book Company, 1988). “Es como si después del 70 se hubiera acabado el mundo literario en la Isla”—dice Santos Febres—“Esto se debe en parte a la fragmentación de colectivos literarios, a la publicación mayormente en internet y no sé si consecuentemente, a una publicación mermada en editoriales locales” (3-4). La editora extiende, pues, una invitación a la lectura en el contexto de ese profundo silencio con respecto a la literatura actual en Puerto Rico.

Aunque su persona pública se haya configurado en el espacio público isleño como matrona nacional, Santos Febres y su presente trabajo editorial no buscan inscribir su figura como la matrona literaria de la contemporaneidad. Las espinas del erizo: antología de escritoras boricuas del siglo XXI ubica a las escritoras en el siglo que se adentra sin acatar el modelo de generación literaria y sus imponentes padres y, ahora más recientemente, madres igualmente imponentes. Lo que organiza esta antología es un impulso más cercano a la tradición del taller literario, fenómeno con mucha acogida en las letras puertorriqueñas. El impulso del taller no es genealógico ni vertical, sino cercano al modelo rizomático de Deleuze y Guattari, el cual ha tenido ecos lejanos en el Caribe, como en la obra del martiniqueño Edouard Glissant, el cubano Antonio Benítez Rojo y de la propia Santos-Febres.

“Todo escritor requiere su taller” escribía en 2005 la misma Santos Febres en el prólogo a Cuentos de oficio: Antología de cuentistas emergentes en Puerto Rico, aludiendo metaliterariamente al proceso de formar oficiantes en el mundo de las letras. Esa antología de 2005, producto de los talleres literarios que Santos-Febres lleva impartiendo por décadas en la isla, se adhería al modelo de publicación de tomos de cuentos de talleristas, como lo habían hecho antes Luis López Nieves en suTe traigo un cuento y Mayra Montero en Veintitrés y una tortuga. En Puerto Rico el taller literario ha tenido un importante desarrollo de su literatura a partir de mediados del siglo veinte. Enrique Laguerre fundó en los años cincuenta el primer taller de narrativa en la Universidad de Puerto Rico. Entre los escritores que han ofrecido talleres, sobre todo de cuento, se encuentran Luis López Nieves, Emilio Díaz Valcárcel, Mayra Montero, Edgardo Rodríguez Juliá. Escritora formada ella misma bajo la mentoría de los escritores Ché Melendes y Angelamaría Dávila, Santos-Febres ahora nos presenta en Las espinas del erizo: Antología de escritoras boricuas del siglo XXI una selección del trabajo de las nuevas escritoras que, aunque no fueran necesariamente formadas en su taller, han sido definitivamente acogidas bajo su ala y mentoría. Y es significativo que sea Mayra—escritora consagrada en las letras nacionales e incluso en todo el Caribe hispano—quien proponga este reordenamiento de la historia literaria boricua.

Si bien se inscribe en este marco literario, la presente antología reformula concepciones antológicas previas. Las espinas del erizo no reúne escritoras que acatan obedientemente el modelo de quien las convoca. Por el contrario, en las páginas de la antología encontramos una diversidad de acercamientos y maniobras retóricas. Estas voces no intentan explicar la identidad “mujer’ aun cuando pudieran coincidir con Judith Butler cuando ésta se pregunta—¿qué quiere el género de mí?—pensando en la categoría identificatoria “género” que antecede la subjetividad misma. (Judith Butler, What Does Gender Want of Me? New Psychoanalytic Perspectives, Conferencia Magistral en el Programa de Studies of Women, Gender and Sexuality, Harvard University, 4 de diciembre, 2007). Tampoco definen una “identidad” nacional/étnica/racial, puertorriqueña, ni siquiera caribeña. Todas las identidades anteriores se dan por sentado o se les da la vista larga.

Lo que sí impera en cada cuento son mujeres “bregando, ” por utilizar el consuetudinario término boricua estudiado por Arcadio Díaz Quiñones en El arte de bregar: Ensayos (San Juan: Ediciones Callejón, 2000). Según Quiñones “el verbo bregar flota, sabio y divertido, en los múltiples escenarios de la vida puertorriqueña […] Las mujeres y los hombres emplean sin cesar ese verbo, con libertad e inteligencia. Los puertorriqueños están siempre en la brega, vulnerables, alertas. […] Bregar es, podría decirse, otro orden de saber, un difuso método sin alarde para navegar al vida cotidiana, donde todo es extremadamente precario, cambiante o violento … (19-20). Las mujeres de esta nueva literatura “bregan” de modo protagónico; no como trasfondo. Son mujeres que transitan, no sólo la esfera privada, sino también la esfera pública de Puerto Rico, el Caribe y otros escenarios indefinidos. La categoría “ciudadana” es fundamental para estos nuevos sujetos literarios. “El asunto es”—dice Santos Febres—“que la mujer aparece como agente en esos mundos. Los transita, los cambia, es cambiada por ellos, los explora, ya no desde la mera esfera de lo privado (como madre, esposa, amante, etc.) sino como cuidadana/marginal, profesional, viajera, etc. Desde otra mirada (4).

Esa “otra mirada” también incide en la mirada al mundo de la esfera privada, como ocurre en Carta al padre de Mara Negón, texto que establece diálogos diacrónicos y sincrónicos, con la generación del setenta y con Papí, novela de una estimulante escritora contemporánea de la República Dominicana: Rita Indiana Hernández. Inscrita la figura masculina como pretexto en la Carta al padre, la narrativa del cuento de Negrón explora a filiación de la hija lejos de la tensa y traumatizada inscripción de la figura masculina en la narrativa previa. Evita inscribir la figura masculina como un Ambrosio del cuento de Rosario Ferré: “Cuando las mujeres quieren a los hombres,” cuento en el que la sombra del temible hombre encauza una insospechada solidaridad femenina. Formada en París bajo el ala de Hélène Cixous, Negrón ha sido una importante diseminadora del feminismo de corte francés en la isla. Este padre que nos presenta es su propia re-elaboración caribeña del montaje teórico francés. El recuerdo del padre, ausente y añorado, es el fundamento del que se sirve la hija para explorar su goce (jouissance). “No he querido nunca alcanzarte, mi goce nace de la imposibilidad de alcanzarte, de la imposibilidad de no ver nunca ese rostro” (157). La ausencia de la figura paterna, tópico recurrente en las sociedades caribeñas contemporáneas, recibe como respuesta el goce de la hija, situación narrativa que diverge del tono de Papí de Rita Indiana Hernández (San Juan: Ediciones Vértigo, 2005). El texto de Hernández explaya la furia de una juventud desquiciada por las calles de Santo Domingo. Todo tipo de sostén económico recibe la narradora de su papi, un “PostPater” (término de Manuel Clavell Carrasquillo) criado en los fangales, a la sombra del paternalismo de Balaguer. Luego de “superarse” vive una vida de cuarentón nuevo rico entre el barrio y Miami, totalmente a espaldas de su hija. Papí es el furibundo reclamo de la hija ante el abandono del padre. En ese sentido, Rita Indiana estaría más próxima a las narradoras puertorriqueñas del setenta, a pesar de sus ambientes localizados en un postmoderno y caribeño siglo veintiuno. Lejos de la furia, el reclamo y el descontrol, la Carta al padre de Mara Negrón presenta un goce pausado en un mundo interior que ocupa cada oración, toda la página. El padre es tan sólo el pretexto.

El texto de Mara Negrón—quizás el que más se regodea en el concepto género—es sólo un ejemplo de la conversaciones que entabla esta antología, pero los registros de los otros cuentos son anchos y ajenos. Se trabaja el texto social, el de fantasía, el intimista, el erótico, la recreación histórica. Los tonos son tan diversos como las escritoras. El andamiaje narrativo también. Sin embargo, ninguno de estos cuentos es contestatario. No buscan instaurar “justicia poética” (5). Simplemente exploran la condición de ser mujer en el mundo; ser escritora en el mundo globalizado pero aún profundamente patriarcal en el cual vivimos. La visión de ese gran mundo globalizado narrado, visto desde el minúsculo punto cartográfico que supone esta isla caribeña, hechiza a las escritoras antologadas y a quien las agrupa. “[L]as razones por las cuales me interesa presentar a estas escritoras—dice Santos Febres en el antologario— “es que se adentran en una cultura de la globalización desde Puerto Rico” (3).

Los textos de estas doce escritoras son, según la propuesta de Santos-Febres, las espinas de un erizo que, “a ritmos diferentes, se van hundiendo en la piel despreocupada de la literatura puertorriqueña”. Con este título, Santos-Febres inscribe y reta la tradición cultural de la femme fatale y la vagina dentata, otorgándole un giro caribeño y reivindicativo a una imagen trillada, irritante e, incluso, no procesable. Los erizos, al igual que las escritoras de esta antología, son criaturas que merodean el ambiente, pero que al sentirse amenazadas son capaces de enrollarse sobre sí mismas y formar una bola púas. La casa de la escritura le abre el camino a la inmensa y globalizada intemperie que habitan los erizos, esas criaturas que entran en contacto dejándose sentir.

Spring 2008, Volume VII, Number 3

Carmen Oquendo-Villar (www.oquendovillar.com) is a Puerto Rican scholar and artist. She obtained her PhD from Harvard. Her work revolves around issues of media, performance and politics, film and visual culture, as well as gender and sexuality.

Carmen Oquendo-Villar (www.oquendovillar.com) es una artista y erudita puertorriqueña. Obtuvo su doctorado en Harvard. Su trabajo gira en torno a temas de medios, performance y política, cine y cultura visual, así como género y sexualidad.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Puerto Rico

Long, long ago before I ever saw the skyscrapers of Caracas, long before I ever fished for cachama in Barinas with Pedro and Aída, long before I ever dreamed of ReVista, let alone an issue on Venezuela, I heard a song.

God Needs No Passport

For a practicing Buddhist, my first Mass attendance at St. Ambrose two years ago was a memorable event. I had spent the earlier part of the day visiting…

Blood of Brothers: Life and War in Nicaragua

Stephen Kinzer, New York Times Bureau Chief in Nicaragua for most of the war years, pauses in his compelling account of the war and its politics to explain the Socratic method needed to give…