Linguistic trajectories of Mexican-American transnational students

Irelda (not her real name) is a twenty-two-year-old Mexican-born college student, who has lived in both the United States and Mexico. Her life has been marked by interruptions, both culturally and in terms of language, as she crosses borders.

Irelda’s mother decided to go to the United States for the first time because she says that life was untenable for her as a single mother in her small town. She had older siblings in the United States, so she followed their footsteps, leaving her two small children with their grandmother. Irelda’s mother and father met while crossing the border.

The first of a series of cultural and linguistic interruptions occurred after Irelda’s conception in the context of immigration. “I was made in California, and I was supposed to be born in California,” Irelda says. In the end however, she was born in Mexico. Her mother made the decision to go back to Mexico to have her child. Irelda was two years old by the time her father, who had remained in the United States, raised the money to send for her mother, her and her two half-brothers.

In the language of our field, we might say that the development of Irelda’s communicative repertoire over the course of her life has been shaped by a discontinuous linguistic trajectory.

Irelda’s linguistic development began in Spanish as a toddler, but her communicative repertoire developed in both Spanish and English because she was raised in a Spanish-speaking family in the United States. When the recession hit in 2008, life became increasingly difficult for her family. When she was thirteen, her mother and siblings moved back to Mexico. Irelda didn’t remember anything about the country. She returned (although it didn’t feel to her like a return) to a town overwhelmed with drug-related violence. The violence even cut short her school year. Over the next few years she says she did not learn much and she thinks her lack of Spanish resources curtailed any progress she should have made in those years. “…I had a hard time with Spanish, like, I knew Spanish, I could communicate somehow with them, but I didn’t understand anything from school. Vocabulary I needed for the school I didn’t understand it. … And so, I kind of just settled.” When she started school in Mexico, Irelda found that the Spanish she had developed and used at home was not the same as what she needed to develop for success in an academic environment. Neither her nor her mother report any support or strategies to help Irelda develop academic literacy skills in Spanish.

In high school, her opportunities to maintain her English were diminished because she was exiled from English classes for “knowing too much.” Like many students with educational experiences in the United States, there was little to no opportunity available within the school system for improving her English because she was perceived as a threat to the English teacher.

When she started college, she did not feel academically strong in English or Spanish and she suffered. “Because I didn’t know enough Spanish, but I was forgetting my English, so I struggled,” she says. Now that she has almost graduated college she uses English at work all day in her work as an English-language teacher, six days a week, and sometimes she forgets to switch to Spanish to speak to her mother when she gets home.

Schools, families and teachers in Mexico face a complex series of struggles because of these transnational experiences of youth and young adults with academic experiences in more than one country. The lived experience of these students is often a series of discontinuous and thus disjointed events and negotiations that create complex linguistic trajectories. Students’ life histories in the context of families who travel back and forth between countries illustrate the fragmented development of their linguistic repertoires. They highlight the intricacies of how families respond to the implicit and explicit language policies they face over the course of their lives.

Research into multilingualism has recently begun to dismantle what many have called a monolingual bias in second language studies, which assumes that the initial norm for most people is monolingualism. Recognition of dynamic multilingual experiences, like those we recount here, has led to more research into the development of mobile linguistic resources and the trajectories that bring them into being. Linguistic resources include all the ways we make meaning and communicate without necessarily assigning these resources to particular languages. In our work, we do not focus on how Spanish speakers acquire English and then Spanish as they move from Mexico to the United States and back again. Instead, we use linguistic biographies to look into how families navigate and form ideologies, practices and language management in the development of their linguistic repertoires as they move between often monolingual ideological spaces.

The roots of U.S.-Mexican immigration can be found in the political and economic relationship between the two countries which has contributed to great waves of migration over the course of their histories. Historically, these waves were perceived to be from Mexico to the United States, recently however, more people are returning to Mexico than those who are going to live in the United States. This means that Mexico has to confront a new identity as a country that receives immigrants because many who arrive were born in the United States. The reason for this return is complex: many points to stricter immigration policies in several states, deportations and the 2007 economic crisis as reasons for this sharp uptick. Based on data from various sources, it is estimated that more than 2 million people returned from the U.S. to Mexico in the 2005–2010 period (https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2012/04/23/ii-migration-between-the…). Although these transnational families have been the focus of research from economic, social and cultural perspectives, there has yet to be much focus on their linguistic experiences from the perspective of “return”. These families have brought with them complex language realities originated in their lived experiences in both countries.

While we consider each family member’s individual linguistic experience, our focus has been on the children. How have they have faced these experiences? What kind of language decisions have families and children in particular been confronted with? How have these experiences and decisions contributed to the development of their linguistic resources?

Although some might describe Irelda as bilingual, she did not accept that label for herself when we first met her. Her experiences as an immigrant in the United States and a returnee in Mexico mean her linguistic reality is complex. Although she initially would not call herself bilingual, she recognizes that her linguistic competencies vary and have developed differently over the course of her life. Her initial language development occurred in oral vernacular Spanish, the language of her family. When she started school in the United States, she began to develop oral and literacy skills in English. “…it was mainly English because my mom wanted us to learn English. My brothers and I, um, but I did learn like the basic Spanish…” Although her brothers had previous educational experiences Mexico and had developed reading and writing skills in Spanish before moving to the United States, Irelda’s literacy development in Spanish depended on her mother who had been given an elementary textbook and used it to teach basic literacy in Spanish to Irelda.

Thus, before another interruption in her linguistic trajectory with her return to Mexico, she had developed resources in oral vernacular and minimal literacy in Spanish as well as resources in English oral vernaculars, oral standard and literacy. This meant that as a teenager in Mexico, she had to work to develop Spanish oral standard and literacy resources. At that time, she also began to experience that both her spoken and written English was beginning to get rusty because she was only using English with her brother, she reports. In college, at the Autonomous University of Nayarit, as she completed her degree in Applied Linguistics, she developed her linguistic repertoire improving oral standard and literacy resources for both languages. Now in a professional environment as an English teacher, her English oral standard and literacy resources have gained the upper hand since use of Spanish is not allowed in any form at her place of work.

Our work with the linguistic biographies of transnational students and their families has helped us to connect the micro to the macro in language planning and policy. One of the questions our research hopes to look at is what families and schools can do to make this kind of discontinuity less fractured for transnational students. By understanding the linguistic trajectory of each of these students we hope to build the foundations for developing policy actions in benefit of multilingual development.

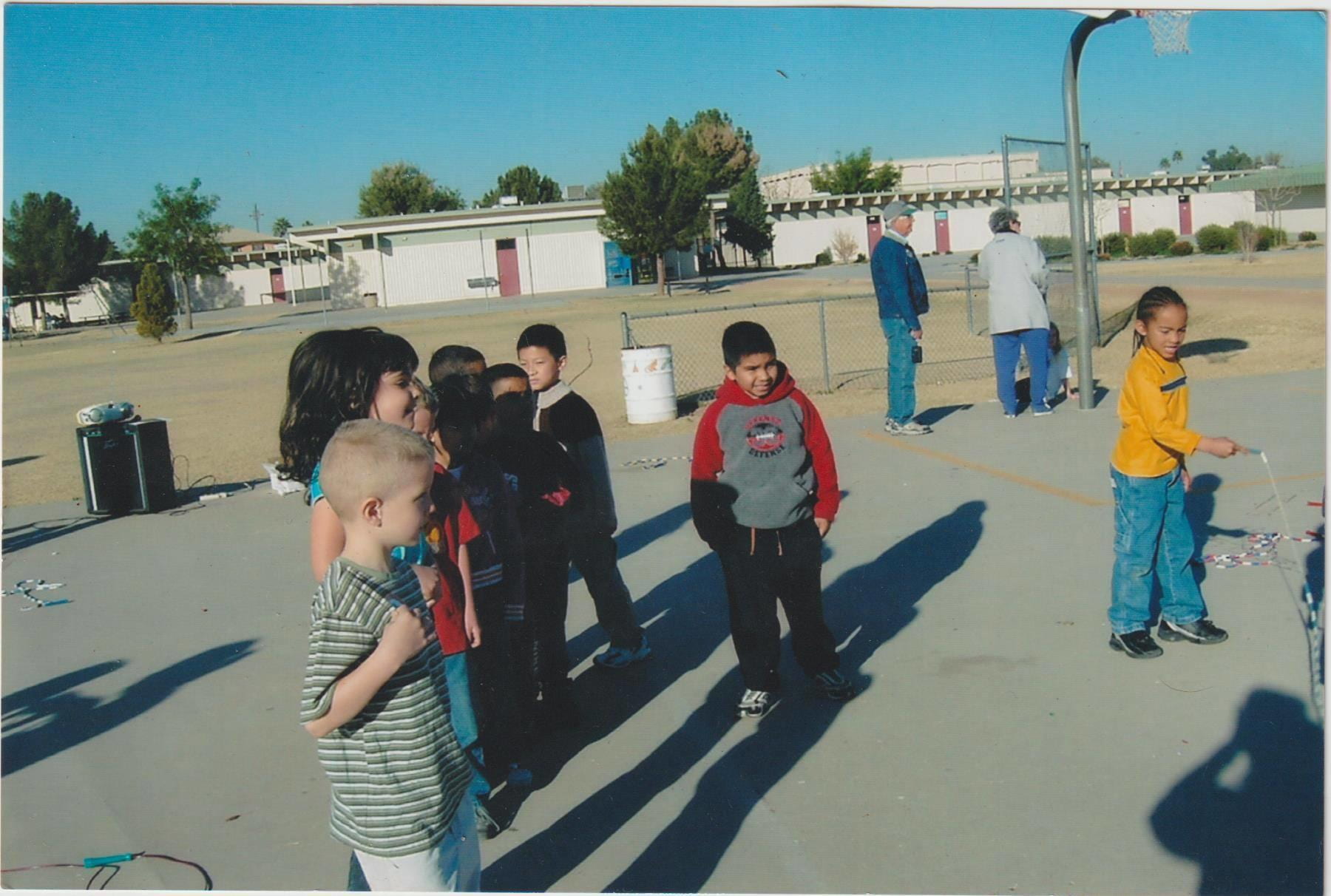

Another of the transnational students we talked to, David, was born in Phoenix, Arizona, and went to kindergarten and elementary school in Glendale. He grew up developing both Spanish and English as part of his linguistic repertoire as an American born into a Spanish-speaking family. “I spoke Spanish…, I learned English [at school] interacting, playing with others… Sometimes they [other students] repeated words, then I used to repeat and the next months I was able to speak English.”. At home he watched cartoons in English because he did not have access to television programs in Spanish.

When his mother decided to move back to Mexico it was a whole new world; one which was familiar to his mother but completely unfamiliar to him. One of the most difficult challenges was the change represented by the Mexican education system. English had always been the language used at school but now he had to focus on developing his Spanish skills in reading and writing, leaving less room for English. In Mexico he did not even use English at home. His younger brother was still very young when they came to Mexico and after a few months he started to forget the language. “When I came here to Mexico I didn’t know how to read and write [in Spanish]. It was hard. I really loved my English classes because it was the language I was able to handle it because was easier for me. I was learning [how to read and write in] Spanish when the teacher wrote on the board because when she talked I didn’t understand. I tried, but I couldn’t get it”. He adds that he thought he knew Spanish but in Mexico he realized he did not “my parents didn’t teach me,” David said.

Like Irelda, he was faced with the realization that his resources in Spanish were not adequate for the educational context in Mexico. He found that his literacy development in Spanish had never been attended to and now that he was expected to integrate into a new monolingual school system, he did not have the skills he thought he did. Like with Irelda, the consequences could be seen in his educational progress.

During his first school year in Mexico, David reports that he did not learn anything. The year after, his family decided to change his school. “In 6th grade I had to move to other school. I lived a change there. My classmates didn’t laugh at me. The teacher helped me to improve Spanish pronunciation. He corrected me how to produce sounds and how to write well. He used pronunciation exercises in order to improve the way I produced words. He was a very good teacher.” The teacher was open to David’s experience with languages, positive about bilingualism and asked some of his classmates to help him to improve his Spanish skills while he helped them with the English class. The discontinuities in development that David experienced were partly addressed through the actions of his teacher

Unlike with Irelda however, David and his family report receiving support with his developing linguistic resources at school. This kind of support from teachers tends to be an individual teacher’s initiative. There is no institutional detection of needs, or directive to even recognize the challenges these students face. Likewise, for neither David nor Irelda is there mention in their biographies of any additional educational opportunities available for either English or Spanish development outside of the institutional context. Irelda’s older siblings provided opportunities for continued use of English at home but because David’s younger brother hadn’t had the same educational experiences to support English development before coming to Mexico, the opportunities for sibling support strategies were not likewise available to them.

David and Irelda’s trajectories share many similarities with Carol’s (not her real name). Carol is twenty-one years old. Her family went to live in California when she was one year old, and her sister was born there. After ten years in the United States, they came back to Mexico. “…I didn’t even finish fifth grade in the US, when I came here in Mexico, I finished it here, but I didn’t know anything of Spanish. People thought I didn’t understand, but I have always understood what they told me, but I didn’t know how to answer in Spanish.” Carol’s parents knew a little English, and although they used Spanish to communicate with their daughters, they did not ask them to speak it which meant that Spanish was a receptive resource for the sisters. Although they understood Spanish, they weren’t used to using it to communicate with others, especially at school since all their education had been only in English. Carol was not only entering a new space and a new school when she came back to Mexico, the subjects at school were different, the way those subjects were taught was different, and she could not write or read in Spanish. “I didn’t know how to read [in Spanish] until I got to middle school. I didn’t read, like, a little bit. In middle school was like I really learnt.” Like with David and Irelda, for Carol, school meant sudden recognition of language disfluencies and the challenge of developing new Spanish literacy resources in her teen years.

The irony was that when she was still in the United States, Carol had been excited to start middle school because she was going to be able to take a foreign language class like French or German. Here in Mexico however the only foreign language option available was English, the language she had been speaking since she was 5. Opportunities for maintaining development of her English oral standard and literacy was reduced to a 50-minute class that she was not allowed to take because she already spoke English. Like in Irelda’s case, when Carol’s English teacher found out she had grown up in the United States, he told her he would give her a 10 but that she should not come to class because she would be a distraction.

Carol says it was raining hard one day, so she was given permission to stay inside the English classroom instead of leaving and finding something else to do. She put on her headphones, kept her head down and worked on her homework for another class. At some point she realized her teacher was asking her a question, so she took off her headphones to find out what her English teacher wanted. Over the next few minutes she says she felt the shame of not being able to explain the grammatical structure of present perfect. Her English teacher berated her “You should know this.” “Don’t you speak perfect English?” “How can you speak English and not know how to answer this?”

The discontinuities in the development of these transnational students’ repertoires create challenges related to beliefs about what linguistic knowledge one should have and what practices are acceptable. In her English class, Carol’s knowledge of English was deemed insufficient for the lack of metalinguistic knowledge valued in an English as a foreign language speaker, while it was likewise too native-like or fluent to be accepted into the class. Growing up in the United States, David thought he knew Spanish but discovered otherwise when he started school in Mexico and realized he had never learned to read or write in Spanish. Irelda says she thought she was smart in the United States, but that perception changed when she got to Mexico. “When we lived in the United States, I was like really smart, … I would always be like doing my homework and stuff. But then when I got here … in middle school and I didn’t do anything. I kind of just went downhill.”

From these linguistic biographies, we can see that one of the challenges transnational students face is how to advance in the face of discontinuous development of their linguistic repertoires. To varying degrees, when confronted with the Mexican educational context they all lacked the Spanish literacy resources expected of them. Their trajectories also point towards the various adaptation strategies employed by the different families and students. While Irelda’s mother made early attempts to address literacy development in Spanish, David’s teacher proved to be an invaluable resource once he arrived in Mexico and Carol’s parents provided extracurricular support with homework. Strategies to maintain English resources once in Mexico have been mainly found in sibling interactions, use of globalized media and personal motivations.

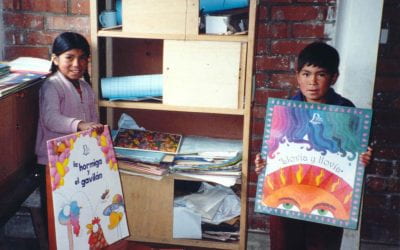

Collecting the linguistic biographies of transnational students have helped us understand how the different elements of an individual linguistic repertoire are developed. Literacy skills are often believed to be the prerogative of schools and thus for the transnational families we have worked with, we do not often see indications that families consider these to be skills that can also be developed within the scope of the family or home environment. In addition, many transnational families in the Mexican context do not have the opportunities to continue to develop English literacy through access to high-quality English classes outside of the public educational context. We have seen with the students we have worked with that instead they focus on maintaining the informal English resources that make up their repertoires. The choices that families and students are making about which resources to develop and maintain are often shaped by the opportunities that they have.

Likewise, the importance of developing literacy in both languages in the host country for transnational students can be seen from these linguistic autobiographies. Although transnational families may not have predetermined ideas about remaining in the host country, in the absence of dual development, the struggles these children experienced developing literacy upon arrival in Mexico are real.

Our research into the complex linguistic trajectories of these students show that over the course of a life, resources develop in an often discontinuous fashion and that an approach that accepts this reality is intrinsic to facing the challenges of dismantling the monolingual bias in schools and society.

Dana Nelson is a professor at the Universidad Autonoma de Nayarit. Her research focuses on indigenous language reclamation, educational linguistics, language policy and multilingualism.

Jesahe Herrera Ruano is a professor at the Universidad Autonoma de Nayarit. Her research interests lie in language policy, language ideology and sociolinguistics of globalization.

Jesus Helbert Karim Zepeda Huerta is a professor at the Universidad Autonoma de Nayarit. He is interested on ESL, EFL, applied linguistics, material design and language policy.

Related Articles

Ghosts of Sheridan Circle

Targeted killing of political enemies—assassinations—is thankfully rare in the United States. The most famous such assassination occurred in Washington, DC. And it was committed by a close ally of the United States. In September 1976, Chile’s Pinochet dictatorship…

Bilingualism: Editor’s Letter

It was snowing heavily in New York. It didn’t matter much to me. I was in sunny Santo Domingo with my New York Dominican neighbors on the Christmas break from school. I learned Spanish from them and also at the local bodega, where the shop owner insisted I ask…

Two Wixaritari Communities

English + Español

I first arrived in the wixárika (huichol) zone north of Jalisco, Mexico, in 1998. The communities didn’t have electricity then, and it was really hard to get there because the roads were simply…