Afro-Roots and Mozart Too

Building Foundations for Jazz and Beyond

I discovered jazz at 13 in my musical household in Cuba when my brother brought home a cassette tape of Chick Corea’s record “Friends,” and ever since I have been obsessed with the genre. There was no such thing as jazz in the conservatory where I was already studying, not even a whisper from our teachers that this American form existed. I began to find out everything I could about jazz. I traveled to the National Library in Camagüey to see what I could learn, and then discovered two radio stations in Cuba that broadcast jazz, so I began teaching myself by transcribing what I heard on cassettes and the radio.

By then at the conservatory I had chosen the saxophone as my major instrument and the piano as my secondary instrument. I loved the freedom that jazz would allow me as well as how I could use my instrument. What jazz offered me was complete ownership of what I was going to write and play. I wrote my first jazz composition when I was fifteen; I was very proud of it and hoped that my future would be in that musical genre. I continued to study both jazz and Cuban popular music and was greatly influenced by saxophonists John Coltrane and Wayne Shorter as well as by the popular Cuban group Irakere with their multi-genre styles of playing. When I graduated with my Master’s from Havana’s National School for the Arts (ENA) at nineteen, I began touring and playing with the famous “nueva trova” singer and composer Silvio Rodriguez.

I formed my first jazz group, Columna B, in the 90s and began playing in the clubs in Havana. In 1993 a board member of the Stanford Jazz Workshop heard my group and made it possible for me to travel to Stanford University in 1995 to play and teach in the United States.

My musical journey had begun even earlier than that discovery of jazz at 13.

My father’s orchestra, Maravilla de Florida, was one of the most important charanga orchestras in Cuba. Charanga, the most popular music in the dance halls of the island, was created by the creoles, and since the beginning featured mixed-race ensembles and symbols of a new cultural identity.

It was a foregone conclusion that I would become a musician, and so my parents engaged a teacher and I began learning to play the violin at age five. When I was old enough they sent me to the conservatory. In the conservatory the teachers were from Russia and the then-Eastern Block countries, and we studied the Western classical cannon exclusively. Monday through Friday I studied Western classical music, and on the weekends I continued to learn Cuban popular music at home, as well as the traditions that were part of the African lineage of my family. Afro-Cuban and Afro-Haitian musical traditions are rich on both sides of my family. I started going to Lukumi and Haitian vodou ceremonies when I was a child. At these religious ceremonies, I would learn chants and rhythmic patterns, as well as how to play several traditional instruments. This was something I couldn’t talk to my friends at school about, because at the time there was a stigma associated with African cultural traditions.

I am conscious of being Afro-Cuban, because in Cuba it’s difficult to escape that fact. Racism is present in the general culture, but since my parents never spoke about race in a divisive way at home, and given that schools in Cuba are racially mixed, that never got in the way of learning music.

Most Cuban people don’t see music in terms of black and white, and the Cuban cultural mixture is from both Africa and Europe. This marriage is so deep and strong that the elements are hard to separate. Music has served as a unifying force, bringing Cuban people together in concert halls and on the dance floor.

MY CREATIVE PROCESS IS NOT RANDOM

Growing up in Cuba in a musical family I understood that music feels fresh and spontaneous to the listener—after hours of practice by performers to master our instruments, and rehearsals to master the genre we want to play. I have always been a questioner, even as a child. “Why, where, and how” were my first responses to being asked to learn anything. This curiosity made research feel like a natural part of the creative process as I grew up, and is critical to my work today.

Those questions made me curious about my Afro roots. Like Bartok and Kodaly before me who collected Hungarian folksongs and used them in their compositions, I draw from Afro-Cuban heritage, jazz and classical music in my compositions. There are many cultural references in my music in both obvious and subtle ways, in the instrumentation, melodies, rhythms, harmonies, chants and the use of specific composition techniques. I see composition as an independent art form within music, which requires focused study in order to learn both the acoustic principles behind the music as well as the composition process within the western classical musical tradition and the jazz canon. I believe this is where the legacy of creative musicians resides, and it is also where we re ect and explore the boundaries of music.

For a composer and improviser there are a lot of communalities within the creative process, and it is hard to become an artist with both a unique voice in your genre as well as a distinctive sound on your instrument. The art of improvisation demands that you work daily in an organized and methodical way.

The preparation for improvisation requires rigorous training, as you need to study the language, vocabulary and styles of those who preceded you in any genre in order to achieve mastery of your instrument as well as the theoretical and acoustic foundations of music. Only then can you start getting ready to make your own musical contributions and craft your personal sound and style. The goal is to train our mind and senses to quickly react in any given musical circumstance or situation. Improvisation is a form of composition that happens in real time in the context of band members interacting and interplaying with each other utilizing various musical themes or ideas.

MY PROJECTS ARE DRIVEN BY A FOCUS

Much of my current research is stimulated by a new project and therefore has the goal of informing specific compositions, CD or a unique performance. My “New Throned King” project is the result of my ongoing research on the Arará tradition, and is a good example of how I marry African and jazz traditions and contemporary aesthetics.

“Okónkolo,” a project with the Bohemian Trio, is a unique opportunity to grow and expand on my classical music training through the chamber music format. The trio’s repertoire focuses on composers from the Americas—North and South—to reflect the multitude of musical traditions from these continents.

My latest musical adventure has been with the“Ancestral Memories” quartet, a project that was the result of a grant from the Mid-Atlantic Foundation’s French-American jazz exchange program that provides resources for an American and a French jazz composer to work together. French pianist and composer Baptiste Trotignon and I set out to research the musical traditions that came out of French former colonies, including Martinique, Guadeloupe, Haiti, and New Orleans, as well as Cuba, to create a body of compositions that reflects the cultural narratives of the Caribbean. Included in the recording that came out of this project were Yunior Terry on bass and Jeff “Tain” Watts on drums. We are continuing to tour as part of this project in the United States and in France.

MY TEACHING REFLECTS AN ATTENTION TO CONTEXT

As a professor I bring my personal knowledge and approach to research to the students at Harvard in both my West African Musical Tradition and Foundation of Modern Jazz courses. Students get the opportunity to learn the chants, melodies and rhythmic patterns from the African Diaspora and the social context in which these musical traditions were created and preserved. In the Foundation of Modern Jazz course students learn the language and vocabulary of the jazz canon within the social and historical context of the United States. I hope to inspire my students to dig deeper into cultural traditions and gain a more complete understanding of how culture and history are re ected in music.

When I came to this country I met and toured with the saxophonist Steve Coleman, whose musical trajectory inspired me to continue to look back into my own culture and rethink spirituality in the context of Afro-Cuban music and American jazz as I teach, play and make my contribution to the current musical conversation.

Winter 2018, Volume XVII, Number 2

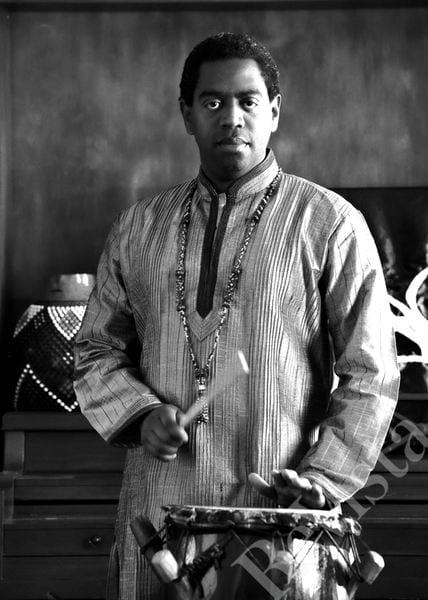

Yosvany Terry is a senior lecturer on music at Harvard and director of the Harvard Jazz Band.

Related Articles

Afro-Latin Americans: Editor’s Letter

My dear friend and photographer Richard Cross (R.I.P.) introduced me to the unexpected world of San Basilio de Palenque in Colombia in 1977. He was then working closely with Colombian anthropologist Nina de Friedemann, and I’d been called upon by Sports Illustrated to…

Witches, Wives, Secretaries and Black Feminists

The issue of gender has been front and center for me, both as a subject of my fieldwork on black politics in Latin America, and how I conducted that research, particularly in how I…

Compañeros En Salud

English + Español

I have lived in non-indigenous rural Chiapas in southern Mexico since 2013, working with Compañeros En Salud (CES)—a Harvard af liated non-profit organization that partnered with…