Zika and Abortion

Reproductive Justice in El Salvador

DON’T GET PREGNANT

That was the essence of the recommendation the Ministry of Health in El Salvador made on January 21.

The statement that Salvadoran women should plan to “avoid getting pregnant this year and next” was issued in response to the rapidly spreading Zika virus, which experts believe may cause devastating neurological defects in the fetuses of pregnant women.

The unprecedented call for a two-year, nation-wide moratorium on births quickly garnered international attention, including front-page coverage on The New York Times (http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/26/world/americas/el-salvadors-advice-on-…). Progressive news outlets responded with disbelief, calling the recommendation “outrageous” and “offensive to women.” How could the Salvadoran state expect women to simply stop getting pregnant when access to family planning is “scarce,” Catholic teachings reject the use of contraception, and rape is far too common? And what would the state offer already pregnant women now infected with Zika? Would they not consider relaxing the state’s absolute prohibition on all abortion?

To date, Salvadoran public opinion has been largely opposed to permitting abortions in cases of fetal anomalies, even when the fetus will not survive after birth. Yet as the very real possibility of raising a child with severe developmental delays becomes newly salient to thousands of Salvadorans dreaming of parenthood, and as the Salvadoran state grapples with questions of how it will care for a generation of Zika babies given its limited national resources, some activists have posited that this tragedy might be enough to change both public opinion and political will toward a loosening of abortion restrictions in El Salvador.

However, conservative pundits also met the government’s call to not get pregnant with indignation, asking why the Salvadoran government would focus on preventing pregnancies rather than on killing the mosquito responsible for the virus’ spread, condemning pro-choice groups for taking advantage of a regional tragedy to pursue their political agenda, and professing the right to life of all unborn children, even those saddled with severe fetal anomalies due to Zika.

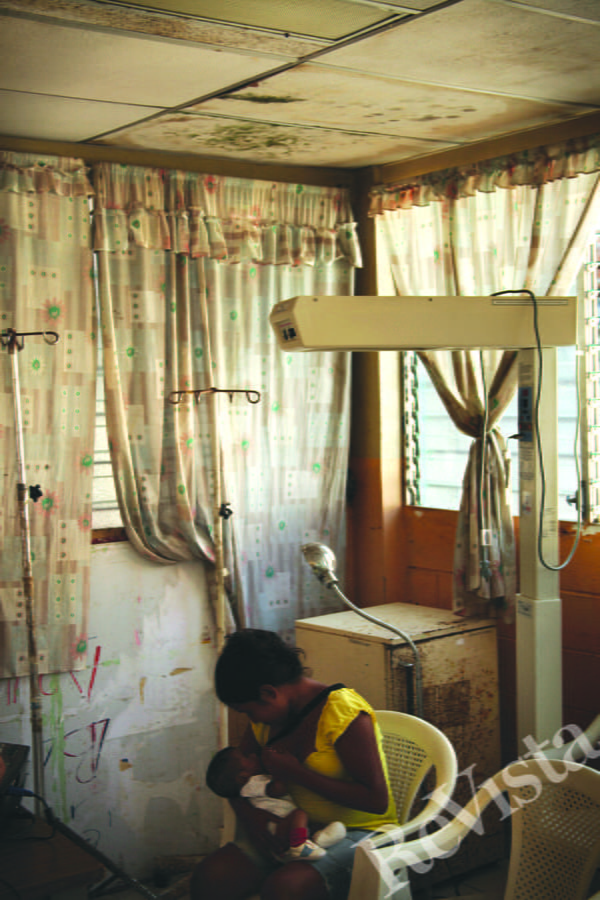

Catherin, de 13 años de edad, amamanta a su hijo mientras espera el inicio de la capacitación en maternidad en el Club de Madres Adolescentes en la Unidad de Salud del Puerto de La Libertad. Catherin ha pasado por varios problemas en su vida, a pesar de su corta edad. Fue criada únicamente por su madre. Viven en un cantón de La Libertad, en una casa donada por la organización Plan para familias de escasos recursos. Fue embarazada por un conductor de camiones, de 22 años, que le pidió hacer una prueba de ADN a Catherin porque al inicio no quería aceptar su paternidad. Fue expulsada de su casa por su madre que, con el tiempo, la perdonó. El padre del bebé nunca se ha responsabilizado por su hijo y no da dinero. Por orgullo, Catherine no lo demanda, tampoco su madre que como tutora tiene el derecho de hacerlo. En El Salvador, culturalemente, la seducción de menores de edad no se como algo natural y el incesto es un tema tabú.

It is far from the first time Salvadoran women’s bodies have been politicized on the international stage. Beginning in the 1990s, Pope John Paul II’s global crusade against abortion inspired a group of elite Salvadorans to launch a local pro-life campaign. At the time, abortion in El Salvador was allowed in only three limited circumstances: when a pregnancy endangered the life of the woman, when a pregnancy was the result of rape, or when a fetus had abnormalities incompatible with extrauterine life. The new pro-life movement, together with the Salvadoran Catholic Church, sought to make abortion illegal in every circumstance, even when a woman’s life was in danger. They achieved this goal in 1997, when the right-wing ARENA political party used its legislative majority to enshrine an absolute prohibition of abortion into the criminal code. The revised criminal code also increased the penalties for abortion, and created a new category of abortion crime, called “inducement,” which promised jail time for anyone who somehow facilitated a woman’s abortion. Under these new laws, Salvadoran doctors feared prosecution not only for performing life-saving abortions, but also for not reporting to the authorities any patient whom they suspected of undergoing the procedure.

In 1999, the pro-life movement cemented its position as a powerful player in national politics by securing a major legislative victory: the passage of a constitutional amendment that defines life as beginning at the very moment of conception. With the absolute ban now constitutionally protected, the Salvadoran pro-life activists turned their attention to the enforcement of anti-abortion laws. Salvadoran police heeded their call, and for the first time in recent history, Salvadoran women began to be arrested on suspicion of abortion. Most women found guilty of abortion received light sentences (community service, house arrest or time served during the trial), but a minority saw their initial charges of “abortion” upgraded to charges of “aggravated homicide.” These women, who in the majority of cases did not induce abortions but rather suffered from stillbirths, are currently serving thirty- and forty-year jail sentences. Perhaps unsurprisingly, nearly all women prosecuted for abortion and fetal homicide live in poverty; women of financial means are able to access safe abortions when needed or wanted, through private hospitals, and without risk of incarceration.

The debate over El Salvador’s absolute prohibition on abortion jumped into the international spotlight again in 2013, when a 22-year old woman known as “Beatriz” petitioned the Supreme Court for the procedure. At the time, Beatriz was only three months pregnant, and the mother of a young toddler. Beatriz had hoped for a second child, but she suffered from lupus, and the pregnancy was causing her kidneys to fail. Moreover, a series of ultrasounds confirmed that the fetus in her womb suffered from anencephaly, a birth defect in which large parts of the brain and skull are missing. The fetus would continue to grow and develop inside her uterus, but it could not survive outside of her body. The Health Minister, now serving under a left-wing FMLN president, publicly supported Beatriz’ request for what at the time would have been a safe, first trimester abortion of a non-viable fetus. Yet the Supreme Court refused to act, and doctors were expected to protect the life of both Beatriz and her fetus. Beatriz’ kidneys continued to fail. In her fifth month of pregnancy, she was hospitalized full time so that doctors could monitor her failing kidneys. She spent the next two months in a hospital bed, in pain, and away from her child, while the baby that she knew would die continued to grow in her stomach. It was not until the Interamerican Human Rights Court ordered the Salvadoran government to act that Beatriz, now at the start of her seventh month of pregnancy, was allowed to deliver early by cesarean section. Even at this point, she was denied the vaginal abortion that would have been safer for her precarious health than a cesarean surgery. The baby, born without a brain, died shortly after birth as expected.

The pro-life movement proclaimed the Beatriz case a victory: it ended with an induced, premature caesarean birth instead of a vaginal abortion. This, they argued, demonstrated how doctors can simultaneously prioritize the life of both the fetus and the mother. They had always acknowledged that the baby would not survive outside the womb, but they insisted that, for moral and legal reasons, the baby must be allowed to die naturally, at the hand of God, rather than be “killed” by abortion at the hand of people. They were largely dismissive of the pregnancy’s consequences to Beatriz’ life and health.

The pro-choice movement, which had accompanied Beatriz through the ordeal, was heartened by their sense that the case opened debate among Salvadorans about the powerful health risks imposed on women by the absolute abortion prohibition. However, they continue to lament the irreparable kidney damage suffered by Beatriz, which has to date resulted in constant pain and multiple medical treatments. Her life seems to have shortened by years.

As the tiny Aedes mosquito spreads the Zika virus across Latin America, Salvadorans may again be forced to wrestle with the consequences of their absolute abortion ban. Zika appears to be linked to microcephaly, a congenital condition that prevents fetal heads from developing to normal sizes. Although mild cases of microcephaly may have no effects besides the small head, the severe cases of microcephaly typically associated with Zika prevent fetal brains from developing appropriately, resulting in serious congenital problems including delayed or absent speech and physical movements, severely inhibited intellectual functions, difficulty swallowing, hearing loss and vision problems.

A twenty-five year history of policing poor women’s reproduction nevertheless challenges progressive hopes that Zika may result in a loosening of abortion restrictions. As the virus spreads, economically well-off women will likely access safe, clandestine abortions, but they will be able to do so quietly, privately, and without feeling any pressure to push the state for formal legal changes. Money buys reproductive choice in El Salvador. For women without financial means, decisions about their reproduction will likely remain in the hands of the state. What the state decides to do with its reproductive control of poor women’s bodies—whether it looks the other way as public health officials provide illegal but implicitly allowed abortion services to Zika-infected pregnant women, whether it allows poor women to be publicly demonized as moral and sexual deviants who “chose” to get pregnant despite the consequences, or whether it pushes for a legal, if temporary, increase in access to abortion—remains to be seen.

In many ways, the international media’s statements that contraception and sexual education are “scarce” in El Salvador belie reality. Family planning and contraception use are in fact widely available and widely accepted among Salvadoran mothers. This is clearly evidenced by dramatic drops in fertility over the past thirty years. Whereas a Salvadoran woman in the 1970s had an average of 6.3 births, this number had dropped to 3.9 in 1990, and to only 1.95 in 2014, well below population replacement rates (Population Reference Bureau, CIA World Fact Index).

The more important question is to whom contraception is accessible in El Salvador. Whereas the overall fertility rate has dropped a remarkable 42% between 2000 and 2014, the adolescent fertility rate dropped just 25% in the same time period (World Bank Development Indicators). And according to a Salvadoran newspaper, one out of every three pregnancies in El Salvador is to a girl younger than fifteen years old. (http://www.laprensagrafica.com/2014/10/10/30-de-los-embarazos-en-el-salv…). These statistics match well with my own research. The women I interview frequently report small family sizes, but with a gap of many years between the first and second child. Family structures like these result from the fact that women only gain access to contraception after having their first baby. Were young girls to enter health clinics or pharmacies seeking contraception, I was told, they would be denied contraception, and told instead that they should refrain from having sex. It is only after young girls give birth to their first child that the state enrolls them in family planning programs. The result is a low fertility rate, but an extraordinarily high rate of adolescent pregnancy.

Data points like these make clear that the Salvadorans most at risk for Zika-complications in pregnancies are teenage girls from poor families. Teenage pregnancies are already associated with a number of negative life course effects, including poor health, low education levels, low income levels, and greater likelihood of intra-familiar violence. If the thousands of teenage pregnancies that occur every year in El Salvador are now complicated by the Zika virus and related congenital anomalies, the life chances of an entire cohort of young women in El Salvador—and their children—could be severely and negatively affected.

In a nation where women with ectopic pregnancies struggle to get an abortion to prevent their fallopian tubes from exploding, where women are forced to carry to term pregnancies in which they know the baby will die at birth, and where women are jailed for up to 40 years for fetal “homicide,” any expansion in the abortion law would be welcomed as a powerful victory for human rights by the international community and local feminist groups. Yet if expansions in abortion access are brought about by a mosquito, rather than by a real engagement with the reality of women’s reproductive lives, it would be a fragile victory for “reproductive justice.”

Spring 2016, Volume XV, Number 3

Jocelyn Viterna is Associate Professor of Sociology at Harvard University, where she teaches and researches about gender and social movements in Latin America. Her award-winning book, Women in War was published in 2013 by the Oxford University Press

Related Articles

The Boy in the Photo

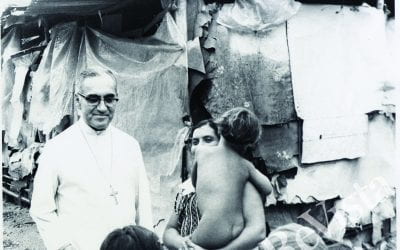

The mangy dogs strolled everywhere along the railroad track. I remembered dogs just like them from the long-ago day in La Chacra in 1979 with Archbishop Óscar Romero, just months before he was killed…

Beyond Polarization in 21st-century El Salvador

My father was a civil engineer who worked for the government during the civil war years. He specialized in roads and had to spend several days a month traveling to remote places in El Salvador. I was 10 in 1986, and I remember my mom asking my dad…

El Salvador: Editor’s Letter

I had forgotten how beautiful El Salvador is. The fragrance of ripening rose apples mixed with the tropical breeze. A mockingbird sang off in the distance. Flowers were everywhere: roses, orchids, sunflowers, bougainvillea and the creamy white izote flower…