Mining Challenges in Colombia’s El Choco

Locomotive or Steamroller?

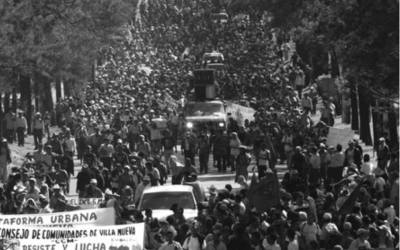

Some traditional artisanal miners in the Chocó region now seek to find gold in the areas of pits abandoned by machinery. Photo by Steve Cagan.

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos likes to promote extractive industries as the “locomotive” that will pull the country’s economy forward. His plan projects providing mining concessions for large-scale operations to multi-national mining corporations. In the northern Pacific department of El Chocó, that development means that large gold mines will replace the smaller mechanized operations that now exist, as well as the traditional artisanal miners.

This plan also pits the government against the smaller-scale mechanized miners, whom it accuses of running illegal operations. The operators fear they will lose everything because the government is trying to shut them down. The legal details can be mind-numbing.

The government is also in conflict with the local communities, which have special rights as Afro-Colombian or indigenous communities. However, the government’s position is that their territorial rights only apply to the soil, not the sub-soil. The people in the area, through their communities and organizations, express fears that Santos’ plan will mean the end of their rain forest, of the communities it has nurtured, and of their ability to make a living here.

Because of their concerns about this frightening prospect, the locals are making common cause with the current mechanized miners. This has provided a strong front of opposition to the multinationals. But some people see the alliance with the mechanized miners as a Faustian bargain. They argue that “the destruction that the multinationals will do in fifteen years, the current operators will do in thirty.”

The recent expansion of mechanized mining has produced a number of effects and consequences very different from those of traditional artisanal mining. The new practices have created divisions among the public; some individuals and communities see the mechanized mining as a great economic opportunity, while others see it as a threat to their forest and their way of life, and even have doubts about the economic benefits.

In September 2012, at a meeting during the Colombian bishops’ annual Week for Peace, community activists discussed the mining problem in Quibdó, the capital of El Chocó. A young Afro-Colombian activist, Eduardo, asked for the floor (note: community members’ names have been changed.)

“Everyone is upset about the government’s encouraging the transnational mining companies. And they are right to be upset. We are right to oppose that. But what about what we are doing right now? What about the damage we are doing to the forest by mechanized mining? What about the damage we are doing to our communities? What are we going to do about that?”

Most of the twenty or so people in the room agreed with him; only Juan Carlos, who works for one of the mechanized miners, disagreed. And even he did not feel he could strongly object.

This moment made clear how mining issues divide and unite people in local communities.

Just what are these issues and where did they come from?

El Chocó has always been an area of gold mining. Indigenous people mined gold there before the Conquest. The Spanish came to the Atrato River—the major artery in the area under discussion—because they knew there was gold there (and in the mistaken belief that it would provide a more direct route to Peru). They brought African slaves—mostly from other parts of the colony—who were the ancestors of today’s Afro-Colombian population, to work in the mines.

Some early mechanized gold-mining operations in El Chocó were playing out by mid-20th century; the gold was not sufficient to justify the costs.

Meanwhile, throughout the centuries, Afro and indigenous communities close to the gullies and rivers carried out traditional artisanal mining. This activity—what in the United States we call placer mining or panning for gold—is known in the area as bareque, and the men and women who engage in this artisanal mining are called barequeros/as or sometimes simply mineros/as.

The gold here is not in veins, but in small flakes scattered in the mud and soil below the surface. People pan all day to get much less than an ounce of gold; many tons of soil have to be turned over to find pounds of gold. In recent years, impelled by the sky-high price of gold, mechanized mining has come to this area, and with a vengeance. Hundreds of big backhoes have been brought in to open large pits in a search for the gold. The new mining operations represent a threat to the important, delicate rain forest environment, and also to traditional cultures, as people abandon the range of economic activities that have defined them culturally and have supported their families, to become full-time artisanal miners in the areas of the pits abandoned by the machinery. In other areas, the machinery destroys planting areas, kills fish, or otherwise interferes with such activities.

The mechanized mines do not directly hire many local people—a mine using two or three large backhoes to dig may have a crew of around twenty people, including mechanics and operators who come from other areas. But they do provide a special opportunity for panning for gold, as the owners allow people to mine in the areas where the machines have finished their work.

Since this work is physically less stressful than panning in the rivers (although it’s also more dangerous, as the pits are not very stable and collapses occur—an accident last year killed seven people, buried under tons of soil, but somehow these accidents seldom arise in the general conversation about mining), and because it is hoped that where the machines have worked there is more gold to be found, a good many people in El Chocó have become full-time miners.

The bareque has long been one of a range of family economic activities. Other activities have traditionally included planting (plantains, bananas, yucca, sugar cane, and a variety of fruits and vegetables) and keeping chickens and pigs, hunting and fishing, gathering fruit in the forest, and cutting wood—all primarily for consumption by the family.

Most of these activities were outside the money economy. A man forced by the violence of the civil conflict to leave his village along with his family remembered that “Back in the village, often we didn’t have a peso in our pockets. But we didn’t worry, because we knew our children would eat, and eat well.” Panning for gold and platinum (and to a lesser extent some surpluses from the other activities) provided the cash needed to acquire the things they could not produce—cloth, tools, and so on. And panning was a part-time activity.

“When I was a girl, my family lived on the Bebaramá River,” said María Eugenia. “This was a good place to mine—when the grown-ups went out to pan for gold, they found a lot. Still, they never did that all the time. We had our fincas; my parents and uncles and aunts planted crops to eat. And the men went to fish and hunt. The mining was important to us, but it wasn’t all we did.”

But things are changing. Recently, María Eugenia wrote to me: “…what do you think? I spent four days in the village where I was born, it was beautiful; it had been many years since I visited there. This community is in the Río Bebaramá…it is very organized, but as it is a mining community, they let themselves believe that [story] and many families have stopped producing [crops], now everything has to be brought there. For me this is very worrisome, because before they did manual mining and they also harvested, so when for some reason they didn’t go to mine, they weren’t hungry. Now they have let the heavy machines in and everything has changed.

I took advantage of being there and spoke with some relatives and advised them to reconsider the situation, but since right now they are feeling abundance, they did not pay attention to what I said.”

So one of the effects of the entry of mechanized mining is that in some places people are abandoning or sharply reducing their traditional range of economic activities and becoming full-time miners. (There is a parallel development in cutting down the tropical hardwood trees, traditionally an activity of a few weeks a year. Now it is the full-time occupation of men who use big chain saws provided by lumber dealers). Among other consequences of this change, younger people are not learning the skills that sustained their ancestors, and even themselves as children.

In the villages, some people tell me that the arrival of the machines in their villages has not affected their lives much, and others recount abrupt and dramatic changes. In part, this is because the experiences have varied widely from community to community, but the different versions of the story also clearly have to do with the plasticity of memory. The people who have shifted to full-time panning for gold will tell you, correctly, that they have more money than they have ever seen before. But it is also true that now they have to buy everything that they produced before. Despite their hopes, they don’t necessarily find much gold, especially in the abandoned pits (after all, the machines leave for a reason). A few years back, I became friendly with a couple of brothers-in-law who bought gold from the barequeros in a town on the Río Andágueda. They were considered by the miners to be more honest than the other buyers in town, and more generous in what they paid. (This was during the run-up of gold prices; I began to understand that part of their friendliness was that they wanted me to serve as their agent in the United States…) One day I asked one of them if the people working in the pit were going to be able to get themselves out of poverty by mining. “Never in their lives,” he said. “We are making some good money, but they can’t find enough gold for that.”

Without even talking about such “externalities” as stress, health and quality of life, are these people in better financial shape than before? They say “Yes.” María Eugenia and other local people I’ve interviewed say “No.” From what I can see, no one has examined this question in a rigorous way; the truth is, the answer remains unclear. Many articles, both scholarly and popular, have been published about mining policy, about the mechanized mining, and about the conflict between that practice and government plans, but so far I have found nothing about the direct financial and cultural effects on the artisanal miners. Inquiries among academic friends in the field found no one doing the research on this important and interesting subject.

The same argument remains unsettled for the economic effects of these changes on the communities as a whole. The organization of the mechanized miners claims that three-quarters of the new mines are locally owned, and that the communities are benefiting from the infusion of money. Many community activists dispute both the ownership figures and the supposed benefits. Once again, while work has been done on the effects on the national economy of medium-scale mining, I have found nothing on this topic.

While there may be grounds for serious disagreement about the economic consequences of mechanized mining, it is hard to avoid seeing the serious environmental consequences. Traditional activity in the rivers and streams—which still goes on—has barely any environmental impact. The amount of dirt that is turned over is very little, and this is primarily from the existing river or streambeds. Holes are not opened in the forest floor, or if they are, they are very small and shallow, and the forest can recover relatively quickly. The artisanal miners do not use mercury or cyanide, as mechanized miners do.

There is an intermediate kind of mining. Some of the artisanal miners are now using motorized pumps to move much more water, which allows them to get through a great deal more soil in a day. I witnessed a lively argument among a group of community activists: some felt that the damage done by the motobombas put them on the side of the big machines, while others felt the damage was minimal and that the forest and the streams could recover from the effects of their labor. I have seen how a stream, given one year’s rest from the motobombas, recovers its crystalline clarity. But have the flora and fauna recovered? It’s another open question.

Once I traveled with a couple of Basque video makers and the parish priest of Lloró to visit some of the mines and communities on the Andágueda River. The manager of one mechanized mine started arguing with the priest, saying, “You’re the priest who thinks he is the guardian of the environment!” He explained that even though it is true that they dig big pits, once the work is done, they cover them up and restore the forest. In fact, they are legally obliged to do that.

But it is equally true that even in the remote possibility that they would want to do it, it would be impossible. The many tons of dirt, silt, rocks that have been dumped into the gullies and rivers cannot be recovered to refill the pits. And even if they were recovered, the thin layer of tropical rainforest topsoil is gone. The forest cannot be restored.

The debris dumped into the streams and rivers also has its impact on them, of course. Coupled with the activity of thedragas—dredge boats that operate directly on the beds of the larger rivers—mining worsens the sedimentation and silting of the rivers. People in the communities complain of decreasing fish populations, and while some of this can be attributed to over-fishing and other sources of pollution, the mines are contributing to the problem. Meanwhile, as the mouths of the Atrato River become blocked with sediment, destructive flooding is becoming more common.

In order to turn the flakes of gold into manageable balls of metal, the mechanized miners rely on a method that goes back at least to ancient Rome. They mix the gold with mercury, which creates a solid aggregate. Then, to get rid of the mercury, they heat it, so that readily absorbable methyl mercury is given off into the atmosphere. In an interview, a doctor in a community health center said, “People come to me complaining that they have headaches and aching joints, that they are having trouble sleeping and concentrating. We know what the problem is; the levels of mercury in their blood are rising.”

But how serious a threat does mechanized mining pose to the forest as a whole? It’s hard to know, but we do know that in an area less than half the size of Ohio, there are now well over 800 of these pits, and the number is growing. Between the increasing destruction of the forest floor by the mines and the accelerating cutting of trees, the rain forest of El Chocó is moving towards an unknown tipping point, from which it will not be able to recover.

And now a much greater threat looms just over the horizon. The Colombian government is promoting much larger-scale mining by transnational corporations.

The communities—even those that support current mechanized practices—are nearly unanimous in their opposition to this development. At one community meeting, a well-known activist priest said, “This will not be a locomotive for us, but a steamroller!” The opposition is so strong and unified that when it became clear that some of the members of the junta directiva (the executive board) of the federation of Afro communities in the middle Atrato river basin had been bought off by a combination of international companies and government ministries, the organization’s “discipline committee” removed the entire junta from office.

The opposition to this new threat is being led by the organizations of mechanized miners. This is only logical. On the one hand, their economic interests are directly threatened by the government’s plans. And on the other hand, the government has been trying to remove them from the scene, claiming that their operations are illegal. The government’s position has a reasonable legal basis, but they have acted in a repressive manner towards these operators, turning them into martyrs and strengthening the support by the local people for the machine operators, who, they feel, have opened new economic horizons for them.

It’s a strange situation. The very people who have been doing so much damage to traditional culture and economy, and to the environment, are now able to present themselves as the defenders of traditional mining and the communities. And by allowing panning in the pits—at least in the areas they have finished working themselves—they have won the loyalty of many locals.

One day, I got into a conversation with the driver of the rapimoto (the motorcycle taxi) I was riding. He said, “I come from mining people, in Condoto [an important mining area in southern El Chocó]. My father was a miner. He worked and planned, got some property, got everything prepared, it all looked very good. Then those guys came and took the land from him.”

“But ‘those guys’ weren’t transnationals; they’re not doing that yet?”

“No, the men with the machines. These guys. They and we are going to be hurt by the transnationals, but that doesn’t excuse the way they act now.”

Which expressed the contradiction at the heart of the current resistance led by these “small” miners. The communities have to oppose the coming of the transnationals, and in some important ways that means making common cause with the current mechanized miners. But the result is lining up with people who themselves have already created a lot of problems.

It is this ironic and confusing turn of events that gives relevance and importance to Eduardo’s question.

Winter 2014, Volume XIII, Number 2

Steve Cagan is an independent documentary photographer who has lately focused on environmental issues and grassroots daily life on the Pacific Coast of Colombia. His latest work for ReVista was in the Winter 2013 issue on water. Together with artist Mary Kelsey, he has spearheaded a project intended to document the work and lives of grassroots miners—and the threats to their traditions—through photography, drawing, texts (by the people themselves) and more. He can be reached at steve@stevecagan.com The gold mining project website is elchocomining.net

Related Articles

Making a Difference: Building Blocks

Since the first, unplanned visit of a Brazilian entrepreneur in 2011 to Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child, a diverse group of professors, practitioners, civil society leaders and other committed individuals at Harvard and in Brazil have…

Travails of a Miner, VIP-style

English + Español

Sergio Sepúlveda is a Chilean miner with an enviable salary—equivalent to that earned by a university-educated professional. He owns a brand new Korean-made car, and every three years…

Indigenous People and Resistance to Mining Projects

English + Español

Latin America’s governments and its indigenous peoples are clashing over the issue of mining. Governments, motivated by economic growth, have established legal frameworks to attract foreign investments to extract mining resources. When those resources are located in…