About the Author

Romina Ruiz-Goiriena is an ALM candidate at Harvard Extension School in the field of journalism and a national correspondent for USA TODAY. Previously, she reported out of Central America for CNN and The Associated Press, covering issues such as migration, corruption and drug trafficking. She has also worked in Paris, Cuba, and Israel for France 24, El Mundo and Haaretz. Romina is fluent in English, Spanish, French and Hebrew.

Julia Gavarrete: The face of a new era of journalists in El Salvador

Fast-talking with kinky black hair, Gavarrete has an eye for stories that take a hard look at gender, machismo and politics in Central America. When my professor gave us the assignment of profiling a working journalist, I knew exactly who I wanted to pick.

As a journalist who worked in the region (and now going for my ALM in journalism at Harvard Extension School), I was curious about the new generation of journalists.

The crime scene in February evoked images from the bloody civil war that raged in El Salvador for three decades.

Gunmen opened fire on activists who were returning from a campaign event led by the opposition party, Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN). Two were killed and five others were injured.

It was the first political attack since the signing of the Peace Accords on Jan. 16, 1992. The assault quickly stirred concerns the country is entering a new era of intolerance as President Nayib Bukele’s party set to win the legislative election in a landslide.

Julia Gavarrete’s phone buzzes. A flurry of messages and pings. The 32-year-old reporter recently joined the ranks of Salvadoraninvestigative outlet El Faro after a decade working as a journalist.

This was her first weekend on the job.

Assigned to cover the FMLN party until the election set on Feb. 28, Gavarrete was walking into her house from having covered the rally earlier in the afternoon.

“Turns out, I had interviewed one of the people injured. I had their number in my phone,” says Gavarrete who landed the scoop, filing the first report in under an hour.

Fast-talking with kinky black hair, Gavarrete is one of the newest voices to come out of the Central American nation of six million people, with an eye for stories that take a hard look at gender, machismo and politics with aplomb.

Earlier this year, Gavarrete was a finalist for a team 2020 Gabo Award conferred by the namesake foundation created by Nobel Laureate Gabriel García Márquez. Gavarrete’s project “El Salvador’s Suicide Girls” with Univision revealed how violence was driving girls between 10 to 24 years old to take their own lives.

“She has this way of approaching stories that leaves the reader with a more nuanced understanding,” says Jonathan Blitzer, staff writer at The New Yorker, who has worked with Gavarrete on a few assignments over the years.

From oral tales to international bylines

Gavarrete was born in Chalatenango, a mountainous town in northern El Salvador nestled between the Tamulasco and Sumpul rivers. The city was damaged during clashes between government troops and guerilla fighters in the early 1980s almost a decade before she was born.

The area thrived with the cultivation of wheat, corn and coffee—Gavarrete is a self-confessed addict.

At the age of 14, she moved to the capital of San Salvador with her older brother but never forgot life in “el campo.” The fresh air. The greenery. The ability to roam freely.

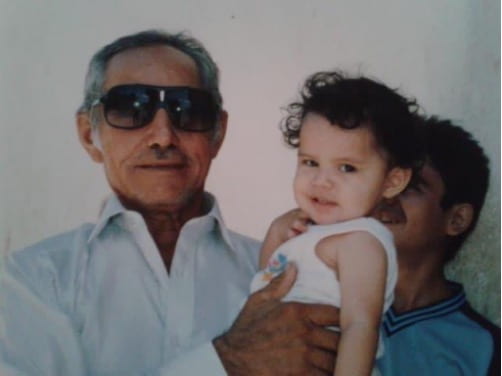

Another big influence in her life was her maternal grandfather, Martín Pineda. Gavarrete says the old farmer and merchant would tell stories that would enrapture her for hours.

Gavarrete with her grandfather and storyteller, Martín Pineda who inspired her to become a journalist.

“He had this way of crafting the perfect beginning, painting these larger-than-life characters,” she says, noting she never figured out if the tales were true or not. They had a certain fondness that inspired her to pursue storytelling, eventually leading her to journalism.

“It makes me happy to know that I followed my heart,” says Gavarrete, brushing her hair away from her face with her red-painted fingernails. “I feel as if I built this toolbox that determined the kind of journalist I aspire to be.”

After graduation with a communications degree from the Central American University José Simeón Cañas, she landed a cub reporter job for Salvadoran daily El Mundo with her longtime friend Xenia González.

The pair had met in college studying journalism and grew close while working on assignments, often into the wee hours of the night, while exchanging banter and Instagram food posts. Gavarrete has an insatiable sweet tooth when it comes to Salvadoran pastries. Her favorites: alfajores and sapor de arroz like her abuelo Martín.

González describes her best friend as someone caring and compassionate, able to make friends and sources feel comfortable instantly. She says Gavarrete has a big personality—in sharp contrast from her height of five feet—and a piercing gaze.

It’s impossible, Gonzalez says, to ignore when Gavarrete walks into a room.

“Well—that’s because you can hear the sound of her high heels click-clacking on the floor,” she says laughing.

For Gavarrete, the common denominator is looking for stories that “put a face to the facts,” that are able to humanize the most polarizing issues and those that reveal the human toll of living in El Salvador, ranked by the United Nations Office on Drug and Crime as one of the deadliest places in the world.

It was one of the things that Blitzer of The New Yorker noticed when he first worked with Gavarrete.

“She’s this kind of hurricane that is constantly working on so many stories and yet is always paying attention to you even if she’s weaving in-and-out of San Salvador traffic,” says Blitzer.

Working with Gavarrete always feels like you are hanging out with a friend, he says. Gavarrete knows where the best pupusas are and she might also take you on a random hike in the middle of the day if she’s killing time before an interview.

“I escape to the mountains or to the sea whenever I need to take a step back,” Gavarrete says.

Nature soothes her. Silence offers perspective. In the wilderness, Gavarrete connects to the part of herself that was care-free in “Chalate,” how locals refer to her hometown.

When in the city, she hits the pavement hard. Her work pays off.

After The New Yorker in 2015, she’s collaborated with other outlets like The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Elle, ProPublica and Univision.

Women have made all the difference

But it can be difficult to be a woman—especially a woman journalist in El Salvador. Sixty-seven percent of women have suffered some sort of violence including sexual assault, intimate partner violence, and incest, a national survey found.

In 2017, El Salvador became the country with the highest rate of femicide in Latin America with more than 10 killings for every 100,000 women. The nation also has some of the strictest anti-abortion laws in the continent, where women can face prison time for miscarriages.

Cecilia Menjivar, an expert on gender violence in El Salvador, writes: “Women are treated as property. And women must accept their role in the home, which includes demands for sex and physical abuse.”

And yet, most of the international reporting datelined out of El Salvador Gavarrete says deals almost exclusively with men: whether it’s about the 69,000 gang members or the young populist president.

Gavarrete sees her reporting as a way to challenge that narrative.

“There are so much more than gangs and Bukele,” says Gavarrete. “I have navigated the most complicated stories thanks to women in communities that have helped find ins, have vouched for me and have led to other women opening up to me—even when I am covering something gang-related.”

She also owes her career to veteran journalists that have mentored her, namely through the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF).

The D.C.-based organization contacted Gavarrete in 2016 to work supporting reporters parachuting in to do stories. In 2018, the foundation awarded her a small grant to follow the migrant caravan to Tijuana, Mexico. Many of them, too, encouraged Gavarrete to apply to the IWMF’s prestigious fellowship. She won in 2019.

“The foundation opened up the world to me,” says Gavarrete.

She was invited to trainings, international events and to speak at a dinner hosted by PBS’ Judy Woodruff. Gavarrete is a frequent panelist on high-level briefings in Washington D.C.

On one occasion Gavarrete’s dream came true: to work under her journalism idol, Pulitzer prize-winning reporter Ginger Thompson during the height of President Trump’s Family Separation Crisis in 2018.

“Ginger changed my whole approach,” says Gavarrete. “I had never seen someone take so much time, get close to a source, move slowly to capture a scene.”

Thompson, ProPublica’s chief of correspondents, describes the young reporter as courageous, smart, wired, with big ideas and someone who “didn’t seem cowed in any way by the challenges of the environment.”

“I knew she was going to be an important journalist. But she hadn’t gotten the platform she should have,” Thompson says, adding she was elated when she heard the news Gavarrete had joined El Faro. “They had been missing this voice.”

Thompson adds: “I hope women reporters in the region will now have more doors open to them to do this kind of work.”

While driving through the mountains in El Salvador, Gavarrete knew this might be her only chance to get invaluable advice from the veteran reporter.

“She said to me ‘can I just brainstorm with you some of the things I have on my mind?’” Thompson recalls.

In classic Gavarrete-fashion, the undeterred multi-tasker grilled Thompson for three hours straight.

“We spent a lot of time talking about what makes a good story. Why is that a story? Why isn’t that a story. Or if you want that to be a story then here’s the elements you need,” says Thompson. “I was almost serving like an editor.”

The two also bonded over hair products. When Thompson was flying down from New York, she asked her if she needed anything from the United States.

Gavarrete gasped with excitement over the phone.

“She tells me, ‘It’s a really stupid thing but I don’t have any products for curly hair down here. I don’t know if you know about those kinds of products.’ And I went, are you kidding? I am your girl,” says Thompson.

Threat of danger

Notoriety and hard-hitting accountability reporting from Latin America haven’t come without its challenges.

Local reporting like that of Gavarrete’s is more dangerous than war reporting, according to a UNESCO, which tracks violence against journalists worldwide.

Amid the COVID-19 outbreak and flurry of lockdown orders last July, unidentified individuals broke into Gavarrete’s apartment and stole her computer leaving behind everything else of value.

Her wallet, credit cards and money were on the table.

Gavarrete returned from covering a press conference at the Presidential Palace when she found her door ajar. She had been writing about government mismanagement, human rights violations and corruption.

She was shaken. Hours after the police came to check for prints and canvas neighbors, she had a panic attack around 2 a.m.

“I felt dizzy, nauseous, sick. I called a friend and was going to go to the hospital,” says Gavarrete recalling the events that night.

The Committee to Protect Journalists, an advocacy organization based in New York called on the Salvadoran government to open an investigation.

They have yet to receive a reply.

The incident changed Gavarrete’s working style; she started communicating with family via encrypted apps and installed cameras and metal bars outside her home.

It did nothing to dampen her determination regardless of the challenges she still may face.

Two months after the incident, her dad was diagnosed with colon cancer.

Gavarrete says she was overwhelmed. While many would have thrown in the towel and even taken time away from work, she says it has her refuge. Gavarrete leaned in.

Reporting, trying to manage the pressures of a new beat, exposure and family are taxing, she admits.

But Gavarrete says she finds solace in being able to tell stories, even the hardest ones to get through.

“If there is one thing working in this country has taught me is that I have to regenerate fast,” Gavarrete says.

And so, she does.

More Student Views

Of Salamanders and Spirits

I probably could’ve chosen a better day to visit the CIIDIR-IPN for the first time. It was the last week of September and the city had come to a full stop. Citizens barricaded the streets with tarps and plastic chairs, and protest banners covered the walls of the Edificio de Gobierno del Estado de Oaxaca, all demanding fair wages for the state’s educators. It was my first (but certainly not my last) encounter with the fierce political activism that Oaxaca is known for.

Public Universities in Peru

Visits to two public universities in Peru over the last two summers helped deepen my understanding of the system and explore some ideas for my own research. The first summer, I began visiting the National University of San Marcos (UNMSM) to learn about historical admissions processes and search for lists of applicants and admitted students. I wanted to identify those students and follow their educational, professional and political trajectories at one of the country’s most important universities. In the summer of 2025, I once again visited UNMSM in Lima and traveled to Cusco to visit the National University of San Antonio Abad del Cusco (UNSAAC). This time, I conducted interviews with professors and student representatives to learn about their experiences and perspectives on higher-education policies such as faculty salary reforms and the processes for the hiring and promotion of professors.

Post-Secondary Education Access in Peru

Over the summer, I visited four public schools in Peru located in two regions, about 1,200 miles apart from each other. I interviewed teachers, principals and high school juniors and seniors. I wanted to discover their perspectives on perceived opportunities and barriers for students to plan for and fulfill their higher education goals. I also interviewed the superintendent at each school district to learn about local initiatives aimed at decreasing barriers to higher education transition.