About the Author

Sam E. Valentine is a Master of Landscape Architecture candidate in his second and final year at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. With a decade of prior experience as a practicing landscape architect, his research focuses on community engagement within the process of design and expanding the discipline’s knowledge of communal, convivial spaces in marginalized urban communities, especially in Brazil.

website: https://samvalentine.land/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/realsamvalentine/

O Estrangeiro No Meu Celular

Conducting Remote Research in a Community of Self-Construction

Photograph by Participant #3, resident of Chapada do Rio Vermelho. The image, taken from atop the resident’s home, is intended to portray the “entire neighborhood” as an environment where the participant feels respected.

“I took this photo from the rooftop of the small three-story building where I live. I wanted to take an overview of the entire neighborhood,” a resident explains to me via WhatsApp, “because I feel respected in all the places I pass… someone always knows me.” The community pictured is Chapada do Rio Vermelho, an urban neighborhood of more than 20,000 residents in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil. Serving as the colonial capital of Brazil for more than 200 years, Salvador is today one of Latin America’s oldest and most picturesque cities.

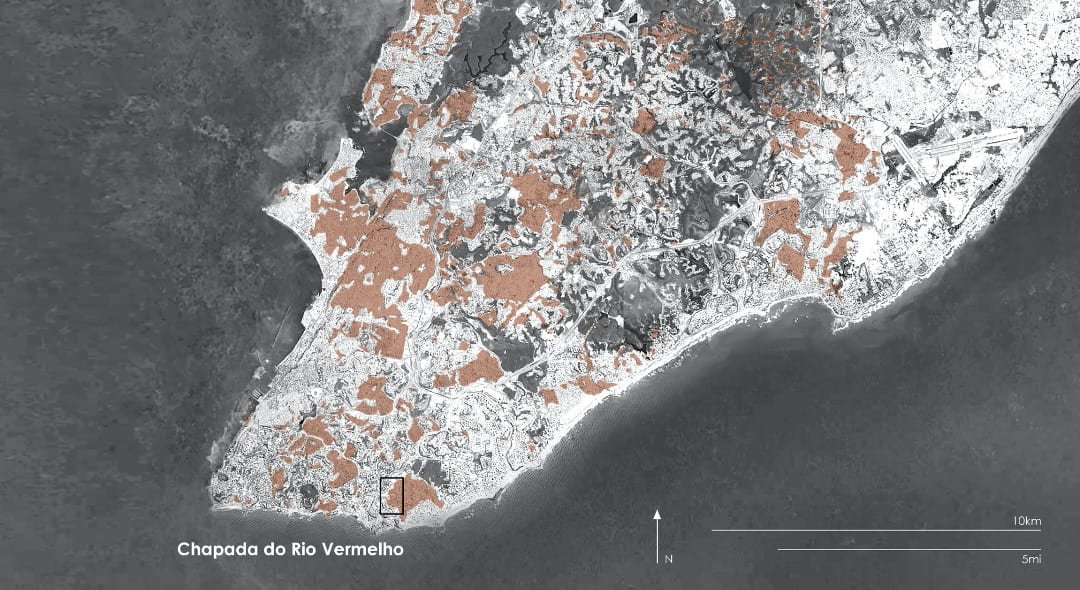

Composite map of Salvador da Bahia with community of Chapada do Rio Vermelho indicated. Areas of “informal habitation” are shaded in brown. Source: Angela Gordilho Souza, Limites do Habitar, 2008, p.455.

More than one-third of soteropolitanos (residents of Salvador) live in urban conditions labeled by some academics as “subnormal” and “informal.” When I submitted my proposal to the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies (DRCLAS) for the Summer Research Travel Grant in February 2020, I pitched a carefully sequenced trip that would fly me to Salvador, take me to the city’s main cultural attractions, and then allow me to immerse for months in these neighborhoods through “walking, listening, sketching, eating, photographing and casual conversations.” This exposure would be invaluable as I would soon begin work on my landscape architectural design thesis, taking place in one of these self-constructed neighborhoods of Salvador da Bahia.

By the time the good news of my grant came from DRCLAS, it was clear I would have to adapt my research plans to the realities of the Covid-19 pandemic. Realizing that most Brazilian adults have smartphones and that an astounding 98% of Brazilian smartphone users make use of the text-photo-audio-and-video application WhatsApp, I built a new methodology. I was inspired in part by an “auto-photography” project in Mexico, but rather than distributing cameras to community residents, I would use the phones already in their hands.

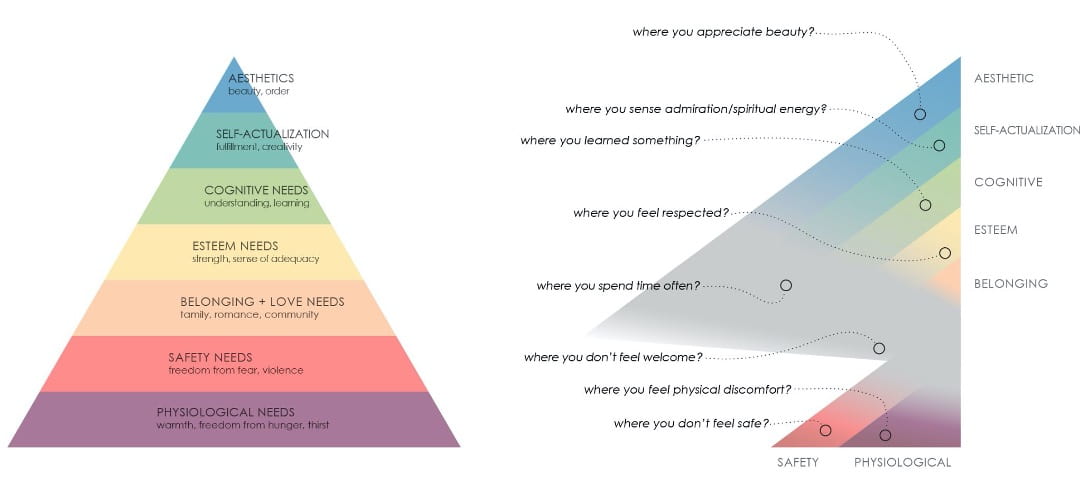

It was incredibly important to me to gain an understanding of a self-constructed community that minimized my inherent outsider bias, and I thus had to conscientiously design my auto-photography prompts. From mainstream news, cinema, and even academic literature there is an image of “the Brazilian favela” as a place of discomfort, dire need, and violence. Looking to psychologist Abraham Maslow’s “hierarchy of human needs” model, I recognized that these perspectives are weighted down to the bottom of the pyramid. I wrote eight questions, ranging in topic from higher-order needs like beauty and community ties, to, well yes, physical discomfort.

Hierarchy of human needs. Left: Interpretation of “A Theory of Human Motivation,” by Abraham Maslow, 1943. Right: My expansion of Maslow’s diagram to include quality-neutral areas (gray) of urban environments and to position my eight photo prompts within the hierarchy.

Writing a multi-phase script in English that I would later translate to Brazilian Portuguese, I included eight photo prompts and follow-up questions. Trying to head off unusable images, I also included four “rules” to participants: all photographs must be taken in outdoor spaces; they must be familiar places from residents’ daily lives; the participant must provide a mappable location for the image; and, finally, no selfies. As this research project is built around conversations with human beings, I submitted my proposed script and documentation to Harvard’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), which conducts a rigorous review of the ethics and potential harm a research project may pose to human subjects.

Following IRB review came the most influential step of my project. Key to both this research and my ensuing design thesis, I sought a “community partner”—an individual or institution embedded in a self-constructed community in Salvador. Someone who walks the streets daily, hears the needs of the community, and helps to build upon its strengths. Scanning a registry of Covid relief groups, I found Instituto Entre Aspas, Chapada Arte Cidadão, and their energetic leader, Gil de Leon. Through remote conversations with him, I was able to learn about the challenges facing the community of Chapada do Rio Vermelho, as well as the extensive arts-education programming that he is pioneering there. Through Gil de Leon, I was able to connect with eleven hand-picked residents; he shared my WhatsApp information with them, and the research began. Not only was his collaboration needed for me to contact residents, but he lent credibility to my research, encouraging residents of Chapada do Rio Vermelho to trust me.

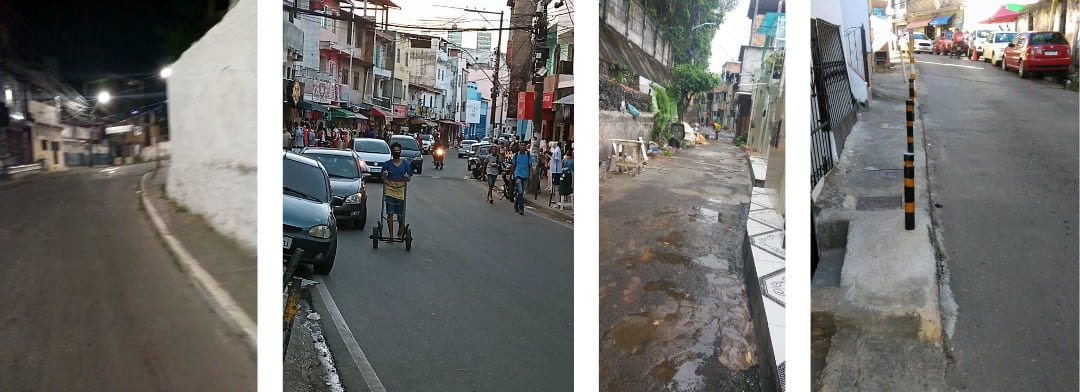

Constrained, car-crowded, and non-existent sidewalks were a common expressed concern of residents of Chapada do Rio Vermelho. Photographs by Participants #5, 3, 7, and 6.

The prompts that I employed yielded valuable auto-photographs illustrating the material conditions and spatial environment of Chapada do Rio Vermelho. The neighborhood is perceived by these residents as a crowded place where pedestrians and vehicles come into regular conflict. While these are not lofty, poetic topics, they are the nuts-and-bolts work of an urban landscape architect. I was able to see examples of what is working and what is not in the limited veins of open space that run through the neighborhood.

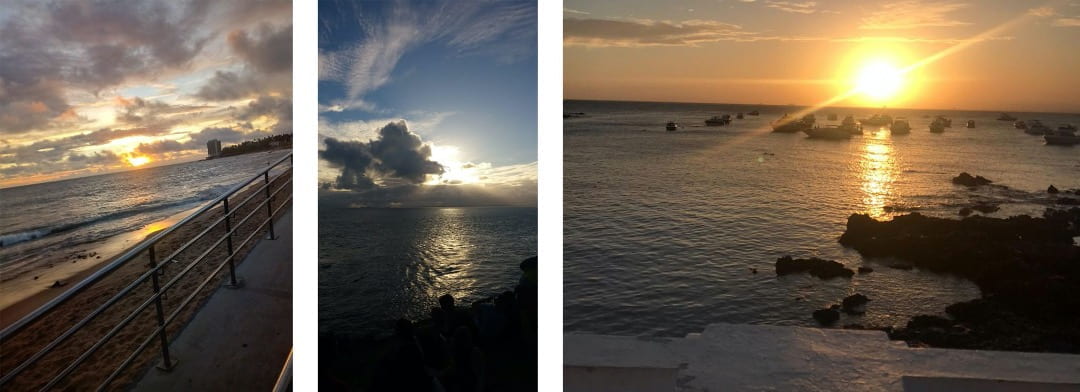

When prompted to “take a picture of an outdoor space that you think is beautiful, or like to spend time admiring beauty,” many residents sent images they took of beachfront sunsets. Photographs by Participants #2, 7, and 1.

While questions about “discomfort” resulted in photographs of divergent urban conditions, responses to my higher-order prompts for places of “beauty” were surprisingly aligned. Nearly half of the research participants messaged me images of sunsets over the beaches that wrap the city, especially the community’s nearest beach, Praia de Amaralina.

Another surprise came with my prompt: “where do you sense spiritual energy?” Designed to find places where one of Maslow’s highest-order human needs, “Self-Actualization,” is met, I understandably received many images of the façades of churches. Two residents, though, sent me photographs of sunsets as places where they sense spiritual force. Most compelling though, was the participant who insisted on sending two images, not one.

Both of these photographs capture places possessing spiritual energy to a resident of Chapada do Rio Vermelho, Participant #8.

The resident photographs and the subsequent conversations around them presented information about life in Chapada do Rio Vermelho that GIS and Google Maps Street View could not have shown me. Relationships between residents and social and political institutions are immaterial, sometimes invisible, and could have been missed even by a visiting researcher. I learned of soccer academies started 17 years ago to provide positive experiences for troubled youth. I was told of an oppressive environment of crime that has emerged in recent years on one resident’s home street. Sending an image of a police car when I prompted for a space that feels “unsafe,” another participant confessed to me that they “have a fear of catching a stray bullet… every time I see a police car.”

At time of this writing, I have weeks to wrap up my thesis. My design proposals are built on a foundation of 90 informative auto-photographs and the voices of a range of residents. I am weaving powerful threads of dance, graffiti, Afro-diasporic artistic expression, desire for nature contact, and police brutality and reconciliation into ideas for new community landscapes. Despite its remote nature, capturing the neighborhood of Chapada do Rio Vermelho through the eyes of its residents has proven invaluable to my understanding of the community. Hearing about the beauty and heartbreak in the direct words of its residents has shaped my design work.

More Student Views

Beyond Presence: Building Kichwa Community at Harvard

I recently had the pleasure of reuniting with Américo Mendoza-Mori, current assistant professor at St Olaf’s College, at my current institution and alma mater, the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Professor Mendoza-Mori, who was invited to Madison by the university’s Latin American, Caribbean, and Iberian Studies Program, shared how Indigenous languages and knowledges can reshape the ways universities teach, research and engage with communities, both local and abroad.

Of Salamanders and Spirits

I probably could’ve chosen a better day to visit the CIIDIR-IPN for the first time. It was the last week of September and the city had come to a full stop. Citizens barricaded the streets with tarps and plastic chairs, and protest banners covered the walls of the Edificio de Gobierno del Estado de Oaxaca, all demanding fair wages for the state’s educators. It was my first (but certainly not my last) encounter with the fierce political activism that Oaxaca is known for.

Public Universities in Peru

Visits to two public universities in Peru over the last two summers helped deepen my understanding of the system and explore some ideas for my own research. The first summer, I began visiting the National University of San Marcos (UNMSM) to learn about historical admissions processes and search for lists of applicants and admitted students. I wanted to identify those students and follow their educational, professional and political trajectories at one of the country’s most important universities. In the summer of 2025, I once again visited UNMSM in Lima and traveled to Cusco to visit the National University of San Antonio Abad del Cusco (UNSAAC). This time, I conducted interviews with professors and student representatives to learn about their experiences and perspectives on higher-education policies such as faculty salary reforms and the processes for the hiring and promotion of professors.