Transition to Democracy

The Lingering Debts

During the1970s and 80s dictatorships throughout much of Latin-America, thousands were illegally incarcerated, tortured, summarily executed, disappeared or forced into exile. Young people, intellectuals, professionals, students, workers were swallowed by the repressive machinery or left their countries without a trace for more secure destinations. Today, those with no alternatives choose the path into economic exile, leaving a vacuum that is difficult to fill. Among these economic migrants are very often those with something to sell, whether labor or intellect, those most recently trained in the under-funded national universities or simply the most desperate. In my country—Uruguay—during the 12-year dictatorship, nearly every family had a relative jailed or in exile for political reasons. Today nearly every family suffers the loss of a relative who has left the country in search of employment or better opportunities.

Although the dictatorships ended, the military in many countries retained sufficient influence to stifle efforts to review past human rights abuses by exerting pressure on political elites. To ensure democratic transitions, new civilian governments enacted or tolerated amnesty legislation or decreed pardons guaranteeing that crimes attributed to the security forces would not be prosecuted or punished. Thus, impunity is the price that the people of various Latin American countries have been paying ever since the 1980s. It has been the price for the transition to democracy, the recovery of their freedoms, and the promise of development and economic justice. As happens in all flawed transactions, 20 years later these societies have found the benefits have proven largely illusory. Large sectors of the societies that celebrated the return of elected civilian governments are today poorer, deprived of access to good schools or adequate health care, and generally disillusioned with the democratic system.

Most of the governments that took the reins of public administration after the dictatorships are doubly in debt. They owe a debt of truth and justice to the victims of military repression. They also owe a debt to their societies for failing to harness the creative energy that attended the return of democracy and improve social welfare. Both debts must be paid. The latter is most urgent as it deals with the very subsistence of entire families mired in the tragedy of poverty and unemployment. The former is equally essential as it bears on basic principles of democracy including equality before the law, separation of powers, and the independence of the judiciary. This lingering debt breeds injustice and corruption that in turn foster continued unemployment and poverty.

Electoral returns are beginning to castigate those politicians who merely frustrated people’s hopes and expectations, but it remains for the courts to punish those for whom corruption became a form of government. Meanwhile, the long and arduous quest for truth and justice continues. It is possible that this debt can never be repaid: what is the truth and how many interpretations exist? What form of justice would satisfy victims who for decades have endured the added insult of official denial and neglect? And what would constitute satisfactory reparation for society as a whole, which has tolerated a perversion of the principle of equality before the law—and of democracy for that matter—and the existence of a judicial system that is precluded from reaching particular sectors of society?

IMPUNITY CHALLENGED

In presenting his human rights proposals this August, Chilean President Ricardo Lagos said, “The abrupt transitions, the impunity, the denial of truth and justice ultimately deteriorate and, as in the case of a poorly healed wound, recur in social life, generating more pain and even larger institutional complications.” Nothing could be more evident. Nevertheless, recognition of this truth and the ways in which this “poorly healed wound” is confronted vary radically across countries that not long ago were united in their repressive approaches to governing.

The countries of the southern cone illustrate the diversity of response. The Argentine Congress recently declared the nullification of the Full Stop and Due Obedience laws and in Chile the executive presented a series of proposals to address “pending issues in the field of human rights.” Uruguayan efforts to “seal the peace” led to the establishment of a “Peace Commission” and yet politicians persist in their defense of amnesty and impunity as the price of the democratic transition.

The election of President Nestor Kirchner in Argentina brought winds of change. When the Senate overturned the amnesty laws on August 2, 2003, the doors opened to the prosecution of thousands of cases of forced disappearance, torture, and extra-judicial execution committed during the period of military rule. Although this has been perhaps the most extraordinary recent development, one cannot underestimate the significance of additional measures such as the call for the resignation of a number of high-ranking military officers and Supreme Court justices and the ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutes of Limitation for War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity.

On August 12, 2003, the Chilean government announced its intention to “persevere in the delicate process of healing the wounds produced by the serious human rights violations” committed during the government of General Pinochet. Although President Lagos did not take the decisive step of annulling the amnesty decreed by the military regime in 1978, he did state his conviction that the courts of law “constitute the forum in which to seek truth and apply justice.” He simultaneously announced a series of measures intended to: expose the full truth; ensure the independence and efficiency of the judiciary; review and improve reparations schemes; and improve the protection, promotion and respect for human rights. Several of the proposed measures are controversial. Perpetrators who had been following orders or who present themselves voluntarily to the courts and provide relevant information regarding human rights abuses stand to benefit from reduced sentences or full pardons. In general, however, these measures demonstrate the government’s determination to overcome impunity.

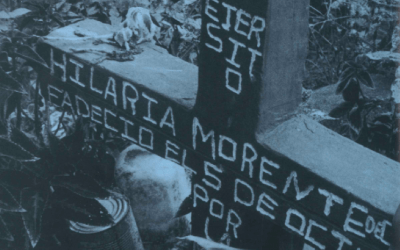

In August 2000, Uruguayan President Jorge Batlle created the Peace Commission to “determine the situation of the detained-disappeared during the military regime,” to fulfill an “ethical obligation of the state” and to forever “seal the peace among Uruguayans.” The final April 2003 report contains information confirming at least 31 of the 38 complaints of detention-disappearance in Uruguay, as well as a significant number of the approximately 200 complaints of Uruguayan citizens disappeared in Argentina and other neighboring countries. The report is the first official recognition of responsibility for the commission of crimes against humanity, yet it clearly falls short of ending the debate on the legacy of the dictatorship. First, the Commission’s mandate did not extend beyond the cases of the detained-disappeared to include the far more numerous cases of torture and prolonged detention that so characterized the Uruguayan military regime. Second, the Commission’s weak mandate and lack of collaboration from the armed forces precluded the Commission from fully clarifying the circumstances surrounding cases of detention and disappearance. Third, the Commission’s report stops short of recommending formal justice for the victims’ families. And finally, the Commission’s procedures failed to engage the perpetrators themselves. In sum, this initiative has done little to foster reconciliation or, as the president hoped, “pacification” among Uruguayans.

Other Latin American countries are confronting past crimes with varying degrees of success. In Peru for example, after the fall of the dictatorship of Fujimori and Montesinos, progress was made in several human rights cases. A Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established and, after two years of work, produced its final report. The report, presented in August 2003, describes more than 60,000 deaths attributed to insurgent groups and the various governments that confronted them, and recommended the implementation of an “Integral Reparations Program” and “the effective exercise of justice.” Consequently, a certain number of cases were transferred to the Attorney General’s office for prosecution.

The situation in El Salvador and Guatemala is less encouraging. In the former, justice remains elusive ten years after the signing of the peace accords. Last August, for example, the UN Human Rights Committee expressed regret that the 1993 General Amnesty Law continues to impede the investigation and punishment of those responsible for the commission of serious crimes during the armed conflict, including those substantiated by the Salvadoran Truth Commission. In Guatemala, after nearly a decade of UN verification of an elaborate set of peace accords, impunity still prevails. Worse yet, General Efraín Rios Montt, responsible for the most serious violations committed during the armed conflict, might—with the complicity of a weak judicial system—have yet another chance to preside over the future of this battered country.

INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE AMNESTIES

The struggle to annul the amnesties in various Latin American countries began almost as soon as they were adopted. The UN Human Rights Committee and the Interamerican Commission of Human Rights quickly declared that governmental efforts to impede the investigation and sanctioning of the terrible rights violations committed during dictatorships or internal armed conflicts constituted violations of relevant international obligations. The most recent and transcendent episode in this struggle in our hemisphere was the decision of the Interamerican Court of Human Rights on the illegality of amnesty legislation.

In early 2001, the Court, an independent organ of the Inter-American human rights system, considered the Barrios Altos case in which the government of Peru was accused of the commission of extrajudicial executions and of invoking an amnesty law twice to protect the individual perpetrators from trial. In November 1991, six heavily armed men had broken into a building in the Barrios Altos neighborhood of Lima, forced the people present to lie down on the floor and shot them. Fifteen people were killed and four gravely wounded. The ensuing investigation revealed that the attackers were members of the Peruvian army’s “death squad” called “Grupo Colina.” A serious judicial investigation was not conducted until 1995. However, just as the courts began to summon suspects who were members of the military to testify, the Peruvian Congress passed an amnesty law (Law No. 26.479), which exonerated the military, police and civilians of human rights violations committed between 1980 and 1995. When the legality of this law was challenged and the judges tried to continue with the proceedings, Congress adopted a second amnesty law (Law No. 26,492), broadening the reach of the previous amnesty law and declaring that the amnesty was beyond the scope of judicial review.

In its decision on the merits, the Inter-American Court reiterated the rationale found in pronouncements of other international bodies on the issue of amnesty laws and endowed them with judicial authority. Thus, the Tribunal established that “all amnesty provisions, provisions on prescription and the establishment of measures designed to eliminate responsibility are inadmissible because they are intended to prevent the investigation and punishment of serious human rights violations such as torture, extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary execution and forced disappearance, all of them prohibited because they violate non-derogable rights recognized by international human rights law.” Amnesty laws prevent the victims’ next of kin and the surviving victims from being heard by a judge, violate the right to judicial protection, prevent the investigation, capture, prosecution and conviction of those responsible for the violations, and obstruct the clarification of the facts. As a consequence, amnesty laws that “lead to the defenselessness of victims and perpetuate impunity” are manifestly incompatible with the aims and spirit of the American Convention on Human Rights, lack legal effect and may not continue to obstruct the investigation of the grounds or the identification and punishment of those responsible.

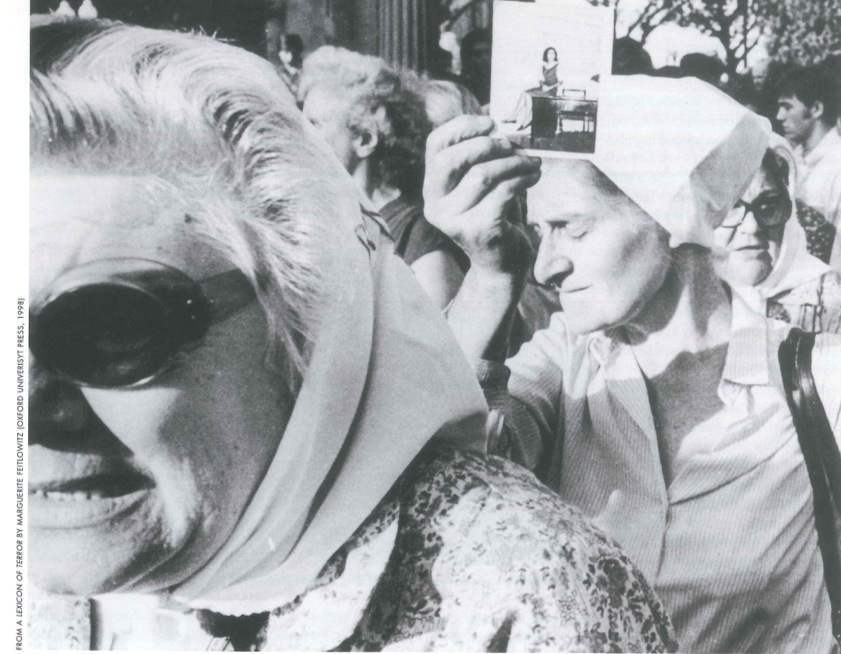

Relatives of the disappeared protest in Argentina.

Judge Sergio García-Ramírez, in his concurring opinion, affirmed: “I am very much aware of the advisability of encouraging civil harmony through amnesty laws that contribute to re-establishing peace and opening new constructive stages in the life of a nation. However, I stress—as does a growing sector of doctrine and also the Inter-American Court—that such forgive-and-forget provisions ‘cannot be permitted to cover up the most severe human rights violations, violations that constitute an utter disregard for the dignity of the human being and are repugnant to the conscience of humanity.”

LAW AND REALITY

Reality has not yet caught up with the dictates of the law. Victims or their relatives continue to confront measures that preclude justice and governments vary between those that are open to ending impunity and those that dogmatically maintain that impunity is essential to the preservation of democracy. Meanwhile society has suffered a series of indignities, including blackmail by the military, limitations on the independence of the judiciary and the unequal treatment of citizens. As if to add insult to injury, the recent economic crises have forced the realization that absent honest leadership and wise economic management transition to democracy alone does not guarantee widespread economic and social well-being.

The debt of truth and justice must be repaid without further delay. Impunity might be addressed differently in each society, but I would suggest three guiding principles that ought to govern any country’s approach. First, international law makes the nullification of amnesty laws and pardon decrees an imperative for all governments. Latin American countries cannot continue praising themselves internationally for their political systems and simultaneously flout their international human rights obligations. Second, whether impunity legislation is formally overturned by the Executive or Legislative branches or not, judicial systems must be granted full independence to adjudicate human rights claims. A government that calls itself democratic cannot attack or criticize the judicial system for adjudicating past crimes. Finally, our democracies should rethink the role of the armed forces. If it is true that impunity was a response to pressure by the same military institutions that altered constitutional orders and imposed dictatorships, then their existence as a pressure group must be revisited. Why should the people of Latin-America maintain armies, even with reduced budgets under democratic governments? At the end of the day, in my country, Uruguay, the armed forces that did away with the constitutional system was much smaller than during the dictatorship it established.

Latin-American democracies must begin to deliver on their promises.

Fall 2003, Volume III, Number 1

Renzo Pomi, Harvard Law School LLM ’98, is an Uruguayan lawyer who currently represents Amnesty International at the United Nations. The views expressed in this article are solely attributable to the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Amnesty International.

Related Articles

Human Rights: Editor’s Letter

During the day, I edit story after story on human rights for the Fall issue of ReVista. During the evening, I work on my biography of Irma Flaquer, a courageous Guatemalan journalist who was…

ONGs en América Latina y los derechos humanos

Las ONG ofrecen mil modos de recordar la dignidad humana a los gobiernos y las sociedades. Las dos experiencias que esbozo en esta nota reflejan algunas de las estrategias asumidas por…

Peru’s Human Rights Coordinating Committee

The human rights abuses that devastated Peru from the early 1980s to the mid 1990s are once again an issue of debate in that country with the release of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation’s…