Peru’s Human Rights Coordinating Committee

Promoting Human Rights in Changing Circumstances

Photograph by Joyce Penfield.

The human rights abuses that devastated Peru from the early 1980s to the mid 1990s are once again an issue of debate in that country with the release of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation’s final report. The Commission was created on June 4, 2001, by interim President Valentín Paniagua and subsequently ratified by President Alejandro Toledo. Composed of twelve members and one observer, its mandate included investigating human rights abuses by both government and insurgent forces, presenting proposals for reparations and human rights-related reforms, and establishing mechanisms for follow-up. One very important objective of the process underway is to promote reconciliation with the victims of political violence.

The report, presented on August 28, 2003, concludes that more than 69,000 people were killed in acts of political violence in Peru between 1980 and 2000, a figure that far exceeds the previously accepted total of 30,000 deaths. More than half of these killings were perpetrated by the Shining Path. Additionally, the report finds that three out of every four deaths were Quechua-speaking rural peasants. The commissioners strongly critique the political actors who either allowed or ignored the human rights violations committed by state security forces against the most vulnerable and marginalized sector of Peruvian society.

The Peruvian human rights community described below played an integral role in building popular and political support for the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The former Executive Secretary of Peru’sCoordinadora Nacional de Derechos Humanos, Sofia Macher, was a member of the Commission and scores of human rights lawyers and activists were incorporated into its staff. Peruvian human rights groups provided support to the Commission throughout the course of its investigation and are now engaged in advocacy campaigns to promote the implementation of the report’s recommendations.

The Coordinadora Nacional de Derechos Humanos (National Human Rights Coordinating Committee) is an umbrella organization with more than 60 human rights organizations from across Peru. Since its 1985 founding, the Coordinadora has earned a reputation as one of the most effective country-based human rights movements in Latin America. Over the years, the Coordinadora has managed to function effectively as a coalition even as the situation in Peru dramatically changed.

The Coordinadora and its member organizations operated for years in a violent and polarized situation between the Shining Path insurgent group and Peruvian government security forces. Being caught in the crossfire gave greater impetus to the need for unity among Peruvian human rights groups. This time of extreme political violence was followed by a prolonged period in the mid-1990s of authoritarian rule under President Fujimori. In this new context, the Coordinadora shifted from a more traditional agenda focused on political and civil rights to join broader citizen efforts to restore democratic rule in Peru during a time of regime change and transition.

Like other human rights groups in similar circumstances, the coalition faced four fundamental questions:

- How to maintain and sustain a coalition in situations where circumstances change dramatically?

- How to build unity between diverse groups within a coalition while at the same time ensuring input and participation by those members that are traditionally more marginalized?

- To what extent should human rights promoters seek out opportunities for constructive engagement with the State?

- When and how to build alliances with other sectors of civil society and with the international community?

THE PROLIFERATION OF POLITICAL VIOLENCE

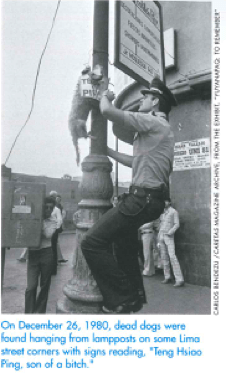

May 18, 1980 marked a turning point in Peru’s history. Elections were held after 12 years of military rule, and the Shining Path—the most ruthless insurgency to emerge in Latin America—launched its armed revolution against the Peruvian state in the highlands. Shining Path cadres burned ballot boxes in the small village of Chuschi, in the province of Ayacucho. Residents in Lima awoke to find dead dogs hanging from lampposts and traffic lights.

The Peruvian government’s subsequent counterinsurgency tactics mimicked the violent methods employed in Argentina and Chile: reports began circulating of extrajudicial executions, disappearances, massacres and torture at the hands of state security forces. A vicious spiral of violence ensued.

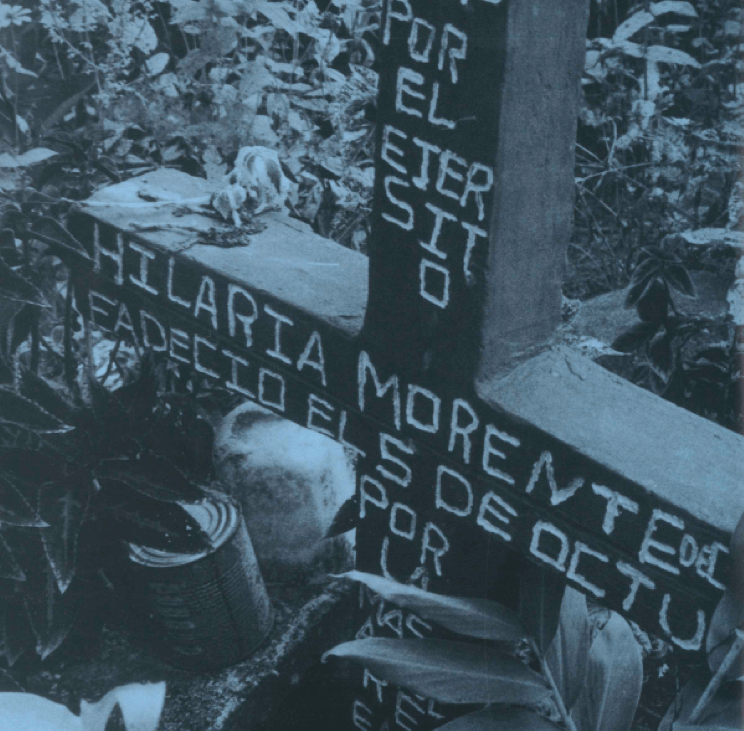

In the years that followed, Peruvian citizens, particularly peasants, were caught between the armed forces’ brutal counterinsurgency campaign and the Shining Path’s terrorist acts. Small human rights groups, often called Human Rights Committees (CODEHs) were formed around the country to aid the victims of violence. They brought together government officials, religious leaders, teachers, lawyers, social workers, psychologists, leaders of unions and grassroots organizations, and sometimes political party representatives. Most CODEHs combined legal defense and human rights education, utilizing local media outlets to address human rights issues concerning the local population, often with the local Catholic Church’s support. In the emergency zones, victims’ family members (familiares) formed organizations. Most familiares had loved ones who had disappeared; they were overwhelmingly poor, Quechua-speaking peasants from isolated rural areas—Peruvian society’s most marginalized sector. The familiares organizations offered both solidarity and possibilities for joining with others to take action. Perhaps most importantly, as one woman stated, “There, we were told where bodies had been found and with that information, we would go out and look for the cadavers, in search of our loved ones.”

CAUGHT IN THE CROSSFIRE

Like much of Peru’s peasant population, human rights activists increasingly found themselves caught in the crossfire between the military and the insurgents. Conservative political leaders often viewed human rights as an obstacle to waging a successful war against the guerrillas.

The Peruvian military and police routinely targeted human rights activists, mistakenly linking them to the Shining Path. As in other Latin American countries, state agents were responsible for most of the attacks on the human rights community. However, in contrast to the situation elsewhere, the Peruvian human rights groups were also brutally attacked by the guerrillas. Shining Path routinely sent death threats to local human rights groups and attempted to infiltrate their activities as a form of intimidation or with the intention of eventually controlling them. Shining Path “liquidation squads” killed scores of popular leaders every year.

THE FORMATION OF THE COORDINADORA

By 1984, momentum grew for the creation of a unified human rights movement in Peru. Key human rights leaders, particularly those from the provinces, recognized that unity could help open up political space, increase their effectiveness, enhance their credibility and perhaps offer some protection against the threat of both the military and the Shining Path.

In January 1985, 107 people representing more than 50 human rights organizations attended a national meeting (Encuentro). After much heated discussion, the meeting’s final declaration denounced human rights atrocities committed by the security forces and the insurgents.

The Coordinadora Nacional de Derechos Humanos in Peru was formed at the Encuentro with the purpose “to coordinate and support the work in defense of human rights undertaken by organizations at the national level.” (Reglamento de la Coordinadora Nacional de Derechos Humanos, May 20 1985).

IMPACT OF EXTREME POLITICAL VIOLENCE ON THE COORDINADORA

Extreme political violence was a day-to-day reality for the Coordinadora and its members. Fear permeated the human rights movement across Peru. Those in areas hardest hit by the violence operated at great personal risk.

In the face of extreme violence by both sides, the space to carry out human rights work narrowed and closed altogether in some areas. Provincial groups, particularly organizations of familiares, felt marginalized and out-of-touch with activities in the capital, yet had to rely more and more on Lima-based organizations for assistance. Constant security threats and a climate of suspicion prevailed.

CONSTRUCTIVE ENGAGEMENT?

Given the high levels of political violence during the Coordinadora’s early years, the extent to which human rights groups should seek opportunities for constructive engagement with the State was another hot debate. The civilian government had largely abdicated its responsibility for dealing with the insurgents to the military, then responsible for the bulk of human rights violations. The Comando Rodrigo Franco (CRF) death squad allegedly operated out of the Ministry of the Interior. With the exception of a handful of outspoken deputies, the Peruvian Congress gave unbridled support to the military’s counterinsurgency strategy.

In these circumstances, Coordinadora discussions wrestled with the pros and cons of attempting to work with state actors to address the human rights crisis. Some viewed the State as the “enemy”; others argued that some state actors were potential allies. Each group within the Coordinadora adopted its own approach in dealing with the State. Many did interact with government officials at the local, regional and national levels. Some groups focused on denunciation and protest while others sought constructive engagement to push legislative reforms. Still others took the position that “one must confront, but also influence,” combining the two strategies.

REGIME CHANGE AND TRANSITION

In the 1990 presidential elections—with the country in economic and political ruin—an unknown political outsider who donned a traditional Andean poncho and campaigned from a tractor, came out of nowhere to win. Despite his portrayal as a populist, Alberto Fujimori implemented his opponent’s sweeping neo-liberal economic reform and—with the assistance of his secretive and nefarious advisor, Vladimiro Montesinos—developed a tight relationship with the country’s revamped intelligence services and the military.

In April 1992, Fujimori suspended the constitution, dissolved congress and temporarily closed the judiciary. Although the autogolpe, or self-coup, marked the beginning of eight years of authoritarian rule, most Peruvians viewed this iron fist approach as necessary to confront Shining Path’s terrorist violence.

Peruvian history took yet another dramatic turn in September 1992, when Abimael Guzmán, the messianic Shining Path leader, was captured and his unshaven, forlorn image broadcast across the nation. This prompted a precipitous drop in violent acts committed by the Shining Path and, ultimately, its near demise. As a result, state-sponsored human rights violations declined proportionally, and human rights groups found themselves challenged by a new crisis of democratic governance and the rule of law.

The Coordinadora adapted its work to the changing scenario, analyzing the obstacles and opportunities the new circumstances presented for the movement. Relations with the national government were increasingly antagonistic and the regime’s authoritarian nature meant human rights guarantees remained more distant than ever. However, the end of the crisis of political violence made it harder for the government to justify its strong-arm tactics. On issues that did not threaten Fujimori’s pillars of power—the military and the intelligence services—he was sensitive to public opinion and there were limited opportunities for reform.

The Coordinadora’s “In the Name of the Innocent” campaign exemplifies how the human rights community quickly adapted and carried out effective advocacy within Fujimori’s repressive regime. Shortly after the autogolpe, Fujimori issued decrees creating military courts to try those accused of “treason”—defined as a form of aggravated terrorism—and “faceless” civilian courts (the identities of the judges were kept secret) to try accused terrorists. The draconian legislation all but eliminated due process guarantees and the right to an adequate legal defense. The number of people detained on terrorism charges skyrocketed.

The Coordinadora launched an extensive media campaign to release innocent Peruvians jailed as terrorists.. By 1995, 87% of Peruvians polled in Lima said they thought there were innocent people in jail on terrorism charges (A la Intemperie: Percepciones sobre derechos humanos. Lima, Peru: Coordinadora Nacional de Derechos Humanos, 1996). Politically astute, Fujimori noted the shift in public opinion and began a pardon process.

The role of human rights was still evolving. At the 1995 Encuentro, a major discussion took place about what role the Coordinadora should have in promoting economic, social and cultural rights (ESCR), and what priority they should be given in the coalition’s work plan.

Coalition members also wrestled with how to respond to the crisis of democratic rule, agreeing that human rights guarantees could not be institutionalized before Peru returned to a more democratic path. At the 1997 Encuentro, the Coordinadora membership officially adopted a pro-democracy platform calling for strengthening democratic institutions and the rule of law, a logical next step in the coalition’s evolution. The Coordinadora allied itself with social movements and other pro-democracy civil society organizations.

The Coordinadora’s increased focus on democracy impacted the way it thought about and carried out its work. The 1997-1999 work plan adopted at the Encuentro incorporated the area of “democracy and human rights” to promote more active citizen participation in government. Much of this work was cast in terms of the reconstruction of the country’s social fabric, creating spaces for civil society groups to come together and encouraging civic education. Then-Executive Secretary Sofía Macher noted a fundamental shift in “the central focus of our work from individual cases to the political system of the country and how it affects human rights.” In the 2000 elections, the Coordinadora played a dramatic role.

Independent of political parties or movements, the Coordinadora was seen as an honest broker, above the political fray, yet clearly committed to the democratic struggle. Moreover, the Coordinadora’s cooperative nature set it apart. While the Executive Secretary had a high profile public figure, the Coordinadora was not seen as imposing its point of view or trying to co-opt other civil society organizations. With a reputation for principled positions, its opinion was valued by domestic and international actors gauging the validity or fairness of government actions with regards to the electoral process.

In contrast to its strategy in past elections, in 2000 the Coordinadora positioned itself in the eye of the electoral storm, questioning whether Fujimori would allow any other candidate to run, and potentially win, the elections. The Coordinadora, like many other civil society actors, came down firmly on the side of free and fair elections and against manipulations by the incumbent. Coordinadora member organizations helped document and denounce the electoral shenanigans taking place and shape national and international public opinion through a media campaign and the dissemination of information and analysis abroad.

The Asociación Civil Transparencia, an independent electoral watchdog group, was the primary organization reporting on the electoral process and mobilizing thousands of Peruvian citizens as election observers. The Coordinadora assisted in these efforts first by convening a broad cross-section of civil society, pulling together churches, universities, unions and other non-governmental organizations to support independent monitors’ efforts. Second, provincial Coordinadora member organizations became an important source of election monitors at local polling stations—essential work during the first round of voting in April 2000—and eventually the Fujimori government was forced to concede a run-off. The withdrawal of both national and international monitors for the second round meant that Fujimori entered his third term in office lacking domestic and international legitimacy.

After the election, the head of the Organization of American States (OAS) electoral monitoring mission in Peru, Eduardo Stein, applauded: “The work undertaken by the organizations that promote human rights in Peru, under the effective leadership of the Coordinadora” as being “one of the principal protagonists in the democratic transition that is, happily, under way in Peru today.” (Letter by Eduardo Stein to Sofia Macher, July 4, 2001.)

CHALLENGES FOR THE COORDINADORA POST-FUJIMORI

On September 16, 2000, President Fujimori announced he would hold new elections in which he would not run and that he would dismantle the feared intelligence service. Both Montesinos and Fujimori fled the country; Montesinos was extradited to Peru to face prosecution for dozens of crimes, while Fujimori remains in exile in Japan. The period of authoritarian rule ended abruptly and Peru entered yet another transition period, this time toward democratic rule.

Once again the Coordinadora faced the prospect of adapting to a changing political landscape ripe with new opportunities and challenges. Political space had finally opened to reform and the formulation and debate of concrete policy proposals. At the same time, the Coordinadora may find itself in the uncomfortable position of confronting former colleagues with long trajectories in the human rights movement now assuming government posts. How will the Coordinadora develop strategies for constructive engagement to influence reform processes while maintaining its independence vis-à-vis the State? The Coordinadora’s challenge is to “identify and adequately locate the space for the human rights movement in a democracy,” as former Executive Secretary Sofia Macher so eloquently stated. The Coordinadora and its members will grapple with this challenge in the coming years.

Fall 2003, Volume III, Number 1

Coletta A. Youngers is a consultant for the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA). This article is based on a Case Study Prepared for the Hauser Center for Nonprofit Organizations/Program on Philanthropy, Civil Society and Social Change in the Americas (PASCA), Harvard University. Susan C. Peacock was also a consultant for the case study.

Related Articles

Human Rights: Editor’s Letter

During the day, I edit story after story on human rights for the Fall issue of ReVista. During the evening, I work on my biography of Irma Flaquer, a courageous Guatemalan journalist who was…

ONGs en América Latina y los derechos humanos

Las ONG ofrecen mil modos de recordar la dignidad humana a los gobiernos y las sociedades. Las dos experiencias que esbozo en esta nota reflejan algunas de las estrategias asumidas por…

Human Rights and Reconciliation

I feel the strongest of bonds with Cuba. I was born there and left as an 11-year old with my family for the United States shortly after the revolution came to power. We thought our stay here would…