A Brief Chronicle of Chilean Cinema

Culture and Beyond

As I see it, the development of Chilean cinema during the last years followed two general paths.

- The first line of development concerns the institutional framework. Cultural enterprises, especially film, have played a growing role in the democratization process.

- The second concerns the aesthetic, narrative, and thematic processes which cinema has developed as a cultural-artistic phenomenon.

In merging the two we may find the social and cultural roles which cinema has played in renewing forms, approaches and questions within an ongoing historical process. From here we can ask another question that has been raised lately about the development of diffusion and reception of the cinema as cultural-social phenomenon.

GHOSTS, RETURNS, UNCERTAINTY. THE CINEMA OF TRANSITION.

During 2004 Congress promulgated a law of audiovisual finance long awaited by those who intend to build a cinema industry.

Films that made an impact during the first decade of democracy (1988-1998), had to confront a double challenge: to foster an interest in building a cinema industry, attract audiences to the theaters (thus strengthening the viability of cinema), and, at the same time, to get involved in social and political issues from the end of dictatorship and the “democratic turn.” The filmsImagen Latente (Perelmann, 1988) and Cien niños esperando un tren (a documentary by Ignacio Agüero, 1988), opened a new period as they were the first ones to approach dictatorship issues. Imagen Latente, a dark film, takes place during the dictatorship; it tells the story of a photographer who tries to find traces of her “missing” brother. The second film, a subtle documentary, shows the work carried out by a teacher (Alicia Vega, an important investigator of cinema in our country) with a group of children in a cinema workshop. Less direct, but more socially focused than Perelmann’s film, Agüero’s documentary shares with it an emphasis on the social importance of an artistic device. In Perelmann’s case, it is the use of the camera, which shifts from being a fashion and advertising device to recording the truth by capturing the torture places. In the Agüero documentary filmmaking takes a more playful turn, but it also transforms social reality: in the middle of dictatorship cinema becomes a tool for pedagogy, a way to connect children who have been separated by the economic system. During the next years cinema will deepen both themes: the recent memories of dictatorship and the marginalization and inequality which seem to have been its legacy.

Three remarkable works dealing with the first theme are: La Frontera (Ricardo Larraín, 1991), Amnesia (Gonzalo Justininao, 1994) and La memoria obstinada (Patricio Guzmán, 1996). The first one, a co-production of Chile and Spain, won awards abroad (Silver Bear in Berlin, best script award in Havana), and was very well received locally. The film takes place in a desolate landscape in southern Chile, and tells the story of Ramiro Orellana, an ex-militant whom the dictatorship government sent to work there. With a brilliant gallery of characters (a Spanish man who fought in the Civil War, a lonely woman, a diver), this film creates remarkably deep images which link the destructive power of the landscape with the social reality of the country. Larraín creates a robust and poetic film, aspects of which we might now call “magical realism.” Amnesia and La memoria obstinada project different moods. The first one is a dark drama which tells a story of revenge against a torturer (painted in broad strokes verging on the grotesque). The second is a documentary by one of the Chilean directors who had a brilliant career outside of Chile and became famous with La Batalla de Chile (1975-1979), a documentary about the rise and fall of Allende’s government. In La memoria obstinada, Guzmán uses oral testimony told by several voices (linked by history, exile, family ties), to show the break with past utopias and the frustrations they leave behind, as well as the deep injuries left by the political and military violence of the recent past of Chile. With this film, widely discussed in left-wing political and cultural debate, Guzmán started a line of investigation and raised the possibility of reconciliation [June, not sure about this] that came to characterize later documentaries, which made deep inquiries, within the framework of the democratic process, into the social construction of memories.

The second path followed by the first wave of Chilean cinema sought to show, comment on or denounce certain deep changes brought by the political transition and which produced a curious “Realism” that also appeared in the 90s elsewhere in Latin America (Gaviria in Colombia, and the first new Argentine cinema). This type of “Realism” is defined in opposition to trends of the 70s, as it flirted with some conventional genres (from black genres to dramatic and spicy comedy) and sometimes with the rawness and violence of the social situation. The first example was Caluga o Menta (Justiniano, 1990), a powerful if crude portrait of the disadvantaged who were brought down by the neo-liberal economics and politics of the dictatorship. The film also notes the emergence of television as social phenomenon. Both themes are even more focused in Johnny 100 pesos(Graef Marino, 1994), a thriller that features a marginal school boy, member of a gang that assaults a videoclub, an assault that becomes a media and television event. The film of Graef Marino is a rare case in Chile: his narrative works like a clock in support of his open desire to do commercial cinema that still focuses on the social changes and uncertainty of the early 90s. By the year 2000, this political emphasis (criticism of the media, and plots centered on marginal situations) had lost its force and film moved into popular comedy, which in its best moments (El chacotero sentimental, Galaz, 1999; Historias de Fútbol, Wood, 1997; y Sexo con Amor, Quercia, 2004), not only broke box-office records but also created, at the institutional level, the appropriate climate for the promulgation of the cinema law I mentioned earlier.

RUINS AND REFLECTIONS

Aquí se construye (2000) by Ignacio Agüero and Machuca (2004) by Andrés Wood both started new movements in Chile’s cinema. The first film, a documentary (by the director of Cien niños esperando un tren), records the construction of new buildings – in bad taste– in the residential neighborhoods of Santiago de Chile. With a subtle blend of existential and geographic features (the documentary follows a university teacher who is the observer), Agüero builds an archaeology of places and emotions about the city. In the process of reconstruction of neo-Santiago (work of economic neoliberalism), he finds ghostly ruins and fragments that still inhabit the city. Machuca is a fictional story of a child that takes place during the rise and fall of Allende’s government. Projecting a great sense of empathy with the audience, the film satisfied the public’s emotional and personal expectations by showing the social landscapes and the emotional breaks during the period 1970-1973. The film not only served as a bridge to establish an open social dialogue about the events, but also established a “canon” of how to represent 1973, a position which is balanced at a middle point between complete rejection of ideology and full transparency.

After 2004, year of the law of cinema, everything suddenly changes.

- The Universidad de Valparaíso, Universidad de Chile and Universidad Católica offer careers in cinematography, which means the expansion and establishment of formal instruction in this field.

- The number of releases had reached a peak in 2003 with nearly 30 new shows; since the 90s their numbers have doubled and tripled.

- Work with digital cameras lowers the costs of production, which will lead to the production and even the screening of films in digital format.

- The rise of dozens of new film festivals that require diversification stimulates the industry to grow in quality and specialization, from independent cinema to documentary, from underground films to old films.

- The birth of a “cultural cinema field” brings out new web sites that specialize in film criticism (Fueradecampo.cl, Mabuse.cl, laFuga.cl) and the emergence of a publisher specializing in topics of cinema.

- In the last few years there has been an obvious decrease in the number of spectators who go to cinema (a transnational phenomenon), a problem that has led filmmakers to question the sacred custom of release on the big screen. The year 2008 has been called the year of the “audiences’ crisis” for Chilean cinema.

These, among others, are the factors that have contributed to the diversification of the cinematic milieu in recent years. Today’s formats, forms and modalities of cinematographic representation are less clearly defined: some documentary films have begun to open to fragmentation and reflection on their language (Ningún lugar en ninguna parte, 2004; Arcana, 2006, Dear Nonna, 2004); some films blur the border between documentary and fiction (El Pejesapo, Obreras saliendo de la fábrica, Alicia en el país, El astuto Mono Pinochet y la moneda de los cerdos, 2004), some display the proliferation of an ever more intimate, literary and confessional “I” (La ciudad de los fotógrafos, 2006; Calle Santa Fe, 2006; Retrato de Kusak, 2004) and, during the last years, some produce a re-visitation (topographic, fragmented and discursive) of Santiago (Tony Manero, 2008; Mami te amo, 2008; Tiempos Malos, 2009). All of them confirm that even though it is not possible to establish a clear direction, some of the themes brought out at the beginning of democracy will continue to deepen (collective and social memories) and others will have to mutate or to adapt to new digital technology. What is clear is that whatever happens, the cinema –the one we are interested in– will know how to adapt to its times, and it will be necessary then to reinforce the cultural fields of reception of these future films, which will tell us about ourselves in ways that we might not even be able to recognize.

Pequeña crónica del cine Chileno

Si tuviese que definir el recorrido del cine Chileno durante los últimos, tendría que establecer al menos dos líneas en los que es posible detectar sus recorridos.

- En primera instancia el marco institucional y el creciente rol que han adquirido las industrias culturales- y en especial, el cine- en el proceso de democratización.

- En segunda instancia, en los procedimientos estéticos, narrativos y temáticos que ha ido encontrando el cine como fenómeno artístico- cultural.

En una conjunción de ambas, podemos encontrar el rol social y cultural que ha tenido el cine renovando las formas, enfoques y preguntas en torno a un proceso histórico contingente. Es desde aquí que nos cabe señalar una última cuestión que ha ido configurándose durante los últimos años en torno al desarrollo de campos de difusión y recepción del cine como fenómeno socio-cultural.

Docente y crítico de cine, con estudios en Cine, Estética y Comunicación y cultura. Ha realizado clases de Estética del cine, Cine Latinoamericano y Cine documental. Actualmente centra sus actividades como gestor, editor y crítico en la página especializada <http://www.lafuga.cl>www.lafuga.cl

FANTASMAS, RETORNOS, INCERTIDUMBRES. EL CINE DE LA TRANSICIÓN.

El año 2004 se vota en el congreso la ley de financiamiento al audiovisual, una ley largamente esperada por quienes, llevaban, desde hace un par de años, intentando hacer realidad una industria del cine.

Los filmes que configuran una primera formación fuerte dentro de la primera década de democracia (1988-1998), de algún modo deben enfrentarse a un doble desafío: proyectar un interés por la formación de una Industria del cine, atrayendo público a las salas, haciendo visible la viabilidad del cine y, por otro lado, hacerse cargo de los temas sociales y políticos propios del fin de la dictadura y el giro democrático. Imagen Latente (Perelmann, 1988) y el documental de Ignacio Agüero Cien niños esperando un tren (1988), abren un nuevo período en ese sentido, siendo ambas películas que de una u otra manera se sienten como los primeros filmes aparecidos públicamente que tocarán el tema de la dictadura. La primera, una cinta “sombría”, ambientada en un Santiago en plena dictadura, cuenta la historia de un fotógrafo que debe busca pistas de un hermano “desaparecido” por los agentes de la dictadura. La segunda, un documental de carácter observacional y sutil en su trazo, muestra el trabajo llevado a cabo por una profesora (Alicia Vega, además una destacadísima investigadora de cine en nuestro país) con un grupo de niños mediante un taller de cine. Menos directa, pero abiertamente social en su planteamiento, el documental de Agüero tiene en común con la ficción de Perelmann constatar la importancia social de un dispositivo artístico. En el caso de Perelmann se trata de la fotografía, que hacia el final del filme, pasa de ser un instrumento publicitario a tener una vocación por lo real, capturando topográficamente lugares donde se ejecutan torturas. En el caso del documental de Agüero, el cine es comprendido desde una forma más lúdica, pero también transformadora de lo real: en plena dictadura, el cine se vuelve una herramienta importante pedagógica, una forma vinculante de niños que han sido segregados por el sistema económico. Durante los siguientes años, el cine ahondará en ambos temas, por un lado la memoria reciente de la dictadura, por otro, la marginación y desigualdad que parece haber dejado como herencia la dictadura.

Lo primero en tres destacados trabajos: La frontera (Ricardo Larraín, 1991), Amnesia (Gonzalo Justiniano, 1994) y La memoria obstinada (Patricio Guzmán, 1996). La primera, una co-producción hispano chilena que ganará premios en el extranjero (Oso de Plata en Berlín, premio mejor guión en Festival de La Habana), será también muy bien recibida por la crítica local, está ambientada en el desolado paisaje al sur de Chile, y tiene como trama la historia de Ramiro Orellana, un ex militante que es relegado por el regimen a trabajar en esa zona, mediante una imaginativa galería de personajes (un español que estuvo en la guerra civil, una solitaria mujer, un buzo) pero sobre todo en la capacidad de crear imágenes profundas que vinculan la abrumadora y destructiva fuerza del paisaje con la realidad social del país, Larraín crea una obra vigorosa y poética, cercano a lo que quizás hoy podríamos entender por “realismo mágico”. El caso de Amnesia y La memoria obstinada es distinto. La primera es un drama obscuro que cuenta una historia de una venganza contra un torturador (también con tintes de fábula desbordada, tirando al grotesco), el segundo es un documental de uno de los cineastas que más destacada carrera tuvo en el extranjero, y que se dio a conocer al mundo con La Batalla de Chile (1975-1979) documental de tres partes que narra el auge y caída del gobierno de Allende. En La memoria obstinada Guzmán muestra, bajo el testimonio de varias voces (todos ligados por historia o filiación, por exilio o vivencia en terreno) el quiebre con las utopías del pasado y las frustraciones que acarrea, así como las heridas dolorosas dejadas por la violencia política y militar ejercida en el pasado reciente de Chile. Con este film, ampliamente debatido en el marco del debate político cultural de izquierda, Guzmán inaugura una línea de investigación, y junto con él, un tono de acercamiento, que serán los documentales que indagarán en el marco del proceso democrático, en la construcción colectiva de la memoria.

La segunda línea que conforma este primer momento del cine chileno, ligado a retratar, enmarcar o denunciar ciertos cambios profundos en la Transición política y que dió como fruto un curioso Realismo en sintonía con algunas tendencias que surgirán durante la década del noventa en América Latina (Gaviria en Colombia, primer nuevo cine argentino). “Realismo” que debe definirse muy a contrapelo de las tendencias surgidas en la década del sesenta, y que coqueteará con los géneros cinematográficos (del género negro a la comedia dramática y picaresca) y a veces con la crudeza del registro y la violencia. La inaugural fue Caluga o Menta (Justiniano, 1990), que impactó por el retrato crudo del lumpen, hijo de las políticas económicas liberales dejadas por la dictadura, así como por el anuncio de la mediatización televisiva, ambas cuestiones que profundizaráJohnny 100 pesos (Graef Marino, 1994), en el thriller protagonizado por un adolescente marginal donde un grupo de asaltantes se toma un videoclub, y se termina transformando en un suceso mediático, televisivo. La película de Graef Marino es un caso inédito en nuestro país, tanto por su factura narrativa- funciona como un reloj- como por la vocación abierta de hacer un cine comercial con un acertado enfoque social, que habla de los cambios sociales así como las incertidumbres que se presentaban hacia inicios de los ´90. Llegados la década del Dos Mil, ese énfasis político (en la crítica a los medios, en el situar abiertamente los relatos en situaciones de marginalidad) irá perdiendo fuerza y mutando hacia una comedia idiosincrática y popular que en sus mejores momentos (El chacotero sentimental, Galaz, 1999; Historias de Futbol, Wood, 1997; Sexo con Amor, Quercia, 2004) no solo romperá récords de taquilla si no que irá creando- en un nivel institucional- el ambiente propicio para la promulgación de la Ley del cine.

RUINAS Y PUESTAS EN ABISMO

Aquí se construye (2000) de Ignacio Agüero, y Machuca (2004) de Andrés Wood, marcan, en paralelo, y subrepticiamente, movimientos nuevos dentro de nuestro cine. El primero, un documental de observación, del mismo director de Cien niños… registrará la construcción de edificios modernos – y de mal gusto- en los barrios residenciales de Santiago de Chile. Mediante una sutilización del registro geográfico-existencial (el documental sigue a un profesor universitario que será la mirada que intentará comprender la situación), Agüero hace una arqueología topográfica pero emocional de Santiago, encontrando, en el proceso de reconstrucción del neo-Santiago (hijo del neoliberalismo económico) la aparición de densas ruinas y fragmentos que parecen poblar de fantasmas la ciudad. Machuca, por su parte, es una ficción que tiene por protagonista a un niño ambientada en el auge y caída del gobierno de Allende. De gran empatía con el público, la película cumplió, por un lado, con las expectativas de un público deseoso de ver un filme que abordara sintética y emotivamente las biografías y paisajes emocionales vividos entre 1970 y 1973, las fracturas familiares y afectivas propias del período. La película no sólo sirvió para establecer un abierto diálogo social al respecto, si no que a su vez estableció, de algún modo, un “canon” al respecto de la representación de 1973 que está a mitad de camino entre la des-ideologización y el destape público.

El paisaje después del 2004- año de promulgación de la ley- cambia abruptamente. – La Universidad de Valparaíso, Universidad de Chile y Universidad Católica se hacen cargo de abrir carreras de cine, lo que significa, la expansión y establecimiento de una formación de carácter formal del cine.

- El número de estreno de películas había llegado a su Peak el año 2003 con cerca de 30 películas estrenadas, pero desde ahí en adelante, doblando y triplicando todas las cifras obtenidas anteriormente.

- El acceso a cámaras digitales, abarata los costos de producción, lo que permite que se produzcan, e incluso se estrenen películas en formatos digitales

- El surgimiento de decenas de nuevos Festivales que se distribuyen entre la especificidad de sus programaciones – aumentando su calidad y especificidad: cine independiente, documental, patrimonial, underground- y su des-centralización geográfica

- La aparición de un “campo cultural de cine”, entre ellos, la renovada actividad de páginas web de crítica especializada (Fueradecampo.cl, Mabuse.cl, laFuga.cl) y la aparición de Uqbar, una editorial especializada en cine

- Y en los últimos años, la notoria baja de espectadores yendo al cine (fenómeno transnacional), que ha llevado a cuestionar el carácter sagrado del estreno en sala, siendo el año 2008 el año de la “crisis de público” para el cine chileno.

Entre otros factores, influyen en que en los últimos años, el ambiente esté bastante variado. Los formatos, formas y modalidades de representación cinematográfica se establecen hoy, en campos no tan claros: películas documentales que a partir del cuestionamiento de su dispositivo empezaron a abrirse hacia la fragmentación y la reflexividad sobre su lenguaje (Ningún lugar en ninguna parte, 2004; Arcana, 2006; Dear Nonna, 2004), películas sin el límite claro entre lo documental y la ficción (El Pejesapo, Obreras saliendo de la fábrica, Alicia en el país, El astuto Mono Pinochet y la moneda de los cerdos, 2004), la proliferación de un “yo” cada vez más íntimo, literario y confesional en muchos documentales (La ciudad de los fotógrafos, 2006; Calle Santa Fe, 2006; Retrato de Kusak, 2004), y durante los últimos años, una re visitación topográfica, fragmentada y discursiva sobre Santiago (Tony Manero, 2008; Mami te amo, 2008; Tiempos Malos, 2009) nos dejan claro que si bien no es posible establecer un rumbo claro, algunas de las líneas conformadas desde inicios de la democracia continuarán profundizándose (memorias colectivas y sociales) y otras posiblemente tengan que mutar o adaptarse a algunas convergencias digitales (industria del cine), lo que es claro, es que suceda lo que suceda, el cine – el que nos interesa- sabrá hacerse pertenecer a su tiempo, y será necesario, entonces, reforzar los campos culturales de recepción de esas imágenes que nos hablarán a nosotros mismos, posiblemente ya de formas que nos cueste reconocer.

Fall 2009, Volume VIII, Number 3

Iván Pinto Veas is a professor and film critic, with studies in Film, Aesthetics and Communication and culture. He is presently working as developer, editor and critic of the film website www.lafuga.cl.

Iván Pinto Veas es profesor y crítico de cine, con estudios en Cine, Estética y Comunicación y cultura. Actualmente se desempeña como desarrollador, editor y crítico del sitio web cinematográfico www.lafuga.cl.

Related Articles

Coconut Milk in Coca Cola Bottles

Common knowledge has it that virtually any movie, once removed from its original cultural context of production and reception, might be either misunderstood and misperceived or re-interpreted and re-signified. Likewise, we may agree that national cinemas seek to define, challenge….

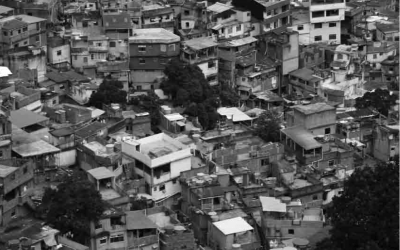

Neither the Sertão or the Favela

To frame the poetics of the ordinary in terms of subtlety and delicateness is to propose an antidote both for cynicism and for what I call Neo-Naturalism. Its appearance, at least in Brazilian cinema and literature, has been clearly identified, ranging from peripheral subjects…

Brazilian Cinema Now

Snow falling in the city of São Paulo, in southern Brazil? Taking a helicopter in São Paulo then arriving a few moments later in the deep wilderness of the Amazon jungle, half a continent further away to the north? Then meeting a white Asian tiger in the heart of the Amazon forest?…