A Review of In the Shadow of Quetzalcoatl: Zelia Nuttall and the Search for Mexico’s Ancient Civilizations

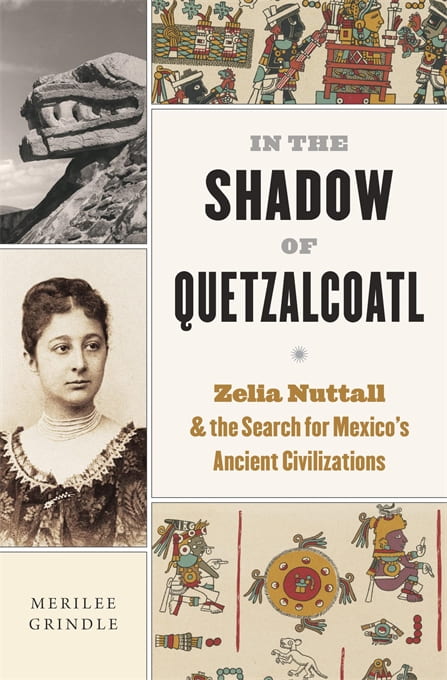

In the Shadow of Quetzalcoatl: Zelia Nuttall and the Search for Mexico’s Ancient Civilizations by Merilee S. Grindle (Belknap Press, 2023, 368 pages).

Nutall’s life and career of the provide a rich and fascinating subject that, to date, has gone largely underappreciated. Nuttall’s work, beginning in the 1880s and continuing until her death, helped shape the field of archaeology and the scientific study of the history of humankind in the Americas during the crucial period in which these disciplines were becoming professionalized.

Grindle situates Zelia Nuttall as a child of the gold rush, from which she derived both her wealth and her adventurous and combative spirit. Born into a wealthy San Francisco family, Nuttall was educated in Europe. In 1880, having returned to California, Nuttall married the French linguist and antiquarian Alphonse Luis Pinart. A passionate collector of books and artifacts, Pinart soon spent the majority of Nuttall’s inheritance on his antiquarian collections. Nuttall filed for divorce just two years after they wed, citing financial difficulties. Revealing the independence of spirit that would characterize her scholarly career, she also sued for the right to retain her maiden name for herself and her daughter.

Striking out on her own, Nuttall began pursuing her scholarly interests in both Mexico and Europe. Frederic Ward Putnum at the Peabody Museum in Boston became her mentor and gave her the title “honorary special assistant” for the Peabody Museum. Putnum also published her essay “Standard or Headdress” to inaugurate the series Archaeological and Ethnological Papers of the Peabody Museum (1888).

In 1902, Nuttall moved to the neighborhood of Coyoacán in Mexico City and conducted her field work and scholarship from there. At this time, she was one of Phoebe Hearst’s compatriots in building the University of California and, in particular, acquiring items for the anthropology museum, which was anticipated to house a significant collection of Mexican manuscripts and artifacts. Nuttall also received a salary from the University of California Crocker Reid fund to compensate her for her time and fieldwork.

Considered an amateur scholar by her university-trained peers, Nuttall nonetheless became an important voice in advocating for professional, scientific standards in archaeology. Grindle’s title, “In the Shadow of Quetzalcoatl,” refers to the moment in 1909 when Nuttall believed she had discovered a site on the Isla de Sacrificios that demonstrated cultural diffusion between Mexica and Mayan people, centering around the shared Mesoamerican deity Quetzalcoatl/Kukulkán. Nuttall applied to the Mexican government for formal permission to excavate the site. This exciting moment in Nuttall’s life became even more dramatic when, in 1910, Leopoldo Batres, the national archaeologist of Mexico, seized the site and forbade Nuttall from working there. Nuttall responded with a series of published attacks on Batres and became embroiled in a contentious debate regarding the application of scientific standards to archaeology in Mexico. This struggle ended in vindication for Nuttall when her cataloging system was eventually chosen over Batres’s system by the National Museum in Mexico.

Grindle excels at framing Nuttall’s life in a way that explains how she was able to organize her personal life and her publications despite frequent traveling. This is a challenge that has daunted anyone who has approached a biography of Zelia Nuttall. Grindle’s biography of Nuttall is the latest contribution to a small but growing body of work on this fascinating figure. The first short biography about Zelia Nuttall was her obituary, penned by the Harvard archaeologist Alfred Tozzer for American Anthropologist in 1933. Tozzer highlights her extensive archival research and delights in her ability to find missing codices and manuscripts, such as the Mixtec Codex Tonindeye (formerly known as the Codex Zouche Nuttall) and manuscripts related to Sir Francis Drake’s expedition to Mexico.

In the 21st century, a handful of scholars have begun to rediscover Nuttall, each concentrating on different aspects of her legacy. Carmen Ruiz’s 2003 dissertation, “Insiders and Outsiders in Mexican Archaeology, 1890-1930,” examines the dynamics of gender, race, and class that informed the rivalry between Nuttall and Leopoldo Batres. In her 2010 chapter “Mexico’s Archaeological Queen: Zelia Nuttall 1857-1933,” for the anthology Ladies of the Field: Early Women Archaeologists and Their Search for Adventure (Greystone Books, 2010), Amanda Adams emphasizes that Nuttall’s involvement in Mexican archaeology derived from her interest in her mother’s Mexican heritage and reviews the role that Nuttall played in founding anthropological studies at the University of California through her relationship with Phoebe Hearst. Apen Ruiz Martínez weaves together the work of Zelia Nuttall and Isabella Ramírez as founders of scientific archaeology in Mexico in Género, Ciencia y Política: Voces, vidas y miradas de la arquelogía mexicana (INAH, 2016), showing how the debates that Nuttall initiated were solidified by Ramírez into archaeological practice.

In my own work, I explore Nuttall’s role as an independent scholar locked in conflict with other archaeologists and argue that these conflicts helped to professionalize the field. In Ornamental Nationalism: Archaeology and Antiquities in Mexico, 1876-1911 (Brill, 2018) and “Zelia Nuttall and the Tonindeye Codex: Recontextualization of a Mixtec Pictorial Manuscript” (Printing History 31/32, January 2023), I focus on the personal networks that Nuttall used to facilitate her work, both as an archaeologist and as a publisher of Mexican codex reproductions, and how her disagreements with other antiquarians led to the development of methodological standards in archaeology.

Each of these writings provides snapshots into Nuttall’s body of work and her life, but a far more comprehensive picture is presented in Ross Parmenter’s monumental, unpublished Nuttall biography, on which Grindle draws extensively. A music critic and independent scholar, Parmenter spent forty years researching and writing on Nuttall, eventually completing “Zelia Nuttall and the Recovery of Mexico’s Past”—a 1,531-page manuscript that he hoped to publish in three volumes. Sadly, Parmenter passed away without finding a publisher, but he amassed an enormous amount of research and primary sources pertaining to her life and career, including a decades-long correspondence with Nuttall’s daughter and other family members. Visitors to Parmenter’s home in Oaxaca have told me that three rooms were dedicated entirely to his research materials on Nuttall. Parmenter’s work is thorough and exhaustive, but modern scholars must read this manuscript critically and be wary of Parmenter’s penchant for romanticizing his subject. Complicating matters, Parmenter choose not to footnote this massive tome, which means that those who wish to verify his sources are required to sort through the 115 boxes of his research notes, housed at the Latin American Library at Tulane University.

In recounting Zelia Nuttall’s life, Grindle relies heavily on Ross Parmenter’s manuscript, but also delves into the archives of Nuttall’s correspondence at the Peabody Museum, the Bancroft Library, the University of Pennsylvania, Smith College, the Smithsonian and the University of New Mexico. In bringing this material to a broader public, Grindle has allowed Nuttall’s vibrant, dynamic personality to emerge.

Grindle places Nuttall in a milieu that included other scientific and philanthropic luminaries such as Frederic Ward Putnum, Charles Pickering Bowditch and Edward Seler, but also stresses how Nuttall surrounded herself with a community of independent, philanthropic and scientific women such as Phoebe Apperson Hearst, Adela Breton, Sara York Stevenson and Alice Fletcher.

Grindle characterizes Nuttall’s work in archives and in the field as the hunt for the history of mankind, and she deftly brings out the drama inherent in such research. “Stimulated by a desire to know more, the curious and intrepid who could find patrons to support their work began to sift through the dust of old libraries, museums, and archives to recover such records. Zelia Nuttall was one of the finest archival detectives of her generation” (p. 300).

As a woman who worked independently but in conjunction with universities, museums and other scholars, Nuttall is an inspiring model. Defying her cultural constrictions, she exerted a significant impact on the values and methodologies of institutions. A striking example is provided by the fact that Nuttall was instrumental in obtaining a scholarship for Manuel Gamio, the future director of the Mexican National Museum, so that he could acquire archaeological training at Columbia University and eventually supplant her rival Batres. In a frank manner, she asked Franz Boas to help Gamio acquire the training he required. Writing to Boas on 27 September 1909, Nuttall stated, “What I hope most is that you should give him [Gamio] a thorough knowledge of Museum work so that someday soon he can be made the Director of the Archaeological Section of the National Museum here and Inspector of Monuments in the place of Batres” (American Philosophical Society, Franz Boas Papers).

Grindle’s biography admirably contextualizes the life of Zelia Nuttall. One hopes that renewed attention to this important figure will result in future work that rigorously reviews and critiques Nuttall’s scientific contributions, acknowledging her ongoing relevance to the history of anthropology in Mexico.

Seonaid Valiant is Curator for Latin American Studies, Arizona State University. Author of Ornamental Nationalism: Archaeology and Antiquities in Mexico, 1876-1911 (Leiden: Brill, 2018) She received her doctorate in history from the University of Chicago.

Related Articles

A Review of Live From America: How Latino TV Conquered the United States

The story of Spanish-language television in the United States has all the elements of a Mexican telenovela with plenty of ruthless businessmen, dashing playboys, sexy women, behind-the-scenes intrigue and political dealmaking.

A Review of The Power of the Invisible: A Memoir of Solidarity, Humanity, and Resilience

Paula Moreno’s The Power of the Invisible is a memoir that operates simultaneously as personal testimony, political critique and ethical reflection on leadership. First published in Spanish in 2018 and now available in an expanded English-language edition, the book narrates Moreno’s trajectory as a young Afrodescendant Colombian woman who unexpectedly became Minister of Culture at the age of twenty-eight. It places that personal experience within a longer genealogy of Afrodescendant resilience, matriarchal strength and collective struggle. More than an account of individual success, The Power of the Invisible interrogates how power is accessed, exercised and perceived when it is embodied by those historically excluded from it.

A Review of Negative Originals. Race and Early Photography in Colombia

Negative Originals. Race and Early Photography in Colombia is Juanita Solano Roa’s first book as sole author. An assistant professor at Bogotá’s Universidad de los Andes, she has been a leading figure in the institution’s recently founded Art History department. In 2022, she co-edited with her colleagues Olga Isabel Acosta and Natalia Lozada the innovative Historias del arte en Colombia, an ambitious and long-overdue reassessment of the country’s heterogeneous art “histories,” in the plural.