About the Author

Jean Vilbert holds a Master’s in Laws (Fundamental Rights) and served as a judge in Brazil, where he teaches Constitutional Law and Humanities. He is currently a Master’s of International Public Affairs candidate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and works as a teaching assistant in the Department of Political Science (Comparative Politics). He is also a Fellow at the Latin American, Caribbean and Iberian Studies Program (Lacis).

Active Free Media is More Important than ever in Brazil

In Brazil, my home country, President Jair Bolsonaro has been at continuous war with the media, denouncing any unfriendly press coverage as “fake news.” To my surprise, I recently learned that many Brazilians cheer up when Bolsonaro excoriates reporters—a widespread perception in the country that the media is too partial and even manipulative, a lost case. Hearing the noise from the streets, I can attest that some believe journalists are getting what they deserve.

“15/05/2019 Presidente da República Jair Bolsonaro fala com a imprensa” by Palácio do Planalto is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

I am far from stating that the media always merits unconditional praise. Actually, we can draw examples from Latin America to show that citizens should be open-minded but critical about what is broadcasted on prime time: when former Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori was arrested in 2005, it was discovered that he had bribed the country’s barons of the media for years to prevent that his abuses were reported and to sustained the facade of democracy.

However, there are strong reasons to assert that supporting hostilities against the press is not the solution at all. On the contrary, it is a big mistake.

From a philosophical perspective, as John Stuart Mill emphasizes in his important work “On Liberty,” even when true, opinions are seldom or never the whole truth. “Only through diversity of opinion is there, in the existing of the human intellect, a chance of fair play to all sides of the truth”. The media is exactly the vehicle through which different views reach broader audiences. Often, these standpoints include annoying stances to those in power. And then, instead of using legitimate tools to question what they believe to be mistaken, some political leaders think repression is an easier road, which unfortunately is not unusual in Latin America.

The point is, if the information broadcasted in the media is not accurate, a national leader has all the instruments to tell his/her version of the facts, which do not comprise attempts to silence criticism and empty-direct confrontation through rough words, disregarding diplomacy and century-long western efforts to contain anger in the public speech.

In this regard, most Americans were probably surprised when then-President Donald Trump raised his voice against the so-called “fake news” media. Sadly, this is also not something new for us Latin Americans; both in Brazil and neighboring countries, the chorus “imprensa golpista” (pro-coup press) has been around for decades. Indeed, many populist leaders, such as Hugo Chávez, used such a motto to gain political leverage and as an excuse to crush the opposition.

This brings us to my second point, a political one: the ability of political leaders to tolerate criticism, opposition, and (irritating) contrary viewpoints is a clear indication of democratic commitment, or otherwise the lack thereof. Societies that are able to bear with high levels of oversight and respectful disagreement—two of the main roles of the media—are precisely those in which democracy thrives and the res publica (public interest) is better protected.

An interesting anecdote can help me make this case. In the 1990s, researchers Reinikka and Svensson revealed that out of the money sent from the Ugandan government to its schools only 13 percent were ever invested in education—most of the funds ended up in the pockets of district officials. By 2001, the researchers repeated the experiment and found quite different results: schools were getting more than 80 percent of the money they were entitled to. What has changed? Newspapers had started to report month-by-month where the money was being spent. With journalists on the watch, the officials’ binge had come to an end (Banerjee and Duflo – Poor Economics). Corruption is facilitated where the media is weak and the opposite is true likewise, wherever the media is vibrant, corruption is a particularly risky business.

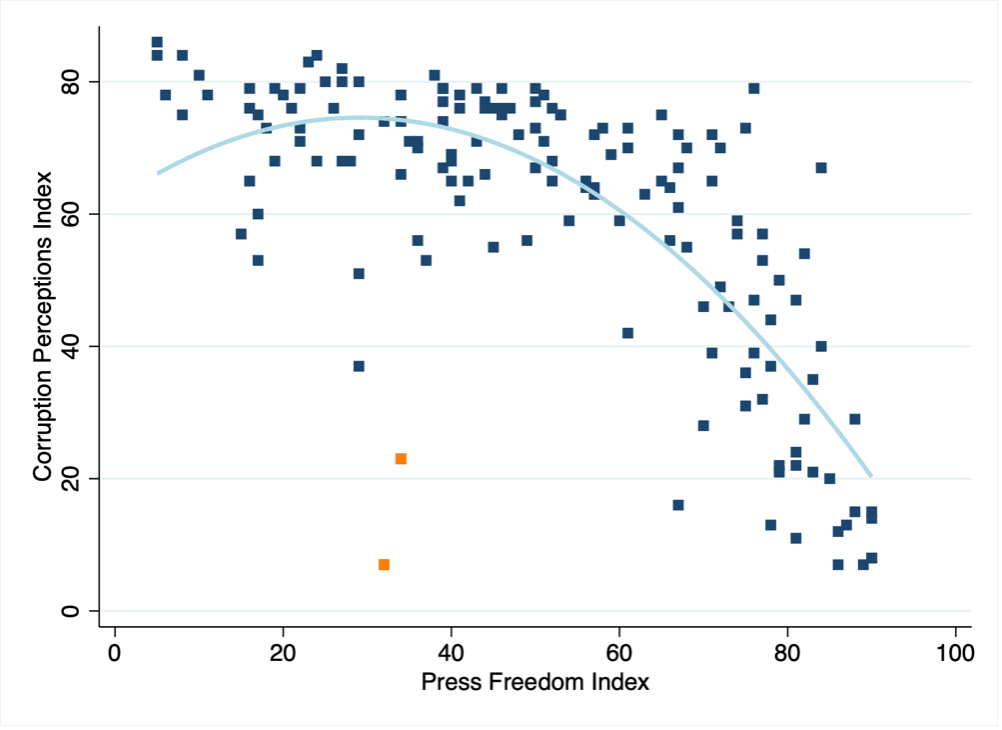

Expressing this relationship through quantitative data, the graph below displays the strong negative correlation between freedom of the press and levels of corruption, that is, the more the media is free in a country, the less corruption tends to flourish.

Source: Author’s research with data from Transparency International and Freedom House

Therefore, even if on certain occasions there are fair reasons for dissatisfaction with the quality of the press coverage, it would be a mistake to support politicians who go after the media when criticized. A free press, which side-effect may be a certain dose of bias here and there, is like that old bicycle—the one you complain and complain about until it gets a flat tire. Just then you sees how useful that old pair of wheels was, regardless of its flaws.

In 2022, Brazil will be still struggling to recover from a pandemic that already fueled a stronger grip over information that one could call soft censorship. Moreover, the country is entering an electoral year in which voters will probably have to choose between the abyss and the cliff: Jair Bolsonaro and Lula da Silva, two politicians with anti-democratic traits and a clear desire to keep close tabs on the press—when president, in 2004 Lula tried to pass a law that would impose robust political control over the media — let alone the suspicions of corruption that threaten both Bolsonaro and Lula. Thus, more than ever, Brazil needs free and active press so that Brazilians can make an informed decision and check their next president. The future of my country may depend on how effectively the media operates during these troubled times.

More Student Views

Puerto Rico’s Act 60: More Than Economics, a Human Rights Issue

For my senior research analysis project, I chose to examine Puerto Rico’s Act 60 policy. To gain a personal perspective on its impact, I interviewed Nyia Chusan, a Puerto Rican graduate student at Virginia Commonwealth University, who shared her experiences of how gentrification has changed her island:

Beyond Presence: Building Kichwa Community at Harvard

I recently had the pleasure of reuniting with Américo Mendoza-Mori, current assistant professor at St Olaf’s College, at my current institution and alma mater, the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Professor Mendoza-Mori, who was invited to Madison by the university’s Latin American, Caribbean, and Iberian Studies Program, shared how Indigenous languages and knowledges can reshape the ways universities teach, research and engage with communities, both local and abroad.

Of Salamanders and Spirits

I probably could’ve chosen a better day to visit the CIIDIR-IPN for the first time. It was the last week of September and the city had come to a full stop. Citizens barricaded the streets with tarps and plastic chairs, and protest banners covered the walls of the Edificio de Gobierno del Estado de Oaxaca, all demanding fair wages for the state’s educators. It was my first (but certainly not my last) encounter with the fierce political activism that Oaxaca is known for.