A Review of Adiós Niño: The Gangs of Guatemala City and the Politics of Death

Dying to Become a Gangster

Adiós Niño: The Gangs of Guatemala City and the Politics of Death By Deborah T. Levenson Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013, 200 pages

The phenomenon of maras (gangs) has become prevalent and pervasive in Guatemala. As one example, during a Kaqchikel Maya language and culture course I co-directed in 2013, one native speaker drew an image of the devil with M-18 written across his forehead to demonstrate the Kaqchikel word for bad/evil (itzel). Referencing the Mara-18 or Calle-18 gang that terrorizes some Guatemala City neighborhoods and operates in other urban and rural areas of Guatemala, the image immediately resonated with the other native speakers and Guatemalan students in the course. Kaqchikel teachers resent maras‘ extortion in their central highland communities, but are grateful these groups have not yet deployed violence to achieve their goals.

Judging from Deborah Levenson’s new book, Adiós Niño, the mara experience in the capital is decidedly different from that in the rural highlands, and also more complicated than the way the media (Guatemalan and foreign alike) portray it. Even as she documents the lethal acts of M-18 and their counterparts in Guatemala City, Levenson posits that the terror associated with these gangs has been exaggerated and leveraged by elites, politicians, and narcotraffickers to secure their positions of power.

One of Guatemala’s tragic paradoxes is that crime—particularly violent crime— has actually increased since the signing of the 1996 Peace Accords that ended the nation’s 36-year civil war commonly referred to as la violencia (the violence) or el conflicto armado (the armed conflict). For most Guatemala City residents, life has become more dangerous since the cessation of the war. By pointing to the ways maras are both part and pawns of larger forces that use violence to perpetuate their power, Levenson makes a valuable contribution to the vast literature on violence in Guatemala (the very proliferation of which points to the nation’s turbulent past and unstable present).

As the M-18 devil image suggests, street crime in Guatemala is frequently attributed to the maras. By immersing herself in the world of the Guatemala City maras, Levenson does not so much dispute this assertion as historicize it: she reveals how the maras changed dramatically from the 1980s to the late 1990s. Associated with disorder since the 1980s, the maras only recently turned to violent crime.

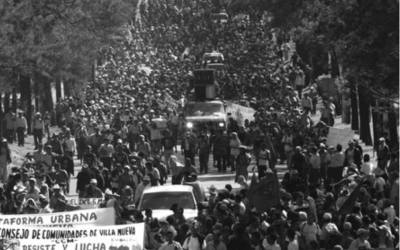

Emerging in the mid-1980s in response to the austerity measures of neoliberal economic reforms applied in many Latin American countries, the Guatemala City gangs of the 1980s provided an outlet for urban youth’s angst and frustration with the government. Far from undermining civil society, these groups aimed at buoying its ability to respond to elites, politicians, and generals who sought to consolidate their own power and wealth at the expense of the poor and working and middle classes. As the Guatemalan military ostensibly released its iron grip on politics in the mid-1980s and opened the space for public protest by heralding (if not implementing) a transition to democracy, some gang members envisioned themselves as modern-day Robin Hoods. To be sure, gang members extorted working-class people too, but their actions originated in political activism rather than in the culture of death that came to define the gangs of the late 1990s. Most members participated in the maras for a few formative years before moving on with their lives; few allowed the gang experience to define them. In contrast, as the marastook a violent turn in the late 1990s, most members joined them for (a tragically short) life.

Descriptions of the ferocity that characterized gang life in Guatemala City and the prison system make the second half of the book haunting. With her trademark transparency, Levenson explores how the methodological challenges of conducting oral history research with recalcitrant informants shaped her project. When she resumed her research in the late 1990s, many gang members refused to talk to her. For young men and women whose average life span was 22 years and for whom death was a constant companion, conducting an interview was not only pointless but counterproductive. Conditioned to remain silent, one young man told her, “To talk is to die” (89). Levenson admits, “It was impossible for me to conceptualize how to ‘interview’ anyone who did not want to talk.” Her persistence paid off, however, as “the difficulties of having conversations started to become its own topic” (89). As a few gang members opened up and she sought interviews with those who were trying to leave or had left the gangs, she learned of a complex culture of death that permeated the lives of gang members, some of whom were as young as five years old. She also uncovered raw emotions under tough exteriors. One ex-gang member, Rosa, admitted to “feeling bad” and suicidal after killing an elderly woman whose grandchildren were part of a rival gang. In a tribute to Levenson’s even-handed approach, readers may be surprised to find themselves empathizing with murderers.

Documenting the pitfalls as well as the breakthroughs of working with those outside the law and at risk makes Adiós Niño particularly valuable for students who often approach books as inevitable validation of research rather than processes marked by fits and starts. Offering a window into the rewriting and revising process, Levenson quotes one reviewer’s critique of her manuscript and then responds to it.

The book’s penultimate chapter explores prisons as sites of gang rivalries, identities, communication, and power. Struggling for control, incarcerated gang members fight not so much to escape from prison but rather to expand their control inside it. These struggles pit them against prison personnel and against imprisoned authorities (military and civilian alike) whose main concern is controlling and profiting from the prison that houses them. To understand these complex relations and gangs’ broader significance, it would have been helpful have a sense of how these gangs operated and what their long-term goals were, beyond the snapshots of individual violence and criminal activity that Levenson so richly documents. According to other studies, the M-18 and other gangs have developed sophisticated organizational charts and strategic plans that guide and inform their work in the United States, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Venezuela, Peru and elsewhere. Exploring maras’ meta-structures and goals would have provided a keener sense of how they operate internally and internationally, and how they seek to position themselves within the larger milieu of Guatemalan society and economics (albeit illicit).

In other ways, Levenson adeptly broadens the context of her study. Exploring Guatemala City residents’ responses to the mara phenomenon, Levenson reveals that even Guatemalans desperate enough to call for strong-armed responses to maras do not necessarily blame individual mareros for their way of life. Violence begets violence but does not eradicate compassion. At the same time, those professing to help troubled youths are not necessarily altruistic. Hired by the Christian conservative president Jorge Serrano Elías (1991-1993), one Pentecostal organization physically abused boys in their care and tried to force their conversion. More than an ethnographic study, Adiós Niño explores the broader political, social, economic and historical contexts surrounding the creation and perpetuation of the maras in Guatemala City.

Less than 200 pages long, Adiós Niño is a concise and riveting read. Levenson’s prose is engaging and the stories are gripping. Yet some arguments remain undeveloped. Undoubtedly, it is difficult if not impossible to provide empirical evidence for the argument that forces larger than maras use them and benefit from a “micropower of death” to perpetuate their power. Yet concluding the book with the story of ex-gang members who were gunned down while trying to rebuild their lives, and suggesting in a few sentences that the killers were not related to the gangs but rather to the powers that be, left this reader intrigued but not convinced.

These critiques notwithstanding, with this, her second book about Guatemala City, Levenson makes a valuable contribution to Guatemalan scholarship that is largely dominated by rural studies of Maya peoples and to the historiography of urban Latin America more broadly.

Winter 2014, Volume XIII, Number 2

David Carey Jr. is a Professor of History and Women and Gender Studies and Associate Dean of the College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences at the University of Southern Maine. The author of Our Elders Teach Us: Maya-Kaqchikel Historical Perspectives, Ojer taq tzijob’äl kichin ri Kaqchikela’ Winaqi’ (A History of the Kaqchikel People), Engendering Mayan History: Kaqchikel Women as Agents and Conduits of the Past, 1875–1970, his most recent book is I Ask for Justice: Maya Women, Dictators, and Crime in Guatemala, 1898-1944. He also edited Distilling the Influence of Alcohol: Aguardiente in Guatemalan History and Latino Voices in New England (with Robert Atkinson).

Related Articles

Making a Difference: Building Blocks

Since the first, unplanned visit of a Brazilian entrepreneur in 2011 to Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child, a diverse group of professors, practitioners, civil society leaders and other committed individuals at Harvard and in Brazil have…

Travails of a Miner, VIP-style

English + Español

Sergio Sepúlveda is a Chilean miner with an enviable salary—equivalent to that earned by a university-educated professional. He owns a brand new Korean-made car, and every three years…

Indigenous People and Resistance to Mining Projects

English + Español

Latin America’s governments and its indigenous peoples are clashing over the issue of mining. Governments, motivated by economic growth, have established legal frameworks to attract foreign investments to extract mining resources. When those resources are located in…