Adventures in Public Sculpture by a Cruise Ship Lecturer

Exploring Issues of Emancipation in Public Monuments

Laura Facey Cooper Emancipation Sculpture

I have the great fortune to lead a double life as a lecturer in History of Art and Design. For most of the year I teach my subject at Liverpool John Moores University in the United Kingdom, but during vacations it is my privilege to provide lectures to cruise ship passengers on board luxury vessels.

Some people believe that cruise ships exist primarily to allow guests to overindulge in food and drink while they enjoy waterslides, pool competitions and bingo in the sun. However, this is not my experience. I have been able to travel to exotic locations like the Caribbean, which will be my focus here, or Myanmar, Indonesia or the Philippines. In these places, I have been able to encounter lesser-known art works, and thereby enhance my knowledge and understanding of global art history. My role on board cruise ships is to offer lectures in art history to passengers who also want to explore the art and design of the locations they will be visiting. I have found my audience to be educated and curious, looking for a deeper integration into the destinations of their cruise.

Azamara in the Hong Kong Harbor, 2015.

In the process, I’ve also made my own discoveries about public sculpture in the Caribbean region, with a specific focus on monuments relevant to emancipation from slavery. Public sculpture has been a hot topic over the last few years and a focus for debates around the Black Lives Matter movement. In the city of Bristol in the United Kingdom, the 19th-century statue of slave trader Edward Colston was pulled down by the public following the news reports from the United States of the murder of George Floyd in May 2020.

Around the country—and indeed around the world—people were debating and protesting about what was to be done about statues. For example, many monuments to Christopher Columbus have been destroyed or removed in cities in the United States and Latin America; the 1813 statue of Admiral Nelson was removed in November 2020 from the National Heroes Square (formerly Trafalgar Square) in Barbados.

These events have encouraged me as an art historian to consider further the role of public sculpture in the Caribbean region, which of course suffered the heinous yoke of slavery and the cruelty and abuse of the landowners. As a consequence of the European cultural tradition of memorialization by statue, many of these slavers, or other colonial figures, erected public monuments to themselves or were flattered by commemorative sculptures being erected by others in their memory. In 2021, these monuments now offer different meanings to their viewers, which makes them a fascinating subject when visiting Caribbean islands for an educative cultural experience by ship.

As we travel to Jamaica, for instance, we find in Spanish Town Sir John Bacon’s The Rodney Memorial (1789), a typical example of a colonial monument. The subject is Admiral George Rodney (1732-1792), famed for his role in the U.S. War of Independence. He presided over “the Battle of the Saintes,” which foiled a planned invasion of Jamaica by the French and Spanish on April 12, 1782. This marble statue depicts Rodney under a temple-like cupola as a Roman general, holding a baton, shield and sword, and flanked by two cannons of 1748, which were captured from the French vessel, Ville de Paris. The original design for the pedestal of the sculpture included a jingoistic representation of Britannia in a chariot drawn by sea horses and a female personification of Jamaica. This work, authorized by the Assembly of Jamaica, led to ten further commissions of similar imperialist sculptures in Jamaica for the prestigious British artist.

I find it ironic that the statue stands in what has been known since 1997 as Emancipation Square in Spanish Town: a work which commemorates the individual who ensured that Jamaica remained under British control at a critical point in 1782. Indeed, this demonstrates how the interpretations of the sculpture have altered over time. In 1789 the Jamaican government, under British control, were pleased to spend £2,100 on a sculpture and £14,259 on the enclosing temple which, as Matthew J. Smith states in the journal Slavery and Abolition, “inscribed on the city’s urban scape a history of imperial superiority.” However, as early as 1821, visiting writer, Edouard Montule, found it to be anachronistic and divested of “every thing historical” in its use of Roman costume.

In the 1870s, the seat of government in Jamaica was moved from Spanish Town to Kingston, and the Rodney memorial was transplanted to the new capital. Nevertheless, by the end of the 1880s, the statue was returned to Spanish Town. Reports exist that Spanish Town locals had mourned the loss of their Rodney memorial and staged demonstrations, and even a pointed mock funeral during which an empty coffin was sited under the temple that had formerly held the statue. Therefore, it is interesting that, despite its imperialist meanings, the sculpture of the white purveyor of empire was invested with a new reading by the Spanish Town Black residents near the end of the 19th century. As Edgar Mayhew Bacon and Eugene Murray Aaron recounted in The New Jamaica of 1890, the authorities “had taken away the government; they had destroyed the prestige of the place; they had robbed it of its business; and now they had multiplied injury and insult by carrying off Rodney.” In the demonstrations as a response to the diminishment of Spanish Town, the locals saw the sculpture as central. Once it was returned, it was perceived by citizens as an example of their successful campaign to restore something of Spanish Town’s heritage as the heart of Jamaica.

Today, the perception of the sculpture has reversed. It is representative of the oppression and suffering endured by Jamaicans at the hands of colonial occupiers. However, it is an interesting example of how the meaning of a sculpture can alter depending upon the context of the moment.

My cruise ship travels have also led me to Jamaica’s capital city, Kingston, where I have learned more about public sculpture in another location that references Jamaican Emancipation. Laura Facey Cooper’s Redemption Song (2003), in Emancipation Park, Kingston, has received multiple readings that demonstrate how the meanings of sculptures are mutable. In 2002, the Jamaican National Housing Trust developed Emancipation Park in central Kingston to provide a focus for the annual Emancipation Day celebrations, as well as having a year-round role in reminding visitors about the critical moment in Jamaica’s history that was the official ending of slavery in 1838.

Following a sculpture competition, established Jamaican artist Laura Facey Cooper, was awarded the commission, and her vision consisted of two large naked bronze figures, male and female, standing proudly and looking upwards to the sky. The stately figures stand in a pool of water and are not touching. Cooper named her sculpture after the famous track, Redemption Song, (1980) by Bob Marley, itself inspired by phrases made famous in a 1937 landmark speech by political activist Marcus Garvey.

Emma Roberts giving a lecture, Viking, 2017.

Therefore, one would imagine that the credentials of the sculpture are impeccable: it is a work by an established Jamaican artist, depicting humans freed from specificity, and reflecting esteemed cultural and political references. However, immediately, the sculpture was dogged by controversy. The fact that both figures are of well-endowed proportions led some authors, for example, Carolyn Cooper in Small Axe (8) journal of 2004, to state that it reinforces racist ideas of Black hypersexuality. Similarly, some critics commented that the nudity of the figures was not liberating, but instead reminded viewers of the humiliating stripping slaves of clothes by their captors. As sociology professor Winnifred Brown-Glaude cites in Size Matters: Figuring Gender in the (Black) Jamaican Identity, the Jamaican poet Mutabaruka “read the figures’ nudity as symbolizing black subjugation: blacks being stripped of their agency. This representation runs counter to an image of emancipation where black subjects exercized autonomy and power.”

Much criticism was also leveled over the commission because of Cooper’s class and skin color. In a letter quoted in The Guardian, one critic stated, “But in the complex race-colour-class network that governs Jamaica she is neither the right race, the right colour nor the right class… The implication is that black people in Jamaica are incapable of representing themselves.” Cooper is the daughter of the founding chairman of the National Gallery of Jamaica, and has the privileged life of a practicing artist, which seemed to some to position her outside of the appropriate demographic for an artist who explores the impact of slavery on the nation. Furthermore, her skin color appears to be that of a white person, even though she is actually an eighth-generation Jamaican, whose ancestors include Black slaves. Nevertheless, this did not cohere with the impact of the drive around the period of the sculpture’s installation, led by Jamaican Prime Minister, P.J. Patterson, for nation-building efforts to develop in young people “a healthy sense of their blackness.”

However, in my own visits to Emancipation Park, there is now no apparent sense of the former controversies. The Redemption Song sculpture seems to be embraced by citizens who enjoy the park daily. The official Emancipation Park website promotes the sculpture by stating, “Perhaps the most endearing feature at Emancipation Park is Redemption Song… Redemption Song truly represents the spirit of freedom. A freedom to Hope, to Excel and to Be.” Furthermore, the Jamaican government consistently has maintained its support of Cooper and her key sculpture. In 2004, Cooper was recognized by the Jamaican government for her role in the arts by being awarded an Order of Distinction in the rank of Commander. She has represented Jamaica frequently in international biennale and art events over the last two decades.

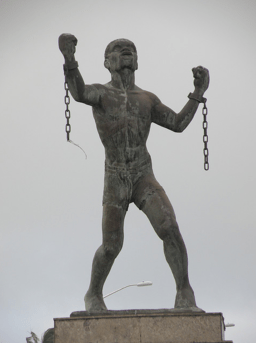

When moving from island to island conveniently by cruise ship, I have been able to explore further the topic of public sculptures that reference emancipation by visiting Barbados. Here, I found Slave in Revolt (1985), also called the Emancipation Monument, or Statue of Bussa, by Karl Broodhagen (1909-2002), located notably at St. Barnabas roundabout on a major highway.

Bussa Statue

Similar to Cooper’s Jamaican Redemption Song, the original nudity of Broodhagen’s Slave in Revolt did not sit well with some. The artist recalled that originally he intended to display the figure as nude, but that this was stymied: “I thought it would be more universal if it were naked, but then the politicians… said that I must put on the pants.” After the artist added some modest shorts, the sculpture also came under criticism for being of a lone male and therefore omitting the role of women in the abolition of slavery. For example, some referenced Hilary Beckles’ 1989 book, Natural Rebels: A Social History of Enslaved Black Women in Barbados, which recounted the active role of women.

Broodhagen’s monument was commissioned by the National Cultural Foundation of Barbados to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the end of slavery in the country. It was intended originally to represent the experience of all former slaves: “a figure that would depict the black man ecstatic in freedom… the ecstasy of pain and anguish for the years that separated him from even that freedom.” He is shown, with a motion of great strength, as having just broken free from his chains of enslavement. However, the populist view of the sculpture has been that it represents specifically Bussa, a slave who died leading the largest slave rebellion in the history of Barbados in 1816. He is now one of the ten official National Heroes of Barbados. Despite the fact that Bussa was not the original subject of the work, it became formally associated with Bussa after 1987, when a so-called Bussa Committee was formed to “challenge the continued tradition of black economic powerlessness.”

Rodney Monument

However, associations were also being made popularly between Bussa and the sculpture immediately upon inauguration. Many writers, such as David Lambert in Patterns of Prejudice journal, comment that Bussa appealed as he was a “surrogate for Africa and African-ness” in the “much less ‘Africanized’ culture in Barbados,” which again reminds one of the simultaneous desire to instil “Blackness” in Jamaica, which was problematic for Cooper’s sculpture. These several interpretations of Slave in Revolt evince that the sculpture is seen simultaneously as a monument to abolition of slavery and to a specific instance of slave resistance.

Once more, this sculpture, along with the other controversial examples considered here, demonstrates how representations of individuals and concepts are not fixed, but that the viewing public overlays such images with meanings of their own. My travels on ship as an art history lecturer have taught me to concur with Laurence Brown, who states in “Monuments to Freedom, Monuments to Nation: Politics of Emancipation and Remembrance in the Eastern Caribbean,” “Often neither the artist, nor the State, nor the public has been able to impose their vision wholly on the monument itself, which has always been read as a work of history in different ways by different social groups.”

Spring/Summer 2021, Volume XX, Number 3

Emma Roberts gained her doctorate from the University of Liverpool in the United Kingdom. She is Associate Dean for Global Engagement and Head of History of Art and Museum Studies at Liverpool John Moores University. Roberts is author of several publications, including the forthcoming Art and the Sea. (2021, Liverpool University Press).

Related Articles

The Eye that Cries: Peru’s Unreconciled Memories

English + Español

In Lima, Peru, in the midst of Campo de Marte, a public park named after the god of war, a Zen space for reflection is guarded by a cast iron fence. El Ojo que Llora (“The Eye that Cries”…

Editor’s Letter: Monuments and Counter-Monuments

Cuba may be the only country on the planet that sports statues of John Lennon and Vladimir Lenin. Uruguay may be the first in planning a full-fledged monument to the victims of the Covid-19 pandemic.

A Monumental Battle for the Story of Texas

In 2016, I visited the Alamo, as part of my first real return to Texas in many years. I had mapped out a road trip with my brother Edmund Roberts. Though Edmund has long known of…