Black Aesthetics and Afro-Latinx Hip Hop: “I’m an African”

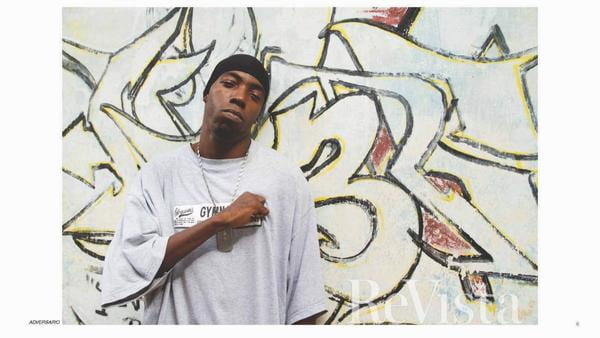

The U.S. emcees from the group dead prez rapped, “I’m an African, I’m an African,” in front of a crowd of thousands at the 1999 Cuban hip hop festival. The amphitheatre resounded with the thundering response of the Cuban audience chanting back the words. It was Pan-Africanism in motion.

The politics didn’t always translate, however. Unaware of the implications of what he was about to do, rapper M-1 pulled out a dollar bill on stage, and began to burn it with a cigarette lighter, an act considered illegal and a defacement of property in the United States. “Because of this dollar, the children in my country are dying for crack, or for drugs, or for bling bling.”

The audience became furious. How could he be burning a precious dollar bill? “Oye, no, gimme that dollar, I can buy some bread, or some french fries,” people in the audience cried out. Then he began to burn a ten dollar bill. “Nooooo! Stop!,” screamed the audience. “What is that crazy guy doing? I could feed my whole family for a month with that.” One member of the U.S. delegation, Raquel Rivera, was translating, explaining to the baffled audience that in the United States black people are dying because of the dollar bill. “But here in Cuba,” shouted one person, half-seriously, “people are dying of hunger.”

Incidents like these lead me to wonder: Can hip hop—a subculture that includes rapping, d-jaying, beat-making, and graffiti writing and a dance form known as b-boying—forge political alliances between Afro-Latinx and Afrodescendant people across the world? Is there such a thing as a global hip hop generation and could it act politically?

HOW HIP HOP WENT GLOBAL

Hip hop is the contemporary expression of African-based dance and music that empowers local youth and subverts dominant orders. Hip hop became global both through the commodification of hip hop culture and what the dance scholar Halifu Osumare calls an Africanist aesthetic that includes complex rhythmic timing, rhetorical strategies, and multiple layers of meaning.

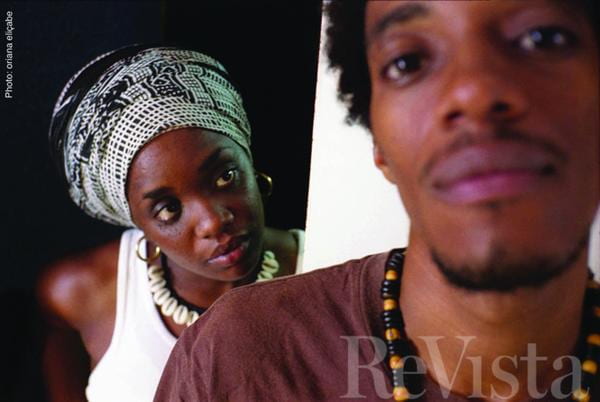

Many emcees had their start as b-boys or b-girls, as the dancers in hip hop culture are called. Growing up in the ‘80s, the Cuban rapper Alexey from the rap duo Obsesión was attracted by the raw energy and soul of the hip hop music he heard on 99 Jams FM, broadcasting from ninety miles away in Miami. As a kid he would build antennas from wire coat hangers and dangle his radio out the window, “crazy to get the 99.” On episodes of the music-dance television program Soul Train on television from Miami, Alexey saw b-boying for the rst time. He copied the steps and then showed them to the kids in the neighborhood. Alexey remembered the gatherings in the El Quijote park. Kids would form a circle, and in the center the b-boys would polish the concrete with their back spins and windmills, while others broke into a beatbox or rhymed.

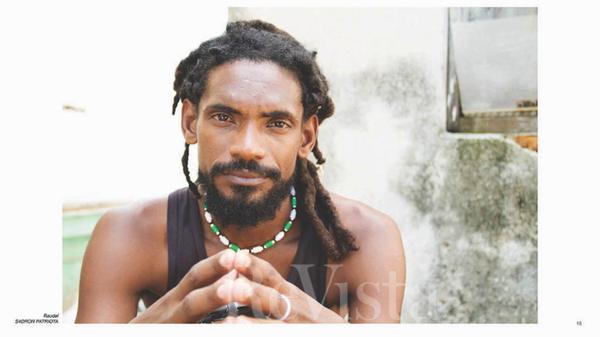

Julio Cardenas, known as El Hip Hop Kid, was an emcee from the Alamar housing projects, just outside of Havana. Julio was raised by his mother in the neighboring sector of Guanabacoa. As a kid, he would come rushing home from school to watch the b-boys “retandose”—battling—and “tirando cartones”—laying out the cardboard strip—on the back patio of his building. They watched bootleg copies of the hip hop films Beat Street, Fast Forward, Breakin’ and copied the moves. Julio moved to Alamar in the 1980s at the age of fifteen, where he became caught up in the hip hop movement that was taking the black and working class community by storm. He would go to the moños, or block parties where people rapped and djayed.

Julio went on to technical college to do a degree in civil construction, graduating at the height of the economic crisis of Cuba’s “special period.” There were no jobs so he went to work with his grandfather in the nearby shery for some cash to help out his mother and to get the local authorities off his back. The local police had a tendency to harass youth, especially black youth, who were not working full time. Eventually he found a job as a bridge operator, raising and lowering the bridge that connected Alamar and Cojimar, to allow the ships to pass through. The job was a no brainer. At 7 a.m., Julio would raise the bridge and by early afternoon when all the boats had gone through, he would sit back with his friends exchanging news about who had the latest rap magazine from the States, and who had heard this song from the rap groups Pharcyde or EMPD.

In ’96, Julio formed the group Raperos Crazy de Alamar (RCA) along with Carlito “Melito,” a carpenter, and his friend Yoan. They started out just to amuse themselves, without ambitions of being serious artists. “That moment we were living was so critical, so boring,” related Julio. “Everything was closed off and censured. We, the youth, were doing hip hop just to do something, looking for a way of having fun.”

The rap scholar Tricia Rose identified this need to break the cycle of boredom and alienation as one of the factors that underlay the rise of hip hop in its birthplace, the Bronx. While Cuba presented quite specific conditions of economic crisis combined with political restrictions, this existential void wasn’t something peculiar to Cuba. Hip hop was a way out of the boredom. It wasn’t the same boredom that kids in the suburbs experienced, wanting reprieve from their sheltered existence. It was the boredom of low-paying, menial jobs and truncated opportunities. And hip hop wasn’t just a distraction from the void. It was a way of recreating a sense of community and finding spaces of pleasure in the face of isolation and the regimentation of life. By the mid-1980s, the elements of graffiti and b-boying were in decline. Rap emerged as the central means by which hip hop culture was packaged for global consumption. At this time, rap movements also began to develop in various countries. Young people rhymed on street corners, using their voices to make a background beat, known as a human beat box. As more serious rap crews began to develop, they realized that they needed digital beats, which often required expensive equipment.

Because of the U.S. embargo against Cuba, Cuban rappers lacked samplers, mixers and albums. But like their Bronx counterparts who developed the sound system from abandoned car radios and made turntable mixers from microphone mixers, global hip hoppers adapted materials from their local environment.

Cuba’s first hip hop DJ Ariel Fernández improvised a set of turntables with old-school portable cassette player Walkmans as the decks, simulating a mixer by using volume controls. Producers drew on a rich heritage of Afro-Cuban music and Afro-diasporic instruments to make their beats. They recreated the rhythmic pulse of hip hop with instruments like the melodic Batá drums. In the heavily Afro-Cuban-influenced eastern provinces, Madera Limpia rapped live with an entire ensemble of Cuban instruments. Obsesión used instrumentation to evoke the era of slavery. In their song “Mambí,” the gentle strumming of a berimbau, a string instrument associated with Afro-Brazilian capoeira, and water sounds produced by the traditional palo de agua give the sense of being near a river or stream, which evokes the rural roots of slaves.

THE LATINX-AMERICAN-CUBAN CONNECTION

Julio and Alexey, like other Cubans of the hip hop generation, had little or no memory of the early years of the revolution. They’d heard stories from their parents about the literacy campaign that mobilized one and a quarter million Cubans, or about the desegregation of whites-only spaces during the 1960s. As the younger generation, they had benefited from the extension of education, housing, and health care to black families. But they came of age during the crisis of the post-Soviet period, as the revolutionary years gave way to times of austerity, and racism was visible once again.

In a society where it was taboo to talk about race publicly, racism was the elephant in the room that everyone knew existed, yet everyone pretended wasn’t there. Fidel Castro had attempted to create a color-blind society, where equality between blacks and whites would make racial identifcations obsolete. But while re-drawing the geography of Cuba’s racial landscape, the state simultaneously closed down Afro-Cuban clubs and the black press. As racism became public once again during the special period—it had never really gone away—black people were left without the means to talk about it. When called on their racism, officials trotted out the same tired line—en Cuba, no hay racismo (in Cuba, there is no racism). But black youth were harassed by police and asked for ID. They had a harder time getting jobs in tourism than their white peers.

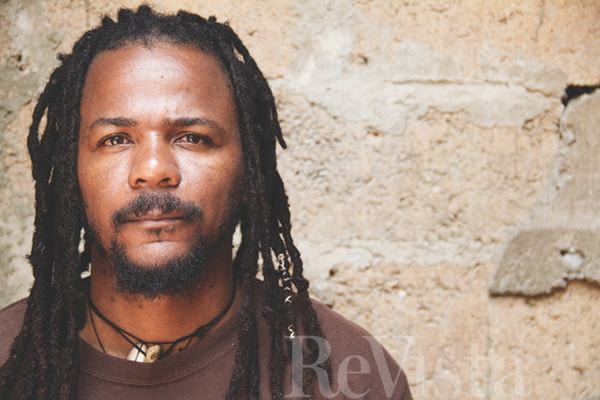

It was into this juncture that hip hop culture appeared and took root. While the black nationalism espoused by an earlier generation of visiting black radicals like Marcus Garvey or Stokely Carmichael never had much appeal in Cuba, African-American rappers spoke a language of black militancy that resonated with Cuban youth. It spoke to their experiences of racial discrimination in the special period. Young Cubans of African ancestry proudly referred to themselves as black. Cuban emcee Sekuo Umoja from Anónimo Consejo told me, “We had the same vision as rappers such as Paris, who was one of the first to come to Cuba. His music drew my attention, because here is something from the barrio, something black. Of blacks, and made principally by blacks, which in a short time became something very much our own, related to our lives here in Cuba.” The U.S. rapper Common organized a meeting with local rappers in which they exchanged ideas and stories. The transnational Black August Hip Hop network brought equipment and records for the Cuban rappers.

The Song “Tengo” (I Have) by the group Hermanos de Causa presents the resurgence of racism in the contemporary period in striking contrast to the post-revolutionary euphoria of Afro-Cubans, who saw in the Cuban revolution the possibilities of an end to racial discrimination. Borrowing the title and format of a 1964 poem by celebrated Afro-Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén, where the poet lists the changes that the revolution has brought for blacks, Hermanos de Causa instead describe the situation for young Afro-Cubans in the contemporary post-Soviet period: “I have a dark and discriminated race/ I have a work day that demands and gives nothing.” Through hip hop, Cuban rappers were reintroducing a lexicon of race and racism that had been abandoned for many years because the revolution had supposedly resolved issues of racism.

It was not always the rap lyrics that created a sense of affinity between U.S. black and Afro-Latinx youth. The Venezuelan gangsta rappers Guerrilla Seca and Vagos y Maleantes were influenced by U.S. rappers like Tupac, Nas and Ludacris. They couldn’t understand the English lyrics, but they said that there was a certain “ flow,” a feeling associated with the music that spoke to them. We can see this echoed in the song “Boca del Lobo” (Mouth of the Wolf) by Vagos y Maleantes. Coming from the poor barrios of Caracas, they felt that the bleakness and despondency of the music echoed the deteriorated social fabric of their lives.

But while global hip hoppers found strong connections to U.S. hip hop, attempts to come together in global alliances revealed the fractures that existed. The pain of racism may have been the bridge that connected the U.S. rappers with those in the diaspora. But that racism took different forms in each context, as the Black August hip hop collective encountered during their trip to Cuba. Some local rappers were bitter about the various rap collaborations done between visiting U.S. rappers and Cuban rappers which tended to make money for the U.S. artists but not the Cubans. Cuban rappers were getting tired of the one way stream of outsiders treating their local scenes as exotic cultures to be packaged for the consumption of western audiences.

The Latinx-American-Cuban connection was somewhat tenuous when subjected to the very real differences of language, culture and history. The black militancy of the U.S. rappers was not comparable to the racial consciousness of Cuban rappers. Black Cuban identity—always expressed within the boundaries of an anti-colonial nationalism—was not equivalent to U.S. blackness, shaped through the ery battles of abolition, desegregation, and civil rights. Cubans didn’t have a civil rights movement that brought a discussion of race out into the open. The black-white dichotomy of American race relations did not exist in Cuba. While in America, even “one drop” of black blood categorized a person as black, Cubans had a much broader spectrum of racial classi cations—from the darker skinned prietos, morenos, and negros to the mixed race pardos and mulatos. The militant stance of the American rappers appealed to the Cubans, particularly with its language of racial justice. But the categories of U.S. racial politics could not be superimposed onto a culture where racial identity was not so clear-cut.

IS IT GLOBAL?

In 2001, Julio Cardenas left Cuba and moved to New York City. He experienced what many rappers after him were to encounter: without professional quali cations or credentials, without family in the states, he was forced to abandon his music and bus tables like many other migrants in the city. Eventually he moved into the area of hip hop theatre, and with a grant from an arts foundation he wrote and acted in a play called “Representa!” with the Chicano poet Paul Flores. The play explores the developing relationship between them in the distinct locales of Havana and New York City. Paul is finishing up college and using his school loans to fund a trip to Cuba. He wants to see the country where his grandmother was born and reconnect to his Cuban roots. The actors stand side by side, Paul in his college dorm planning the trip, and Julio riding a bus in Cuba, both of them speaking aloud their thoughts. Paul wants to see the Cuban hip hop festival. Julio wants to perform in the hip hop festival. Paul wants to dance salsa and drink Cuban rum. Julio wants to go to the Palacio de la Salsa and dance with a beautiful woman. The play explores how Paul, a minority in his own country, has access to certain privileges in Havana that are not available to marginalized youth such as Julio. Walking in the city, Julio is policed and his movements restricted by the authorities. Paul’s discomfort comes from the perception of him as a rich tourist, a positionality he is not used to occupying.

The Latinx-American-Cuban connection seemed to have a better chance of being realized when Cubans and Latinxs could live in each other’s spaces and acknowledge their differences. Even if the global hip hop ‘hood was more a fantasy than actuality, experiences like those of Paul and Julio seem to suggest that the solidarity hip hoppers were looking for could be found in the diaspora. The story of the global spread of hip hop is itself one of movement. A movement of ideas, a movement of commodities, a movement of people. Hip hop is a force defined by rupture and flow. If there is anything that marks this moment, it is as much the motion and mobility that bring us together, as it is the boundaries and borders that divide us.

Winter 2018, Volume XVII, Number 2

Sujatha Fernandes is a professor of political economy and sociology at the University of Sydney. She is the author of several books, including Cuba Represent!, Who Can Stop The Drums? and Close to the Edge: In Search of the Global Hip Hop Generation. Her latest book is Curated Stories: The Uses and Misuses of Storytelling. She tweets at @SujathaTF and her website is: www. sujathafernandes.com

Related Articles

Afro-Latin Americans: Editor’s Letter

My dear friend and photographer Richard Cross (R.I.P.) introduced me to the unexpected world of San Basilio de Palenque in Colombia in 1977. He was then working closely with Colombian anthropologist Nina de Friedemann, and I’d been called upon by Sports Illustrated to…

Witches, Wives, Secretaries and Black Feminists

The issue of gender has been front and center for me, both as a subject of my fieldwork on black politics in Latin America, and how I conducted that research, particularly in how I…

Compañeros En Salud

English + Español

I have lived in non-indigenous rural Chiapas in southern Mexico since 2013, working with Compañeros En Salud (CES)—a Harvard af liated non-profit organization that partnered with…