About the Author

Jimmy J. De La Cruz Castro is an ALB candidate in government at the Harvard Extension School. He is the Harvard chapter president of Turning Point USA, a student organization that promotes freedom. Outside of his academic life, he volunteers at a local school in Cambridge tutoring kids in reading and writing.

Black and Invisible in Peru

In the prologue of Ralph Ellison’s 1952 tour de force Invisible Man, the narrator — an unnamed African-American man — describes his existential condition as he navigates the divided racial lines in mid-century America:

I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgard Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids—and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination—indeed, everything and anything except for me.

Ellison started to work on Invisible Manin 1945 in a barn in Westfield, Vermont, and through the voice of the narrator he attempted to capture the social invisibility of African-Americans as they construct their own racial and ethnic identity in America. Further, Ellison refused to write another protest novel like Richard Wright’s Native Son(1940) or Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin(1852). Instead, he sought to create a “dramatic study in comparative humanity,” in which the narrator “included himself in his indictment of the human condition.”

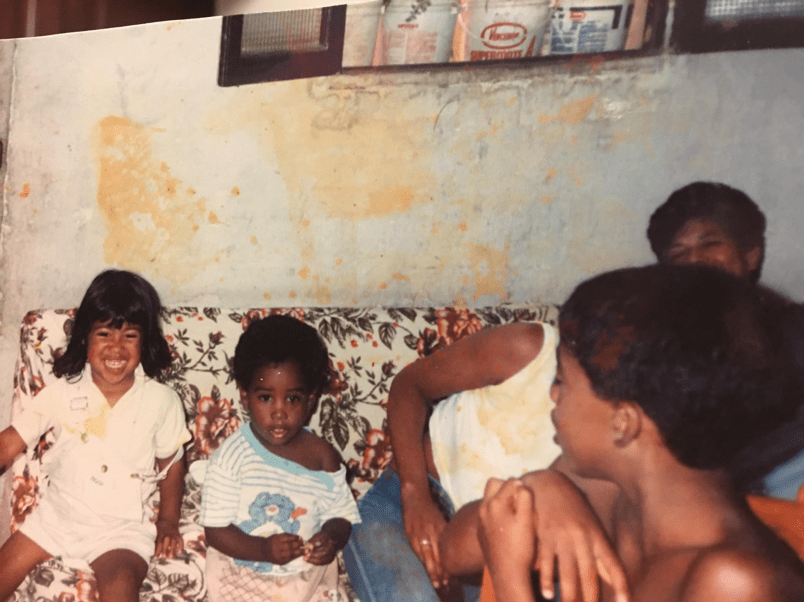

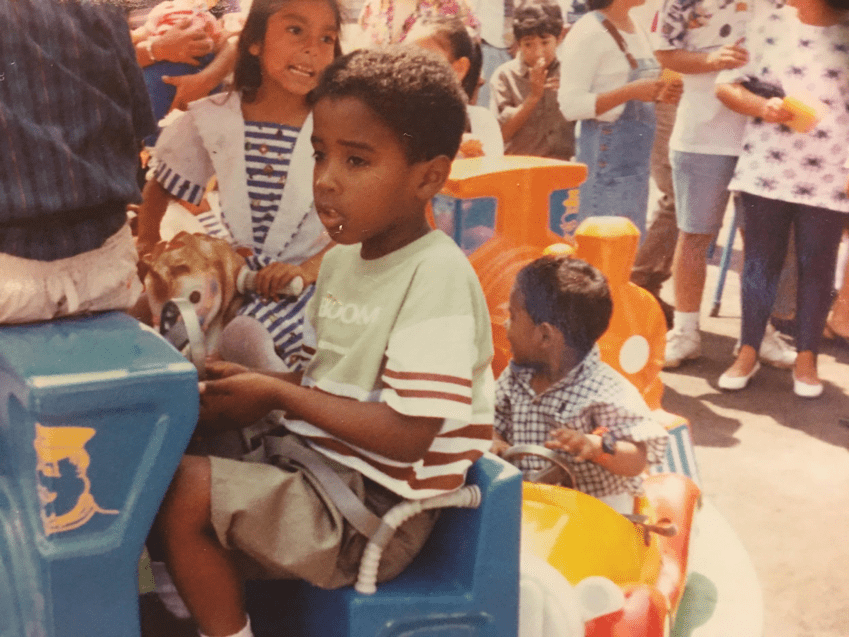

I am not an African-American man forged in the underground of the American experience during a tumultuous time in American history. However, I too have experienced social invisibility. Growing up as an Afro-Peruvian young man in Lima, Peru, I constantly felt invisible. In a country where Afro-Peruvians constitute only three percent of the population, I constantly felt like an outsider or stranger living in my country of birth. Although the neighborhood in the Chorrillos District that I grew up in was racially diverse, the private schools I attended were not. I usually stood out in a crowd of mestizo (Spanish and Indian descendent) and white children, not just for the dark brown hue of my skin, but also for my height. I was rather tall for my age, and usually outperformed my classmates during physical education exercises. In addition to my physical prowess, I was also a high achieving student. I won multiple awards, and often ranked as the top student in my class.

My physical features and my academic performance placed me in a rather unusual position. While I was studious and intellectually curious, the color of my skin both made me stick out like a sore thumb and simultaneously rendered me invisible to the gaze of the mestizo and white individuals around me. To many I was not just Jimmy, but Jimmy “el negrito”, or Jimmy “the black kid”. Similar to the way Ellison’s unnamed narrator describes his interactions with white folks, occasionally I felt like those who approached me only saw a “figment of their imagination,” a stereotyped idea of a young black man. I was looked at, but not seen. Sometimes I felt that I was that young black creature: dangerous, dumb, and good-for-nothing. I was subconsciously constructing a sense of my identity through the eyes of those around me. I internalized these pernicious prejudices constructed to mitigate the inferiority complex of the white and mestizo masses. I was becoming, as James Baldwin once put it, their negro.

Growing up in Lima, I had a limited exposure to the arts, history and culture of Afro-Peruvians. My window into the artistic world of Afro-Peruvian folklore consisted of reading the décimas of the Afro-Peruvian poet Nicomedes Santa Cruz, or listening and dancing to the waltz and festejos of Arturo “Sambo” Cabero or Eva Ayllon during family gatherings. The history of Afro-Peruvians is not taught in public or private schools. If Afro-descendants are mentioned at all is only as an addendum to the broader narrative of the Spanish conquistadors and the subsequent War of Independence from 1811-1826 and the formation of a new Republic in Peru. As I began to explore my identity as an Afro-descendant, I searched in my school’s library and to my surprise I don’t recall ever seeing a book on Afro-Peruvians. To my impressionable mind, I found it strange that there were no black faces in the school texts we were assigned. And when Afro-descendants were mentioned, they only appeared as slaves or house servants.

As I became more aware of the society I lived in, I noticed that Afro-Peruvians lack positive representation in contemporary Peruvain film and media. In a research project I conducted for a class earlier this year, I found that out of the top-ten grossing Peruvian films that were released in 2018 only two of them depict Afro-Peruvians. For example, in Jorge Vilela’s Utopía, a docudrama based on the fire incident that broke out in the exclusive nightclub of the same name and killed 29 people in Peru in 2002, Afro-Peruvians only appear briefly as minor characters in the background. They serve as voiceless props in a film that reinforces a kind of social hierarchy where the affluent and white characters are depicted in prominent roles and mestizos and Afro-Peruvians portray auxiliary and forgettable characters.

Moreover, in both print and visual media Afro-Peruvians are virtually absent, and if they are represented at all they are often portrayed in a negative light. It is not uncommon for Peruvians to pick up a diario chicha (tabloid newspaper) and encounter stories accompanied by crude images of Afro-Peruvians described in belittling and disparranging tones. Afro-Peruvian men especially are often depicted as thugs and criminals or in some cases as beasts full of aggression. In Peruvian media, minstrelsy is the main form in which racial stereotypes are reinforced. For example, in a popular show called El Wassap de JB, comedic actor Jorge Benavides plays a blackface character called “El Negro Mama.” He is depicted as a dumb and inept delinquent whose motto is “Seré negrito, pero tengo mi cerebrito” (I may be a little blackie, but I have my little brain). In other instances, Benavides dresses up in blackface featuring ridiculously big lips and wears urban and gaudy clothes to imitate Peruvian soccer players Jefferson Farfán and Luis Advincula. While there have been efforts by Afro-Peruvian advocacy groups like LUNDU to remove characters like “El Negro Mama” from Peruvian television that reinforce racist stereotypes, Benavides’ modern minstrelsy show is still watched by thousands on Sunday nights.

It wasn’t until I arrived in the United States in 2003 that I began to understand my identity as an Afro-descendant. I furiously read the history of African-Americans, from their arrival in Jamestown, Virginia in 1619 to their participation in the Revolutionary and Civil war to the abolition movement and the Harlem Renaissance and Civil Rights movement. I read slave narratives, including Frederick Douglass’ accounts of his life as a slave in a plantation in Maryland and later as a leading abolitionist, and Harriet Tubman’s incredibly brave attempts in leading slaves to the north to freedom in the Underground Railroad. I later studied Dr. Martin King Jr. in middle school (teachers at my school were very careful not to introduce any speeches by Malcolm X), his Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the movement that culminated with his “I Have a Dream” speech at the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. In high school, I picked up Booker T. Washington’s Up From Slavery, and W. E. B. DuBois’s The Souls of Black Folks, both books represented the divergent intellectual schools of black thought in the early 20th century. Moreover, works like Richard Wright’s Native Son, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, and Langston Hughes’s poems and memoirs deepened my understanding of the black experience in America. However, the writer that provided the intellectual stimulus that I was looking for was the economist and social theorist Thomas Sowell. His oeuvre—which includes an impressive collection of books including The Quest for Cosmic Justice, A Conflict of Visions, and Black Rednecks and While Liberals—illuminates the historical and philosophical underpinnings that informs our understanding of political differences and group outcomes. Reading his work profoundly changed my understanding of history, economics, race, society, and culture. And made me understand that it doesn’t matter where you come from, but where you end up.

Although Peru has developed over the past two decades to become one of the best performing economies in South America, it has stagnated in terms of race relations and its failure to address the problems that particularly affect its Afro-descendant population. According to a 2013 report by the UN Development Programme (UNDP), Afro-Peruvians are discriminated against in the labor market, in many cases due to low levels of education. Only six percent of Afro-Peruvians attend university, as opposed to the twelve percent national average. Moreover, Afro-Preuvians continue to face prejudices in society. Their depictions in film and media are often informed by racial stereotypes and ignorance. As I’m considering attending graduate school in the near future and pursue a degree in public policy, I think it would be remiss of me not to go back to Peru after I graduate from Harvard, and address some of these issues that affect my community. I believe a brighter future is ahead for Peru and my people.

More Student Views

Beyond Presence: Building Kichwa Community at Harvard

I recently had the pleasure of reuniting with Américo Mendoza-Mori, current assistant professor at St Olaf’s College, at my current institution and alma mater, the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Professor Mendoza-Mori, who was invited to Madison by the university’s Latin American, Caribbean, and Iberian Studies Program, shared how Indigenous languages and knowledges can reshape the ways universities teach, research and engage with communities, both local and abroad.

Of Salamanders and Spirits

I probably could’ve chosen a better day to visit the CIIDIR-IPN for the first time. It was the last week of September and the city had come to a full stop. Citizens barricaded the streets with tarps and plastic chairs, and protest banners covered the walls of the Edificio de Gobierno del Estado de Oaxaca, all demanding fair wages for the state’s educators. It was my first (but certainly not my last) encounter with the fierce political activism that Oaxaca is known for.

Public Universities in Peru

Visits to two public universities in Peru over the last two summers helped deepen my understanding of the system and explore some ideas for my own research. The first summer, I began visiting the National University of San Marcos (UNMSM) to learn about historical admissions processes and search for lists of applicants and admitted students. I wanted to identify those students and follow their educational, professional and political trajectories at one of the country’s most important universities. In the summer of 2025, I once again visited UNMSM in Lima and traveled to Cusco to visit the National University of San Antonio Abad del Cusco (UNSAAC). This time, I conducted interviews with professors and student representatives to learn about their experiences and perspectives on higher-education policies such as faculty salary reforms and the processes for the hiring and promotion of professors.