Bodies That Sing

Forró Music in a Traditional Setting

A couple dances forró; such scenes take place in rio de Janeiro, são paulo, new york City…and even new Jersey. Photo by Megwen Loveless

We arrive at a doorway hidden in the shadow of a 24-hour convenience store, and dig crumpled bills from our pockets, surrendering them to the barrel-chested man in a tight black tank top. The scene is a reminder of what an inspired idea it was to leave my purse at home; the plan is to dance all night long. Having paid, we step carefully down a winding staircase and perch on tipsy-toed stools at the bar with a great view of the dance floor.

The ceiling is low and the only lights are strategically placed orange, red, yellow and green bulbs. The band begins to gather on stage, gesticulating to one another in the semi-darkness. Once set-up is complete, lights flood the stage and with a shout the band launches into their first set. The room is transformed as people surge onto the dance floor. Sounds of live accordion and percussion bounce off the walls. Forró music pumps energy into the bodies of the dancers, and they grind, twist, turn, hop and cling to one another, creating a mural of gyrating bodies whose sultry aerobics scream: festa!

Forró captured my attention while living in the northeast of Brazil in the late 1990s and has since taken me to dancing joints in São Paulo, Rio, New York and even New Jersey. Described as “a mixture of ska with polka in overdrive” by musician and record-producer David Byrne, forró pé-de-serra (“foothill” music), traditional forró is typically performed by a three-piece band consisting of accordion, triangle and zabumba (a double-headed-drum). In New York, the few bands that regularly perform have added more modern instruments (bass, drum sets) but continue to play from the authentic forró repertoire of songs. Interestingly, I find that most forró music played in New York is relatively typical of all of Brazil, but a close look at the dancers reveals pronounced regional affinities, alliances, and discrepancies expressed through dance style and choreography.

My research examines the different styles of dance that develop as forró stretches across provincial and national borders. The previous paragraph, taken from my field notes after a long night of dancing in Manhattan, demonstrates what an international phenomenon forró has become. It sets the stage for the story of how a relatively unknown folkloric music from the Brazilian rural northeast has come to play a key role in how Brazilians articulate their identity as migrants in foreign settings.

This folk music from Brazil’s nordeste region has become an ideological tool for an increasingly cosmopolitan and globalized Brazil. It helps emigrants venture into the global economy while maintaining a tight knit sense of place and home. I am particularly interested in how Brazilians use forró as a marker of identity: while forró music symbolizes the nation as a whole, Brazilians from various regions dance to it differently. Thus, forró dance styles allow Brazilians to feel a sense of national pride and belonging while simultaneously expressing regionalism and differentiating their provincial identities. Regional distinctiveness can be read through bodily expression on the dance floor, creating a lexicon through which Brazilians position themselves—and their local identities—in a transnational setting.

While framed as traditional music tied to a rural and bucolic past, forró has been dynamically recreated over time, developing into several genres in both rural and urban settings. My research focuses on the more traditional and rural styles because of my interest in how Brazilians imagine their own identity; something about forró pé-de-serra smacks of the “authentic Brazil” in a way other genres do not.

HISTORY OF FORRÓ

From its conception, forró has been tied to migration. It was not only created from, but continues to be consumed, because of an ever-growing cycle of Brazilian emigration. Before we look at this larger issue of immigration, however, I’ll introduce the traveler who first “brought the triangle, gonguê (cowbell) and zabumba” (as he sings in a 1950s hit) to the entire nation.

The story of forró begins with Luiz Gonzaga, known today throughout Brazil as the undisputed pioneer of the genre and one of the country’s most iconic symbols of nordestinidade, or northeastern identity. A gregarious son of an accordion player, Gonzaga’s ambitious wanderlust led him from his birthplace in rural Pernambuco to a budding forró career in the capital of Rio de Janeiro in the 1940s. His popularity, made possible by the burgeoning importance of radio, arose from his introduction of northeastern rhythms and melodies into a southern Brazilian musical culture then dominated by waltzes, mazurkas, foxtrots, schottishes and tangos. Gonzaga’s first major success was the 1941 hit Vire e Mexe (literally “Turn Around and Boogey”), an instrumental accordion piece that immediately caught the nation’s interest because of its new sound, framed by radio producers and Gonzaga himself as traditional flavor from the backlands of the northeast.

Forró has always been primarily a dancing music. It’s quite impossible to listen to it without twitching toes and feet in time, swaying hips back and forth between the measures, clapping out the hard clave rhythm that the drum teasingly withholds underneath its own beat.

Even its etymology—though hotly debated—refers to dance. The version most travelers will hear is that the word really originated from a clever Brazilian pronunciation of English. According to this story, a British railroad company laying tracks across the nordeste sponsored regular social dances as a “release mechanism” for underpaid nordestino workers; the dances had free admission and were open “for all.” Another version, preferred by ethnomusicologists, argues that the word derives from the word forrobodó (possibly of African Bantu origin), which refers to a place in which a community dance occurs. Throughout the high points of Gonzaga’s career, forró’s delicious fusion of music and dance was promoted. Every few years, the famed nordestino would invent a new style of dance to go with the release of his latest hit, reinforcing the connection between music and dance, and between the northeast and south.

BRAZILIAN HISTORY AND IMMIGRATION

Since its independence in 1822, Brazil has struggled to create a national identity to unite its diverse and dispersed regions and ethnic communities. The nation’s diversity (or fragmentation, depending on your perspective) is evident in Brazil’s curious tendency to refer to itself in the plural: “os Brasis.” Successful political regimes over the past two centuries have constructed an official ideology that often hinges on cultural forms (such as samba) to substantiate claims of national cohesion. Still, Brazil has remained very much divided across a north-south axis. The north is associated with the dried-up colonial sugar-cane economy, while the south represents the industrialized cities that have become the financial powerhouses of the nation. Worsening the divide were cyclical droughts that plagued the area west of the sugar-cane plantations, triggering huge exoduses of rural subsistence farmers pushed off their land. During the 1960s and 1970s, hundreds of thousands of migrants fled to the big urban centers along the coast or in the south.

Part of Gonzaga’s appeal as a performer was the fact that he was a “country bumpkin” who had “made it” in the cosmopolitan south—a success which spoke to to the thousands of nordestinos economically exiled in the southern cities where rapid industrialization demanded low-wage workers. For these migrant nordestinos, forró music became a way of accessing their native land through saudade (“nostalgic longing”). The lyrics of Gonzaga’s canonical tunes are imbued with the struggle of nordestinos and their hostile yet beloved land, thus creating a way to be emotionally present while physically absent from home.

At the same time as these impoverished nordestinos were scraping a living working as servants in affluent homes of the south, changes brought on by the growing and increasingly globalized Brazilian economy began to change the cultural orientation of the middle and upper classes that employed them. The perception that foreign conglomerates dominate the Brazilian economy has shifted the sense of national culture and national identity. Even as they participate freely in transnational politics and exchange, the “haves” of the industrialized south have come to covet what the “have-nots” of the northeast have in abundance: traditional values and lifestyles. Thus the middle- and upper-class southerners have begun to look to forró as a representation of Brazil’s rural and bucolic past, an imagined place and time untouched by modernity that somehow better reflects a truly authentic Brazilian psychology.

REGIONALLY INFLECTED FORRÓ

In the early 1990s, forró hit the dance clubs of São Paulo and Rio, and a whole new segment of the population began to swivel and slide on the dance floor. They called their style universitário (“university”) because of the many students, intellectuals and urban culture brokers who hopped from club to club. Interestingly, forró universitário and forró pé-de-serra do not sound very different. However, they look quite different. Northeasterners and southerners have different experiences while listening and dancing to this music, which can be seen in their variations in body movement.

Metro New York, along with Boston and Miami, has been a node of Brazilian immigration since the late 1980s. Nova Iorque is my home—as well as home to perhaps the most diverse population of Brazilians in the U.S. North and south tend to blend more here than anywhere in Brazil. The dance floor is no exception. I return to my field notes from that night out dancing in Alphabet City.

Couples dancing forró generally followed the style of the male lead. Pernambuco: tight, tight dancing, with thighs intertwined and nothing to embellish the grinding. São Paulo: almost sporty, with casual turns and sexy pauses and clearly demarcated shoulder space. Rio: pretty twirls that remind me of latticework on a balcony in Lapa. As the female dancers switched partners I watched as their style changed: some added or subtracted spins, slid closer to or further from their partner, or threw in pauses or dips. The men stuck to their own style, performing signature moves that reflected more of a regional tendency than individual style.

Forró is a dance in which a national rhythm can find its voice in a variety of bodies. It is a performance in which regional accents play off one another. Ultimately, it is a genre in which diverse styles speak the same language, albeit with lilting cadences of difference. I’ve found that while forró music and lyrics can tell me about Brazilian national identity, forró dance elucidates Brazil’s distinctive regional identities. Taken together, forró performance can shed light on both the unity and diversity of Brazilian identity. It may be, in fact, the perfect medium for communication across the cultural, social, and regional separations that both divide and unify Brazil.

Megwen Loveless is a PhD Candidate in Social Anthropology at Harvard University. The above essay is an excerpt from her dissertation on forró music and dance, currently in progress. Megwen lives in New Jersey, where she teaches Portuguese at Princeton University.

Related Articles

Review of Going Local: Decentralization, Democratization, and the Promise of Good Governance

This methodologically rigorous and carefully crafted book is an exercise in good scholarship. Like its subject of good governance, it is an embodiment of leadership, performance, accountability and a commitment to constructive policymaking. Merilee Grindl has already made her reputation as a painstaking scholar of governance, bureaucracy and policymaking in Latin America and across the developing world, but Going Local …

Making A Difference: Connecting the Diaspora with Caribbean NGOs

E.One.Caribbean, an initiative based at LASPAU, seeks to engage the Caribbean diaspora in reinvigorating their home countries by providing financial, volunteer, and capacity-building resources to NGOs whose work addresses the social problems that threaten long-term economic and cultural viability. The program was developed by Norris Prevost—a longtime member of the Parliament of Dominica and recent graduate of the …

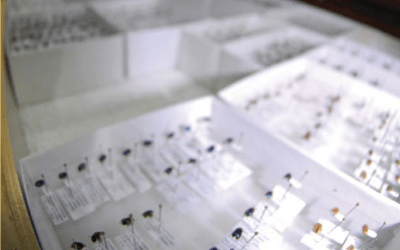

Making A Difference: Insects and Internet: Saving a National Treasure in Hispaniola

On July 11, 2007, the oldest university in the Americas, the Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo (UASD), marked the first anniversary of the entry of its natural history collections into the digital global community. These priceless collections record the changing abundances of species over the 20th century, including many species new to science and some that are perhaps already extinct. The collections of insects alone are …