Bolivia’s Mother Earth Laws

Is the Ecocentric Legislation Misleading?

I distinctly remember sitting in the audience of a well-known animal law conference in the United States a few years ago. The panelists presented some less-known legislation around the world that could be deemed as promising and beneficial to furthering the animal rights, or at least the animal welfare, agenda. One of the countries they mentioned was Bolivia, specifically its Mother Earth law, which they praised as an example of progressive legislation, full of substantial provisions which could protect animals.

Courtesy of Rosalie Parker Loewen.

They compared it to the constitution of Ecuador and deemed the Bolivian law could be used as a possible basis to grant nature some kind of personhood to defend her interests, as had happened in specific cases around the world (for example, the Whanganui River case in New Zealand).

When this came up, instead of feeling proud as a Bolivian in the audience, I felt disheartened, annoyed and concerned. Their point of view to me not only seemed far from the truth, or at the very least naive, but also very dangerous, since the reality of this law’s conception and how it had been applied until then was abysmally different. During the question period, I grabbed the microphone and expressed my opinion hoping for everyone to hear it and take some of the information I provided into account. However, I still felt uneasy about it and I decided that voicing my opinion in that scenario was not enough. I should be working towards stopping the spread of misinformation. Since that day, I have been trying to spread the word. This article is one of the rare chances to do so.

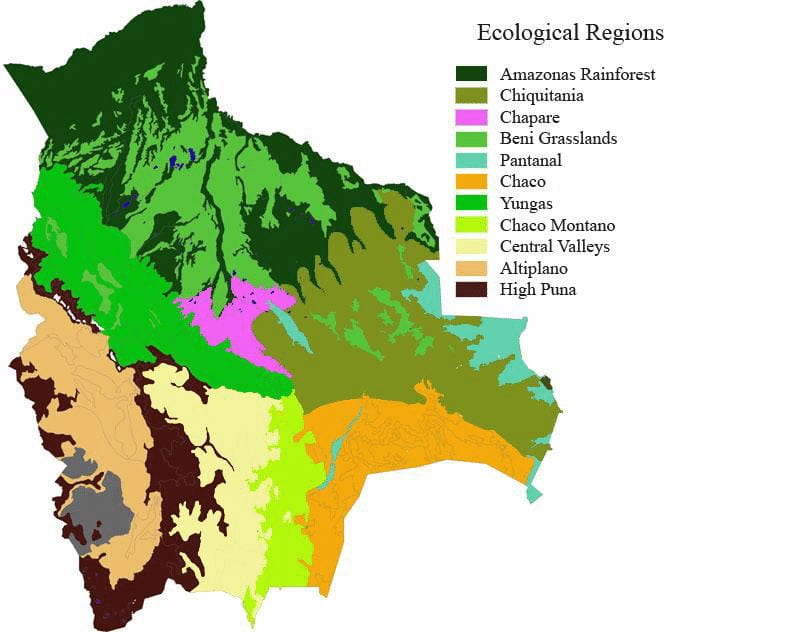

Bolivia is a landlocked country in the middle of South America that not many people know much about. Although our population is not that significant compared to other countries (around 12 million according to the World Bank Group) we have a vast territory which includes a wide rage of ecosystems, where the diversity of animal and plant life is among the greatest in the world (American Museum of Natural History’s Center for Biodiversity and Conservation and Bolivian partners, Exploring Bolivia’s Biodiversity).

Bolivia’s ecological regions. Source: Rivera (1992) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234757438_Poverty_Reduction_at_Risk_in_Bolivia_An_Assessment_of_the_Impacts_of_Climate_Change_on_Poverty_Alleviation_Activities

Bolivia’s 2009 Constitution recognizes the importance of protecting nature. However, unlike the Ecuadorian constitution, it does not establish any constitutional rights of nature. The rights of nature, Pachamama or Mother Earth in the Bolivian indigenous tradition, and its protection are set out in two statutes: (a) Law Nº 071 of December 21, 2010 Mother Earth Rights Law (Ley de Derechos de la Madre Tierra)—the Mother Earth Law—, which establishes specific rights to which Mother Earth is entitled; and (b) Law Nº 300 of October 15, 2012, Framework Law of Mother Earth and Integral Development for Living Well (Ley Marco de la Madre Tierra y Desarrollo Integral para Vivir Bien)—Mother Earth Framework Law—, which seeks to put into operation the rights of Mother Earth set out in the former law, in the context of Integral Development (Desarrollo Integral) for Living Well (Vivir Bien).

Although it is true that these laws provide some definitions and provisions that could be useful for protecting Mother Earth and all her members, including animals (Pachamama is defined as the dynamic living system comprised by the indivisible community of all life systems and the interrelated, interdependent and complementary living beings, that share a common destiny. Mother Earth is considered sacred; it nurtures and it is the home that contains, sustains and reproduces all living beings, ecosystems, biodiversity, organic societies and the individuals that form it), there are significant problems with these laws from the moment they were passed. Discrepancies exist between them, the constitution and other laws and regulations, opposing government political and economic interests, language ambiguity, underlying contradictions and enforceability problems which I consider deem them inapplicable in reality.

Mother Earth Law and Mother Earth Framework Law emerged from the new constitution’s Indigenous-derived concept of Living Well, which entails living in complementarity, harmony and equilibrium with Mother Earth. Both laws were supposed to be the result of a negotiation process between the government and the “Unity Pact,” a coalition of Bolivian peasant-Indigenous organizations of Bolivia. After nine months and many meetings, both parties agreed on the final version of a draft law. This draft law distinctively kept an ecocentric orientation since it established that whenever there was a conflict of interests, the protection of Mother Earth should prevail. It was also established that the Bolivian economy had to shift away from fossil fuels and focus on new friendlier-to-earth sources. This draft law, although already agreed upon, ended up not being approved, nor adopted, by the government, since it went against many of their future extractive and commercial projects.

Instead, the government approved these two laws which were prepared mostly by pro-government assembly members, government officials and a few pro-government Indigenous organizations that broke away from the “Unity Pact.” Thus, the resulting laws were considered a watered-down version of the draft law that had been agreed upon. As a result, the adoption of both these laws was opposed by the members of the “Unity Pact,” who felt alienated and deceived by the government, and decided to withdraw from the legislative process, arguing irreconcilable differences regarding the content of the laws. One of the biggest Indigenous organizations, CONAMAQ, and the Indigenous legislators, denounced these laws as a violation of the Indigenous people’s rights and a strategy of the government to be able to continue with its extractive plan, allowing so-called development projects through protected Indigenous territories.

Equally concerning is the fact that these laws contradict some constitutional provisions and other laws and regulations in Bolivia. Although the new Bolivian constitution recognizes the protection of nature to be of great importance, it also includes several anthropocentric provisions, which go against against Mother Earth’s interests. Articles 9, 306 and 355, for example, establish that the government must place the highest value on human beings and one of their main priorities is to promote the use and industrialization of natural resources and activities such as the exploration, exploitation, refining, industrialization, transport and commercialization of non-renewable natural resources. These activities are constitutionally considered matters of state necessity and public utility.

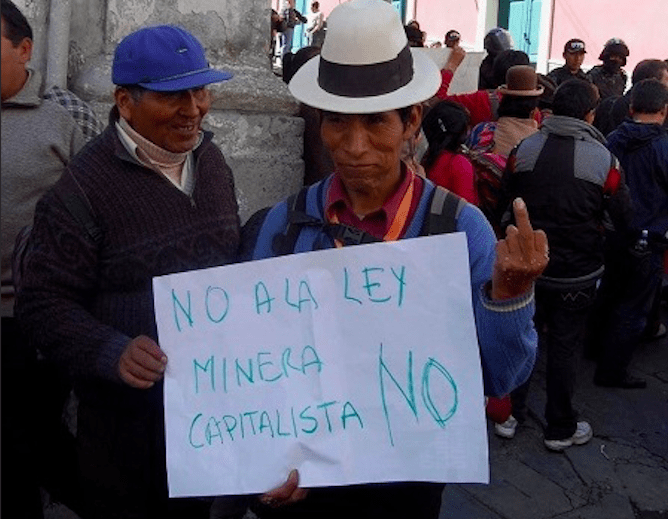

As for other contradicting laws, in May 2014, the government enacted a new mining and metallurgy law, which limits the protection of Mother Earth by keeping pre-existing mining rights concessions and contracts, even when they go against environmental interests, and it allows for mining on protected natural areas (Law Nº 535). Additionally, and as a consequence of these mining concessions, the mining industry is allowed to use the country’s water resources without any additional license or regulatory control. In general, and since both Mother Earth laws were passed, the Bolivian government has eased up on environmental standards to allow for non-renewable resource exploration and exploitation, under the disguise of Integral Development, regardless of its impact on Mother Earth. One example of the consequences of the over-exploitation of water resources in the country and the inefficacy of the Mother Earth laws to fulfill their purpose can be found in Oruro, where mining is considered to be the primary cause for the disappearance of Lake Poopo, which once was Bolivia’s second-largest lake and home to more than 200 species of animals and plants (NASA, Earth Observatory, Bolivia’s Lake Poopo Disappears).

CONAMAQ members protest against mining laws. Source: Territorios en Resistencia https://towardfreedom.org/story/archives/environment/bolivia-s-conamaq-indigenous-movement-we-will-not-sell-ourselves-to-any-government-or-political-party/

Some examples of other regulations that go against Mother Earth’s protection and allow for extractive activities with great environmental consequences, even in protected natural parks, are: Supreme Decree Nº 2298 (makes the procedure for obtaining the consent of Indigenous native peasant nations and people for hydrocarbon sector activities in their territories even more lax), Supreme Decree Nº 2366 (allows for the exploration and exploitation of fossil fuels in all the Bolivian territory and explicitly in protected areas), Supreme Decree Nº 2400 (lowers environmental standards for the hydrocarbon sector) and Supreme Decree Nº 2992 (expands on the list of permitted hydrocarbon exploration projects, works and activities).

It is also important to take into account that there are deeply vested corporate-driven neoliberal and political economic interests in Bolivia. Against these interests, the Mother Earth laws have done very little, if anything, to effectively protect nature, specially when we take into account that one of the government’s priorities is development, in a country where poverty is widespread and natural-resource extraction activities are usually the easiest and most lucrative way to ensure the government enough economic resources to advance their political agenda. It is also important to take into account that the greatest violations to environmental laws and regulations are perpetrated by the government itself. Since the passing of these laws, the Bolivian government has pushed for numerous projects which involve the invasion of protected areas and the violation of Indigenous people rights.

In 2011, the government started the construction of a highway across the Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory—TIPNIS— which is a protected area and native community land, with an extension of 1,372,180 hectares. Its territory includes four major ecosystems: flooded savannas of the Moxos plain, sub-Andean Amazonian forest, pre-Andean Amazonian forest and Bolivian-Peruvian Yungas. The area is particularly rich in flora and fauna, congregating around 700 plant species, 218 mammal species, 992 bird species, 157 amphibian species, 131 reptile species and an indeterminate number of unidentified species (ParksWatch, Bolivia, Parque Nacional y Territorio Indígena Isiboro Secure). Although the Indigenous people and environmental activists organized various protests to oppose the construction of this highway, in August of 2017 the government enacted a new law specifically allowing for the highway’s construction and reversing the ‘untouchable’ status of this territory. The Mother Earth laws were not even taken into account. The destiny of more than twenty indigenous populations and of all the park’s animals and plants is currently uncertain, with very little hope for success in protecting this national park and all its inhabitants.

Additionally, the Mother Earth laws have fundamental contradictions within them, between the Indigenous ecocentric vision and the neoliberal development government plan. Mother Earth Framework Law introduces the Integral Development concept as a specific type of modern development, but defines it ambiguously and still links development with the exploitation of natural resources. Environmentally harmful activities, such as mining and oil extraction, are legitimized in the law in order to ensure the country’s development. The law is neither specific nor concrete, and the possibilities for tangible applications are limited.

Moreover, the enforcement of this law is very unclear. The law mentions an administrative and a jurisdictional protection. For the administrative protection the government must create the specific regulation and technical-administrative department to enforce it, but to this date no specific department has been created. For the jurisdictional protection the ordinary courts and a couple of specific courts are in charge of enforcing the law. However, due to the quantity of cases the ordinary courts must handle, it is very unlikely that any case would be pursued there. These laws also provide for the creation of the Mother Earth Ombudsman (Defensoría de la Madre Tierra), which still does not exist to this date (12 years after the first law came into force).

Lastly, to this date there has not been any significant litigation in the country based on these laws, and it is very unlikely that any case filed to protect Mother Earth by an individual would be successful, especially when we take into account that the greatest violations to the laws come from the government, which basically manages the judiciary nowadays.

The Mother Earth laws sadly have become statutory devices to legalize the exploitation of natural resources in Bolivia, instead of protecting Mother Earth. By promoting extractive activities in order to achieve the Living Well objective, on one side, and the defense of Mother Earth, on the other, these laws end up being highly contradictory, making environmental protection a secondary objective, which is contingent to the government’s prevailing economic interests. In reality these laws did not translate into any improvement in environmental policies in Bolivia and they only served to bolster the deceptive image of the Bolivian government as an international pioneer in environmental protection.

It is not enough to pass laws with abstract Indigenous visions and apparent non-capitalistic concepts if they are not coupled with concrete practices, real actions and enforceability mechanisms. These laws will never be effective if there are no new public policies to change the current non-sustainable production pattern, shifting away from extractive practices that go against Mother Earth’s survival. As long as there is this fundamental dissonance between these laws’ provisions, other legal provisions and specially the Bolivian government’s practices, there is little hope for any improvements in future environmental and animal protection efforts based on there Mother Earth Laws.

Until all these changes happen, every time anyone mentions these laws, I will keep grabbing the microphone, or my computer like in this case, to prevent people from romanticizing them and giving them an undeserved ecocentric appraisal.

Lorna Sara Muñoz Prudencio (BS, MCom, JD, LLM) is an attorney and bachelor of science in cynology. She received a Masters Degree in Commerce and International Relations and an LL.M. Degree in Animal Law. She is currently working independently, focusing on her work as a non human animal rights activist, a grassroots lobbyist, a dog rescuer and overseeing various cases related to animal law in her country.

Editor’s Letter – Animals

Editor's LetterANIMALS! From the rainforests of Brazil to the crowded streets of Mexico City, animals are integral to life in Latin America and the Caribbean. During the height of the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns, people throughout the region turned to pets for...

Where the Wild Things Aren’t Species Loss and Capitalisms in Latin America Since 1800

Five mass extinction events and several smaller crises have taken place throughout the 600 million years that complex life has existed on earth.

A Review of Memory Art in the Contemporary World: Confronting Violence in the Global South by Andreas Huyssen

I live in a country where the past is part of the present. Not only because films such as “Argentina 1985,” now nominated for an Oscar for best foreign film, recall the trial of the military juntas…