Roque Dalton

The Magnificent Wound that Never Heals

The work of Roque Dalton (1935-1975) is one of El Salvador’s national treasures. Dalton garnered the admiration of many distinguished writers and intellectuals, ranging from Julio Cortázar to Régis Debray, from Mario Benedetti to Elena Poniatowska. In a region whose writers have had difficulty not only penetrating the circuitry of the so-called First World’s cultural establishment but also that of much of Latin America, this is quite unusual. He achieved this status not only through his brilliant command of the Spanish language and sparklingly mischievous (and corrosive) sense of humor, but also through his unrelenting commitment to revolutionary change.

That commitment is one reason why the insertion of his work within today’s cultural and political atmosphere becomes problematic on many levels: it can appear “archaic,” “déphasé,” in a moment of triumphant capitalism conjoined with postmodern skepticism. Dalton was always completely upfront about his ideological convictions (including his commitment to armed struggle), and while much of his poetry (the genre in which he flourished most) centers on the range of themes found throughout the ages such as love, solitude and death, one is always encountering unequivocal signs of his deep political engagement. This is why I have consistently insisted that Dalton was a “revolutionary who also wrote” rather than a “writer who was also engaged in revolution.”

As many readers will know, Dalton’s involvement in bringing revolution to his impoverished native land cost him his life. And yes, he died not at the hands of the military dictatorship ruling the country at the time, but at those of “comrades” of the Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo (ERP), the revolutionary organization he joined after his clandestine return from Cuba to El Salvador at the end of 1973. Dalton became caught up in internecine squabbling with ERP leaders on issues of strategy, and in May 1975 he and a fellow member of the organization were “arrested,” put on “trial” and subsequently “executed.” His enemies accused Dalton of being a CIA agent—an accusation that was subsequently retracted when the ERP leadership admitted that his “execution” was a mistake.

The exact circumstances surrounding Dalton’s murder have never been definitively clarified, nor have his remains ever been recovered. Several of the individuals directly involved in the events are still alive, including Joaquín Villalobos (the supreme commander of the ERP forces during El Salvador’s civil war that lasted from 1980 to 1992) and Jorge Meléndez (his second-in-command). The Dalton family—including his widow (Aída Cañas) and his two surviving sons (Juan José and Jorge)—have insisted over the years that those responsible for his death should be tried for murder. They also have demanded that his burial place be revealed.

After a failed attempt to enter electoral politics after the signing of the 1992 peace accord, Villalobos subsequently swerved sharply to the right, studied at Oxford (where he still lives), and became a consultant on “conflict resolution” for governments facing armed insurgencies such as Colombia, Mexico and Sri Lanka. He resolutely refuses to discuss the Dalton affair, though at one point admitted in an interview that the ERP leadership’s acts constituted an “error de juventud” (a “youthful error”). Villalobos has become a complete bête noire for his former comrades in the Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN) and is unlikely ever to reveal exactly what happened.

A very different path was followed by Jorge Meléndez. He remained in El Salvador after the war, became active in politics and still heads a small party allied with the FMLN. After the 2009 FMLN electoral victory, he was named head of Protección Civil, the governmental agency that responds to natural disasters. Needless to say, this was a source of outrage for the Dalton family, which nevertheless has remained steadfastly committed to the FMLN up to the present day. (Now a journalist and director of Contrapunto, Juan José was an FMLN combatant and was captured and tortured by the Salvadoran army.) During the government of Mauricio Funes the family initiated legal actions to prosecute both Villalobos and Meléndez, but these did not fare well given the general amnesty that was declared as part of the peace accords. The Dalton family persisted in its efforts, requesting that the FMLN government at least dismiss Meléndez from his prominent position. It never happened.

The family renewed its efforts after the electoral victory of the FMLN in 2014, and the assuming of the Presidency on the part of Salvador Sánchez Cerén, a key commander of the FMLN forces during the war. Its hopes were crushed when Meléndez was named, once again, head of Protección Civil.

Meléndez has consistently refused to reveal what his precise role was in Dalton’s “execution,” largely making the argument that this sort of thing is to be expected, more or less, in the type of conflict that was emerging in the early seventies, and also invoking the exculpatory notion that our author was “tried” by a revolutionary military tribunal and found guilty on the basis of the “evidence” then available.

For someone who studies and teaches Dalton (in my own case, for more than thirty years now), this lingering state of affairs presents an array of vexing obstacles. Whenever I tell people that I am writing a book about Dalton, the first thing that comes out of their mouth is: “So who exactly killed him?” If the person is coming from the right, there is always a grimly self-congratulatory air that suffuses the way the question is posed (“You see! The left kills its own!”). If the person belongs to the left, the question is inspired by honest curiosity, tinged with immense sadness and almost a kind of guilt (“How could our comrades have done something like that?”).

Mixed with the never-ending “Whodunit,” we have the near legendary air that surrounds Dalton, one that often threatens to turn him into a “pop celebrity” of sorts. Dalton developed a (well-earned) reputation as a drinker of epic capacity as well as an incorrigible womanizer. This has led many to fashion him as a scintillating bohemian writer and “dreamer” who stumbled, essentially by accident, into the revolutionary politics that got him killed. With this image as a point of departure, many scholars have striven to craft a “Roque-for-the-academy”—that is, a Roque Dalton whose poetic brilliance, fueled by his flamboyant life-style, justifies jettisoning, for the most part, any evidence of his hard-line Marxism-Leninism. This, in turn, facilitates circulation of his work in seminars, academic journals and other venues.

The “Dalton phenomenon” can only be fully understood if one looks at the entirety of his production: all of his poetry (including Un libro rojo para Lenin [A Red Book for Lenin]), not just the more lyrical variety, his historical works and theoretical writings about revolutionary struggle, and yes, his very “nuts-and-bolts” texts on guerrilla warfare. Quite frankly, I do not think that there is a comparable figure anywhere in Latin America, nor perhaps in the rest of the world. Studying all of his writings is really the only way to do justice to the rich complexity of his work and his life.

And when I say this, I do so not as a critic interested in presenting “new, improved” Roque-for-the-academy; rather, as someone who believes that the problems of Latin America, and much of the rest of the world, can only be solved from the left. And since the collapse of existing socialism in the early 90s, the left has been searching for a new language, for new ways to mobilize the people who need to be mobilized. I am convinced that Dalton has something to say to us at this moment in history, especially as the left makes inroads in much of Latin America (albeit with ups-and-downs). He believed that armed struggle was the only way out of the never-ending nightmare of Latin American history, particularly in the wake of the overthrow of democratically elected Socialist President Salvador Allende in Chile. However, he was by no means tied to armed struggle as universal “cure-all.” The very vibrancy of his thought, which is connected to that of his poetry, would have him thinking of new paths forward, particularly at a moment in Salvadoran history when a former FMLN guerrilla commander is the country’s president.

It speaks well of those who planned the presidential inauguration on June 1, 2014, that they included Dalton in the exhibition of photos of Salvadoran heroes and martyrs—such as Farabundo Martí and Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero— held up by “living statues” along the walkway leading to the auditorium. And when Sánchez Cerén invoked Dalton in part of his speech, it sparked one of the loudest and most sustained applauses of the entire proceedings. It is clear that the FMLN wants to maintain Dalton as part of its pantheon of heroes, particularly given his continuing appeal to young Salvadorans. And it cannot be anything but galling to its leadership and militants to witness how the Dalton case continues to be used as a stick with which to hit them. The ongoing “mystery,” and the fact that one of its protagonists continues to occupy an important government post, still provides fodder for the Salvadoran right in its unceasing battle to thwart the FMLN at every turn.

It is worth remembering that it was under ARENA governments of the mid-nineties that Dalton was officially brought to the center stage of Salvadoran culture. Among other things, a governmental publishing organ was responsible for the appearance of the first major anthology of Dalton’s poetry in the country after the ban in effect during the war. Under ARENA, a postage stamp dedicated to Dalton was issued; he was bestowed a posthumous honor that essentially recognized him as the national poet of El Salvador. Had the right caught him when he was still alive, they would have killed him (as they were very close to doing on a number of occasions). But once the the left itself did them the favor of getting rid of Dalton, he provided them substantial ammunition for the electoral dynamics of the post-war period.

Dalton’s stature will most likely continue to grow in future years as more and more critical studies of his work continue to appear. The year 2013 saw the release of a wonderful new documentary film, Roque Dalton: fusilemos la noche [Roque Dalton: Let’s Shoot the Night], by Austrian film-maker Tina Leisch. Dalton’s “novelesque” life continues to provide raw material for fiction writers, as in David Hernández’s Roqueana (2014) as well as in Manlio Argueta’s Los poetas del mal (2013)

And despite all of this, the open wound that remains regarding the circumstances of Dalton’s death and the issue of accountability will continue to be an obstacle for those who wish, first, to bring to light the true literary greatness of his work, and second, for those who feel that he has much to teach us about how the left can move forward within the current historical juncture (for example, by learning to use the liberating power of humor).

I evoke this situation in the paradoxical title I have chosen for this essay. Here we have an extraordinary legacy still waiting to be explored fully, yet a terrible wound mars it, one that has not yet healed after forty years. No one, including the Dalton family, believes that those responsible for Roque’s death will ever be put on trial and punished the way they deserve. But some form of transitional justice, perhaps a Truth Commission with good-faith participation on the part of those who have been accused, would go an enormous distance towards finally closing that wound. And what would probably heal it completely would be a sincere public apology from the guilty parties once they reveal the complete truth of what happened—no more weasel words regarding “youthful errors” or “military tribunals.” Then, and only then, will the full magnificence of Dalton’s legacy be able to shine forth unimpeded. A scar would still remain, but some scars can be beautiful…

Spring 2016, Volume XV, Number 3

James Iffland is a professor of Spanish and Latin American Studies at Boston University. He is currently at work on a book on Roque Dalton. He was the 2005-2006 Central American Visiting Scholar at DRCLAS.

Related Articles

The Boy in the Photo

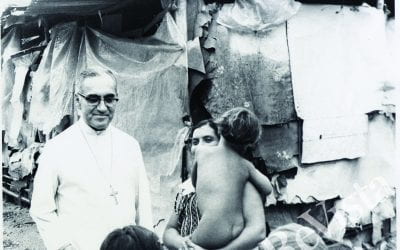

The mangy dogs strolled everywhere along the railroad track. I remembered dogs just like them from the long-ago day in La Chacra in 1979 with Archbishop Óscar Romero, just months before he was killed…

Beyond Polarization in 21st-century El Salvador

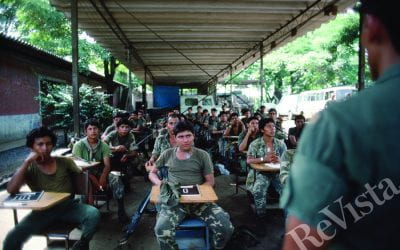

My father was a civil engineer who worked for the government during the civil war years. He specialized in roads and had to spend several days a month traveling to remote places in El Salvador. I was 10 in 1986, and I remember my mom asking my dad…

El Salvador: Editor’s Letter

I had forgotten how beautiful El Salvador is. The fragrance of ripening rose apples mixed with the tropical breeze. A mockingbird sang off in the distance. Flowers were everywhere: roses, orchids, sunflowers, bougainvillea and the creamy white izote flower…