Salvadoran Refugees in the Camp at Colomoncagua, Honduras, 1980-1991

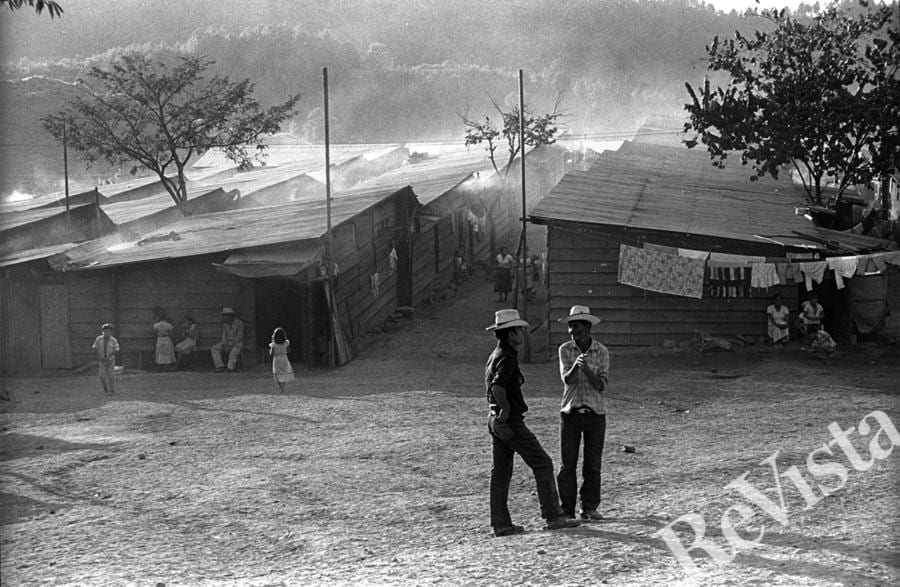

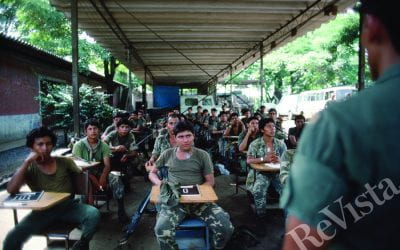

In 1980 and 1981, more than 35,000 refugees fled from Salvadoran military actions into Honduras. In the mountainous northern part of Morazán department, the military’s scorched-earth campaign resulted in about 9,000 people fleeing El Salvador to the Honduran border town of Colomoncagua. The Morazán attacks are best known for the infamous massacre at El Mozote, which left only one known survivor, but there were a number of less well-known massacres, causing the Honduran camp to swell. By 1981, refugees concentrated in a camp near the town, administered by the United Nations and surrounded by Honduran military, were permitted to leave only with special permission—usually for medical emergencies.

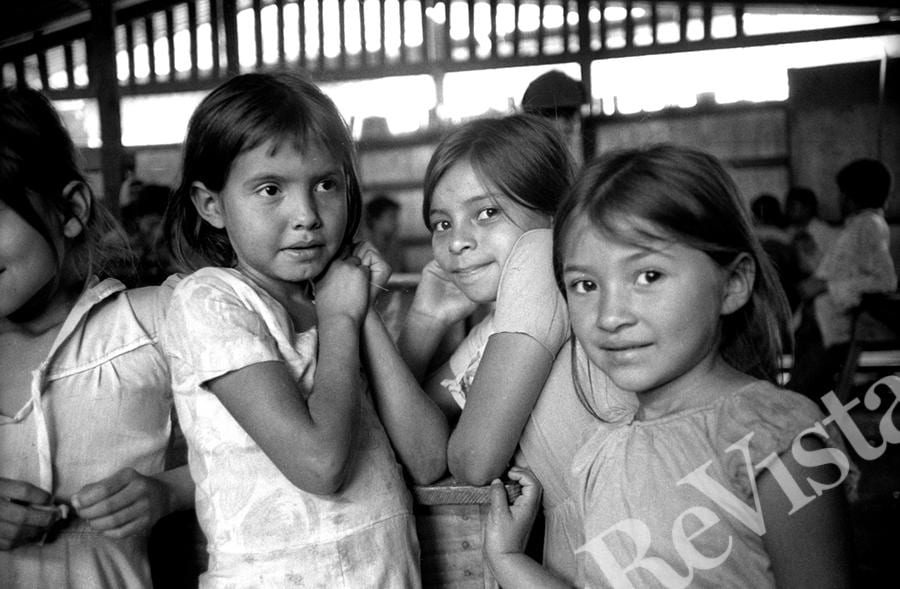

The refugees came from one of the most remote areas of El Salvador. They had lived in widely scattered family units. Children grew up knowing only siblings and cousins, and had little if any schooling. The soil was inadequate to support the traditional basis of Salvadoran rural life, the milpa (corn field), and frustrated farming efforts left people increasingly poor over the generations. Men supplemented family incomes by migrating to work in coffee plantations. Mistreatment and repression by the representatives of El Salvador’s notorious oligarchy and by public institutions were widely felt and resented.

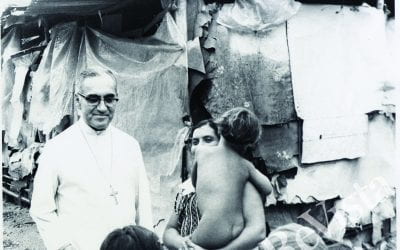

In these conditions, liberation theology found a ready audience, as did the revolutionary politics of the groups that would become the FMLN. The two liberatory messages reinforced each other. The response of the Salvadoran government to the increasing radicalization of the countryside was to launch a widespread military repression. While peasant communities suffered, the military was not ultimately successful, and in areas like northern Morazán, the counter-thrust by guerrilla forces pushed the army back and established a substantial area that remained under guerrilla control for the duration of the internal conflict.

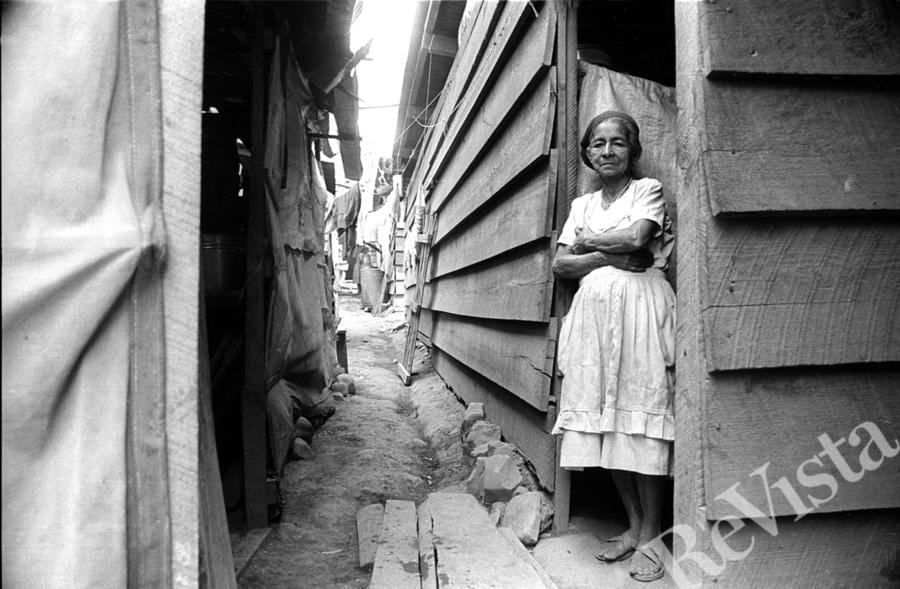

Meanwhile, the refugees in the camp at Colomoncagua faced a situation totally new to them. With the clandestine leadership of guerrillas of the ERP (one of the five guerrilla groups in the FMLN), who slipped in and out of the camp through the Honduran lines, the refugees had to create new social structures that would support life in their now crowded conditions. They had to learn how to live without land, unable to practice the agriculture that had been at the center of their family economy and culture. And they had to face life as people newly dependent on the support and solidarity of international agencies and organizations that worked with the camp.

Within these strange and difficult conditions, a perhaps surprising set of changes turned out to support very positive developments. Indeed, looking back on their decade-long stay in the camp after the war ended, some of the former refugees saw their time in the camp as a “golden age.”

With the support of the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and a few European and North American NGOs, the refugees created several sub-camps, which they called colonias, the Salvadoran term for neighborhood, constructing dwellings, buildings for workshops, classrooms, nutrition centers and health stations, nurseries, a chapel, latrines and small gardens and barns.

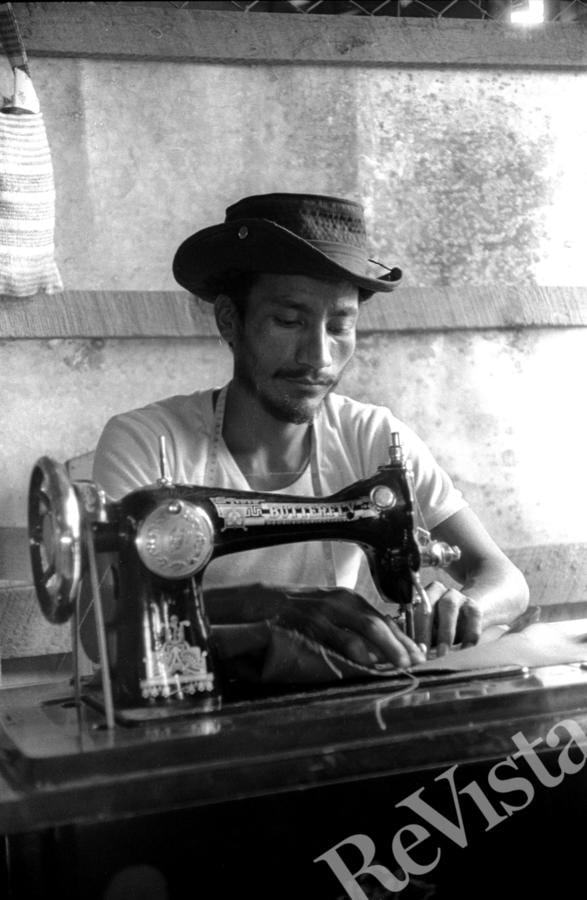

They developed a set of productive workshops, where men, women and children (when they were not in school) worked together. These produced furniture, clothing, shoes, hats, hammocks, metal utensils (bowls, pitchers, buckets) and other items. The refugees were learning genuine skills, both occupational and social.

One emblem of change was the tortilla workshop. Here women made tortillas as an occupation, a job. In addition to creating a new social respect for this skill, the workshop freed the great majority of women in the camp from this task, allowing them to participate in non-traditional work and new social and leadership roles.

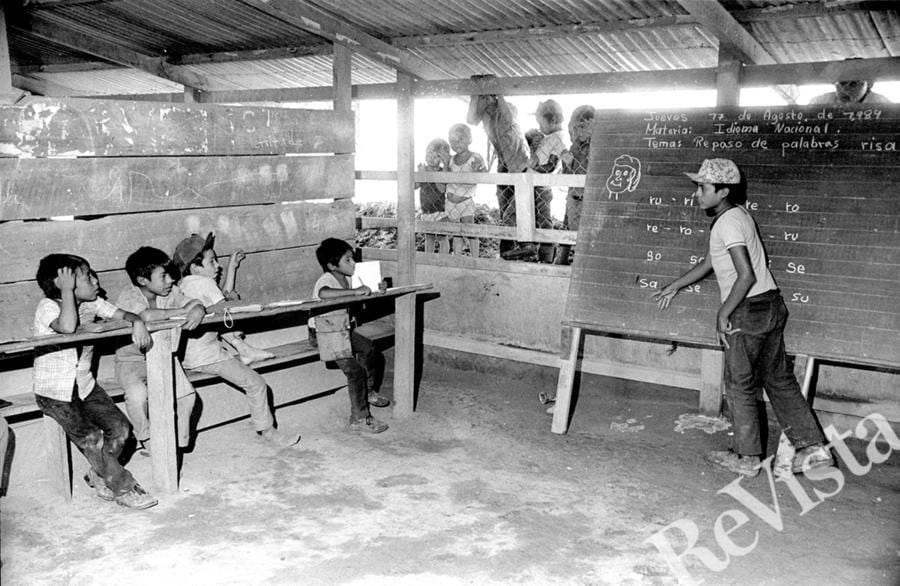

Some refugees functioned as teachers, sanitary workers, social workers and child-care workers. These latter would organize the children in the morning to make sure faces and hands were clean and teeth brushed, and they would look for kids who were not in the classes where they belonged

No one was paid for their work—work provided meaning in people’s lives, and the products were distributed according to need. When donations arrived—corn, vegetables, pigs, household goods—they were carefully measured and divided among the families.

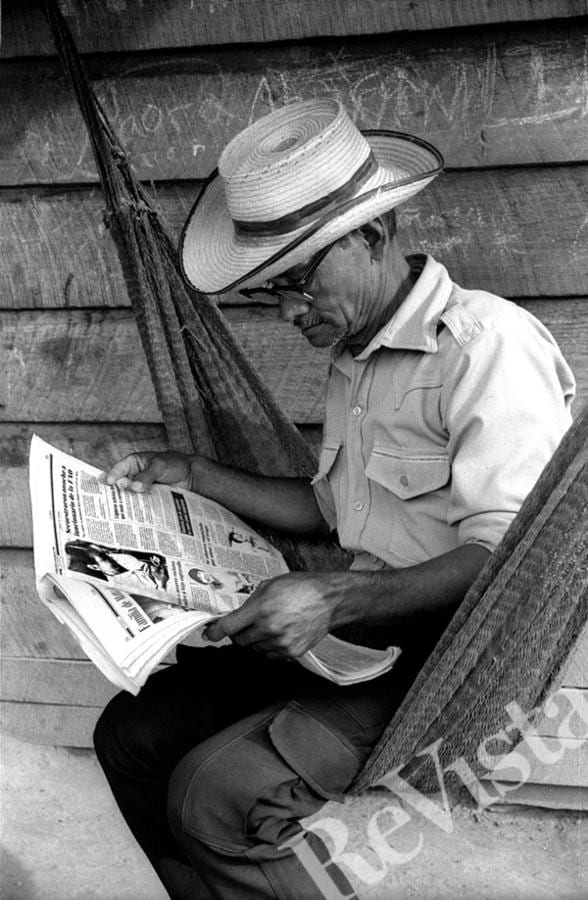

Like other newly literate people, the refugees were thirsty for reading materials—newspaper, magazines and books brought to the camp by visitors were eagerly received and passed from hand to hand.

In addition to new occupational and social skills, the refugees learned about self-governance, and the camp was run internally by an elaborate structure of committees and boards. Through their experiments in self-governance the refugees became an organized group, and developed confidence and strength that served them in their negotiations with the Honduran and Salvadoran authorities, representatives of UN agencies and NGOs, and others.

One of the important demands the community made was that the international agencies not provide teachers and leaders for the workshops, but rather that they train refugees to perform these roles. So in the classrooms the teachers were refugees—often, young children teaching their elders to read—and in the workshops production was organized and led by refugees.

There was of course an underlying problem waiting to emerge. The materials and expertise that supported the achievements of the community were provided for them by the various agencies—and they were put to very good use. But later, when the community would have to move from this dependency to independent development, some new behaviors would have to be learned, and some others unlearned.

In the last couple of years in the camp, there was pressure from the Honduran authorities and UNHCR to repatriate the refugees to El Salvador, but as individual families. They, however, insisted on waiting until they were ready to repatriate as a community. Their strength was a source of conflict with some NGOs, which were more accustomed to treating people as victims and dependents, and not as partners.

In 1989, the community decided to return to the war zone in Morazán and create a new community, named for F. Segundo Montes, one of the priests murdered by the army at the UCA , who had a long relationship with the community. In a major operation by the two governments, the UN and NGOs, the refugees and everything they owned—including the boards and nails of their dwellings—were transported to their new home.

Once in Morazán, the community faced a new set of challenges: trying to recreate the social environment of the camp within a totally different context; operating the workshops as enterprises within a cash economy; responding to the military activities around them; and more. One young grass-roots leader told us, “We lived for ten years in exile…We learned so much…If we had lived longer in [El Salvador], it would have been more difficult to become organized, to think about serving the community….We [youth] have come back into a capitalist system, the same one our parents lived in, but we’ve had the experience of being in an autonomous community, of deciding for ourselves what our values are.” They were conscious of the enormity of moving from dependency to development, and they knew that a new chapter in their story was opening. A grass-roots member of the new community said to us, “Why are you writing a book about us now? We are just beginning—you ought to wait a few years.”

Spring 2016, Volume XV, Number 3

Steve Cagan is an activist photographer who has been doing projects in Latin America for more than 30 years. His 1991 book, This Promised Land, El Salvador, written with his wife, Beth Cagan, was Book of the Year of the Association for Humanist Sociology, and was published in San Salvador as El Salvador, la tierra prometida. He can be reached at steve@stevecagan.com or www.stevecagan.com.

Related Articles

The Boy in the Photo

The mangy dogs strolled everywhere along the railroad track. I remembered dogs just like them from the long-ago day in La Chacra in 1979 with Archbishop Óscar Romero, just months before he was killed…

Beyond Polarization in 21st-century El Salvador

My father was a civil engineer who worked for the government during the civil war years. He specialized in roads and had to spend several days a month traveling to remote places in El Salvador. I was 10 in 1986, and I remember my mom asking my dad…

El Salvador: Editor’s Letter

I had forgotten how beautiful El Salvador is. The fragrance of ripening rose apples mixed with the tropical breeze. A mockingbird sang off in the distance. Flowers were everywhere: roses, orchids, sunflowers, bougainvillea and the creamy white izote flower…