Sandoval Redux

“While I lie on a cushion of worm slime, Father Alonso de Sandoval appears”: So remarks one of the several enslaved narrators in Afro-Colombian author Manuel Zapata Olivella’s 1983 novel Changó, el gran putas, translated into English in 2010 by Jonathan Tittler as Changó, the Biggest Badass.

Zapata Olivella thereby reimagines— on the granular level of everyday intimate contact—the life and work of the Jesuit missionary Alonso de Sandoval (1577- 1652), whose theological writings betray the profound moral contradictions and epistemological blindspots at the heart of his Christianizing project.

This conflict surfaces in the second section of the novel, “The American Muntu,” as newly arrived African slaves in the Colombian port city of Cartagena de Indias encounter the proselytizing zeal of the Society of Jesus—which, from its founding until its ultimate expulsion from Spanish America in 1767, was among the largest slaveholders in the Americas. Father Sandoval’s entrance onto the stage of Zapata Olivella’s novel is shaped both by coercion and elation. His commands— “‘Open your mouth and drink,’” “‘Suck on this grain of salt,’” “‘Receive the Lord’s grace’”—receive no verbal response until the nameless speaker, regaining his voice from extreme thirst, speaks to Sandoval “‘in his own tongue.’” The renowned Jesuit missionary exclaims excitedly “You are a Christian! Praise the Lord!” and “jumps for joy.” Zapata Olivella continues:

I don’t know how much he paid for me or if he managed to beg for my freedom. He himself, pulling the cart that transports the sick, takes me through the door that used to open only to vomit out the dead. […] While Moncholo shoos the flies from my face, Father Alonso brought some oranges.

Splitting them open with his fingernails, he squeezed their juice into my mouth. Only at that moment, when life ripped off my death mask, did he recognize me.

This failure of recognition—Sandoval’s delayed realization that the nearly dead gure before him is no anonymous bozal but rather a former colleague of sorts, an enslaved translator who had helped the “novice” during his early missions to the African continent—structures the entire section of Changó. This collision of the priest’s triumphal joy and the stoicism of now-named Domingo Falupo (“we suffer very little and feel only the affliction and joy of the dead”) establishes a spiritual con ict hardly legible in Sandoval’s own writings on slavery.

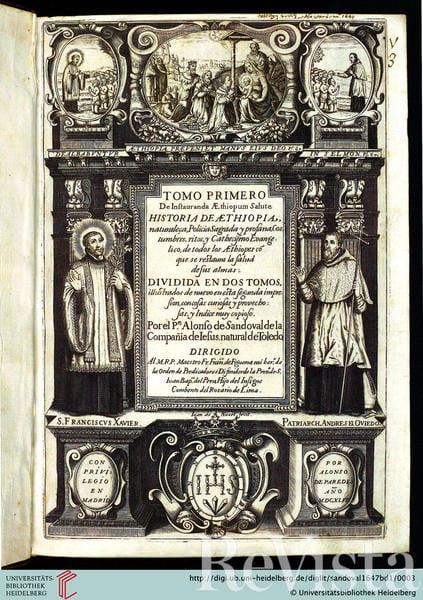

First published in Seville in 1627 as Naturaleza, policia sagrada i profana, costumbres i ritos, disciplina i catechismo evangélico de todos etíopes, Sandoval’s magnum opus is a thoroughly hybrid text. Book I of the so-called Treatise on Slavery describes African geography, languages, cultures, religions and dress in an ethnographic style typical of 16th- and 17th-century missionary writings, whereas Book II argues that slaves’ suffering is rooted primarily in their ignorance of the Christian God. Book III provides instructions for baptizing and catechizing enslaved Africans, paying particular attention to the logistical difficulties posed by linguistic difference. Book IV, moreover, largely abandons the previous focus on the plight of enslaved Africans in Cartagena and instead articulates a global vision of Jesuit mission work—and its spiritual and ethical imperatives—across the Americas, Africa and Asia.

Known more commonly as De instauranda Aethiopum salute (“On restoring salvation to the Africans”)—the Latin title affixed to an augmented 1647 edition of the text published in Madrid—Sandoval’s work frequently includes material gathered from daily interactions with enslaved Afro-Cartagenans, whose voices are ventriloquized and refracted in the body of the text. In the chapter “The Slave Ships,” for instance, Sandoval writes of the Middle Passage: “I know individuals who have endured this journey. They say they are extremely cramped, nauseous and mistreated.” Evidently basing his description on accounts told to him by enslaved people themselves, Sandoval considers how Africans’ testimony of the transatlantic crossing has altered his own perception of the trade. “The slaves look forward to eating once every twenty-four hours, although they get no more than a half cup of corn or crude millet and a small cup of water. Other than that, they get nothing else besides beating, whipping and cursing,” he continues. “Many people I know have experienced this, although I once believed that some of the slavers treated them more gently and kindly these days.”

But the Treatise is no anti-slavery text. Sandoval himself recognized the ambivalent position of Jesuit missions striving to baptize, catechize and spiritually purify newly disembarked African slaves while working within institutions that depended upon their bondage. The college in Cartagena where Sandoval worked owned several haciendas, including La Ceiba—where sugarcane and cattle were raised—and its two satellite tile factories (tejares) Alcivia and Preceptor, where 111 slaves were employed at the time of the Jesuit expulsion from the Americas in 1767.

This state of affairs was neither paradoxical nor hypocritical according to the theology of Sandoval and his Jesuit colleagues, the most famous of whom— Sandoval’s apprentice and “companion” Pedro Claver, another character in Zapata Olivella’s novel—was ultimately beatified in 1850 and canonized in 1888 for his spiritual work among African slaves in Cartagena. The Society of Jesus, while recognizing the misery of their African subjects, did not seek in any demonstrable way to protest, curb or even seriously question slavery itself; they perceived the pagan bozal as capable of spiritual redemption through baptism, catechism and confession.

Indeed, Sandoval is at pains throughout De instauranda to distinguish his own benevolent practices from forms of mass conversion carried out before disembarkation from the African slave coast. In one striking passage, Sandoval relates how Africans aboard slave ships or held captive at slave ports understood their forced baptisms. “Some respond that they are afraid of this water and believe the whites do this to kill them. Others think that the water is like a brand, a mark put on them so that their masters know who they are when they buy and sell them,” he writes. “One slave told me that water was poured on him to enchant him, to prevent him from rising up against the whites in this ship in the course of the voyage. He also thought it was done so he would live many more years and bring gold to his masters.”

In contrast to these images of coercion, Sandoval depicts his own baptismal practices as moments of celebration. “Miguel feels so much gratitude for the benefits of baptism that to this day, whenever he sees me he stops before me, falls on his knees, and claps his hands as a sign of joy,” he writes of one encounter. “Then he asks me for my hands and puts them over his eyes, and then he gets up and goes on his way.” Here, the “joy” of an enslaved African named Miguel at the prospect of spiritual salvation re ects the ctional Sandoval’s “jumps for joy” in Zapata Olivella’s novel written across a gulf of three hundred years. But Changó foregrounds and excavates this misrecognition at the heart of Sandoval’s Christianizing enterprise.

Structured like the Treatise in several discrete sections, the novel narrates the history of the African diaspora—what Zapata Olivella calls the ekobios—through key moments of insurgent conspiracy, political revolution and outright rebellion: an uprising aboard a slave ship; the Maroon wars in 17th-century Cartagena led by religious heretic Benkos Biojo; the Haitian Revolution, as narrated by Toussaint Louverture, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and Henri Christophe; the Latin American wars of independence, featuring appearances by Simón Bolívar, José Prudencio Padilla, and José María Morelos; and finally a near-parodic gathering of prominent black Americans— including Nat Turner, Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Tubman; Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Du Bois and Marcus Garvey; and Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, and Claude McKay—told through the fictional character Agne Brown, a young Columbia University anthropologist and spiritual medium likely modeled on Zora Neale Hurston.

Zapata Olivella splices his rendering of early modern Cartagena—where slave and free Africans conducted a series of battles in order to establish and defend their own free town (Palenque) at San Basilio, a small village amid the foothills south of the city— with the judicial language of Inquisition tribunals. He writes:

For being a proven and confessed fornicator with four burros, Antonio Bolanos was condemned to one hundred lashes and public shaming as a lesson to the Africans who, having received holy baptism, feign practicing the faith, going to mass, confessing, and taking communion in order to make a show of being good Christians, but who, in their hidden life practice the most nefarious concupiscence and obscenities learned from their elders.

The joyous redemption described in Sandoval’s text is here rendered as subterfuge, and Domingo Falupo is the culprit. The translator himself is brought before the Inquisition:

It is ordained that all the baptisms in which the Moor Domingo Falupo participated to be subject to review, because of his tergiversation in bad faith of the questions that through his mediation were asked of the Africans….

For all of the above, it would be appropriate to obtain from the reprobate a complete and candid confession and, if said confession should prove to be contrary to our aims, to cloak it in the greatest secrecy, lest a wave of disbelief was over the baptisms veri ed by the company, with those who are sincerely and really Christians being taken for Moors, and the most abominable reprobates being taken for Christians.

Father Sandoval then reappears, this time as a “Friendly Shadow” who is “buried in Seville and is only retracing his footsteps in Cartagena,” imploring Falupo to appease the Inquisition and reveal “whose baptisms were done sub conditione of your wayward conduct.” Echoing their initial (re)encounter, the priest meets the same response. “‘In my silence you will nd my answer,’” Falupo remarks. “‘None of those ekobios who speak languages unknown to you and to your interpreters, for whom I served as interpreter, disavowed their Orichas.’” With that, Sandoval’s “grieving” ghost retreats from Falupo’s cell “as if it really had been his body and not his Shadow that entered therein.”

Changó thereby enacts a narrative repetition that signi es, in miniature, the novel’s broader historical reenactment. The surreal return of the gure of Father Sandoval within the spiritual world of the text ripples outward as Zapata Olivella’s implicit conjuring of De Instauranda. If the Treatise surprisingly comprises an ethnographic repository for the memories and beliefs, joys and terrors of enslaved Afro-Cartagenans under Sandoval’s spiritual supervision, it also spurns the possibility of their duplicity, fugitivity, or resistance. Zapata Olivella’s novel reimagines that misrecognition between Jesuit priest and pagan slave not as a momentary lapse ultimately to be reconciled, but rather as a fundamental precondition for the history of the African diaspora in the Americas.

Winter 2018, Volume XVII, Number 2

Nicholas T Rinehart is a doctoral candidate in English at Harvard University. His writing has appeared in Transition, Callaloo, Journal of Social History, and Journal of American Studies, with additional pieces forthcoming in MELUS, the Dictionary of Caribbean and Afro-Latin American Biography (Oxford UP), and the Cambridge Companion to Richard Wright. He is also a co-editor, with Wai Chee Dimock et al., of American Literature in the World: An Anthology from Anne Bradstreet to Octavia Butler (Columbia UP, 2017).

Related Articles

Afro-Latin Americans: Editor’s Letter

My dear friend and photographer Richard Cross (R.I.P.) introduced me to the unexpected world of San Basilio de Palenque in Colombia in 1977. He was then working closely with Colombian anthropologist Nina de Friedemann, and I’d been called upon by Sports Illustrated to…

Witches, Wives, Secretaries and Black Feminists

The issue of gender has been front and center for me, both as a subject of my fieldwork on black politics in Latin America, and how I conducted that research, particularly in how I…

Compañeros En Salud

English + Español

I have lived in non-indigenous rural Chiapas in southern Mexico since 2013, working with Compañeros En Salud (CES)—a Harvard af liated non-profit organization that partnered with…