Botanical Studies in Nicaragua

An Ongoing Journey of 50-Plus Years

The mountainous areas of northern Nicaragua finally felt safe enough to roam around after more than forty years of war. What we—two biologists—found was a treasure of unknown and rich plant diversity and beauty where the plants had not been seriously explored for decades.

In 2010, when we first drove into the area in our 2009 Toyota Hilux, we found vast local forests mostly composed of pines and oaks on granite mountains and seemed so well preserved that we immediately wanted to survey it.

The region’s flora and fauna were preserved by the wars that the country endured between the 1960s and the 1990s, serving first as a refuge for the Sandinista movement fighting the Somoza dictatorship and later, after the Sandinistas were in government, sheltering the Contra guerrillas trying to overpower the Sandinistas.

Now, during the past decade, we’ve conducted several expeditions to the region, including the exploration of Cerro Mogotón on the Honduran border, the highest mountain in Nicaragua (7,000-feet, about the height of Mt. Hesperus in Alaska). To reach the peak we planned a three-day trip, and, together with Nicaraguan colleagues, advanced on foot towards the summit on a steep and sometimes hazardous trail. Because of the rough terrain and the strong winds and torrential rains, camping was a challenge, but finally we managed to find a not-so-bad spot and to set up a camp to spend the night. The following day, as we reached the highpoint of Mogotón, we came to realize that the upper part of the trail had been mined during the war, and although the government had conducted de-mining operations, the danger still persisted and the only way to work there was by staying within a few meters from the trail.

However, despite the difficulties, we were rewarded with encountering a wealth of interesting plants, some of which we had never seen before in any other part of Nicaragua. Among the many discoveries, we found unusual blueberries, cherries, and wild avocado relatives that are food for the resplendent quetzals.

The adventure of exploring Nicaragua and studying its plants began for one of us (WDS) on January 26, 1969, when, as a first-year graduate student at Michigan State University, I collected my first plant specimens on the beach in Masachapa. The trip back to the pensión beside the TicaBus station in old (pre-earthquake) Managua was in the bed of a pickup truck, and the most important lesson of the day was that Nicaraguans are among the friendliest people in the world.

Flashing forward eight years, as I finished up my graduate studies, I was hired by the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis, Missouri, to write a compilation of the plants of Nicaragua. Plant biologist and philanthropist Boris Krukoff had provided funding to Peter Raven, then Director of the Missouri Botanical Garden, to start a project to study the plant diversity of Nicaragua. Krukoff, who had fought with the White Russian Army, eventually making his way to New York where he became wealthy working with Merck in plant exploration, had realized that the plants of Nicaragua were the least known in Central America.

Thus, in July 1977, I returned to Nicaragua, where I developed a long-lasting partnership with the government, notably with Jaime Incer, who both as a public and private person has dedicated his life to conservation in Nicaragua, and with a few academic institutions that survived the political turmoil. I began the project with the goals of conducting a floristic inventory, establishing an herbarium to safeguard the specimens collected, training a cadre of Nicaraguan botanists and publishing a Spanish-language manual of the plants.

The first botanical collections in Nicaragua were made by Mexican physician José Mociño in 1795, although only drawings and no actual specimens survive. The oldest extant specimens were gathered by botanists on the English expedition “Voyage of the Sulphur” in April 1837. After that, a series of European and later North American botanists gradually brought the number of collections to around 20,000, representing about 1,000 plant species.

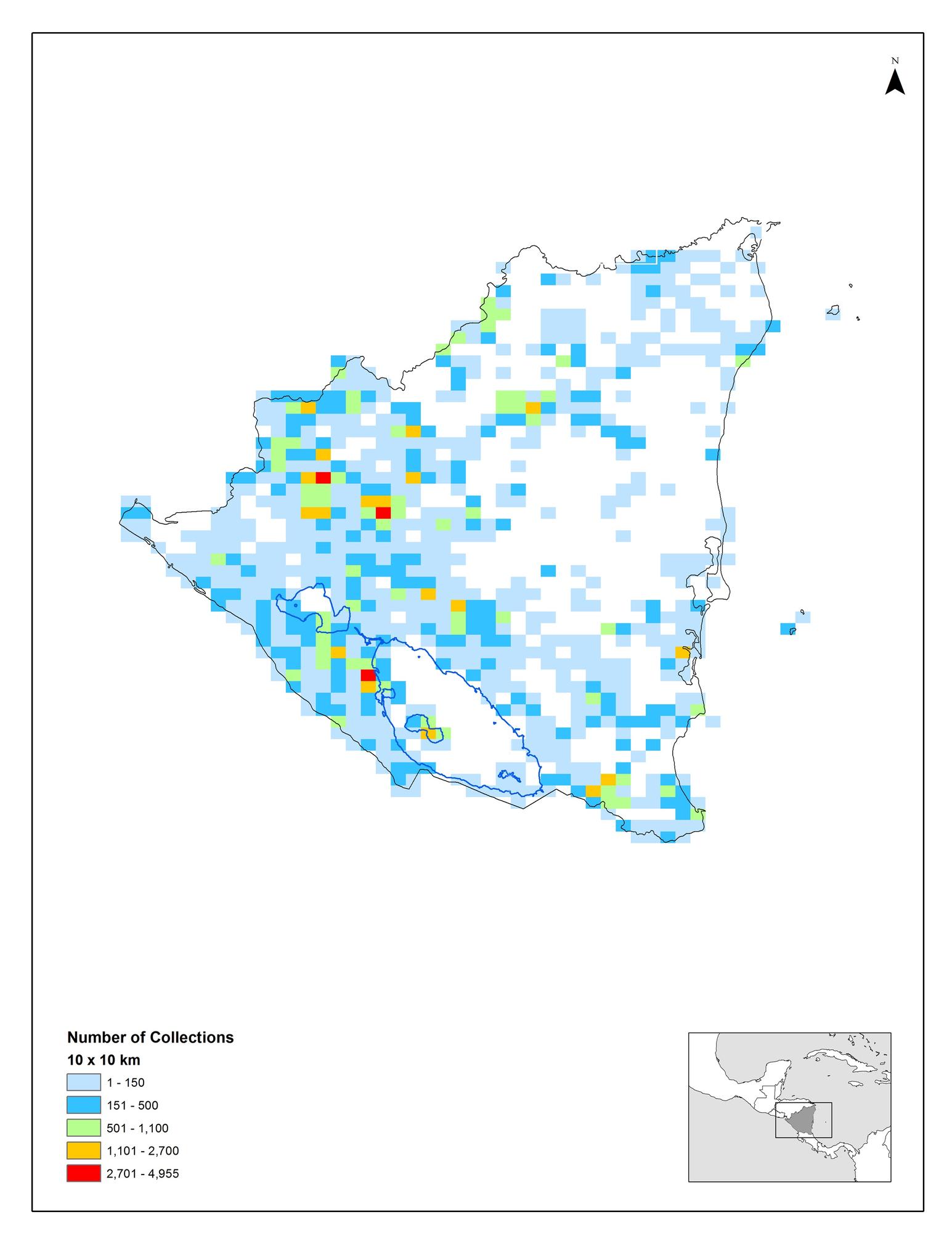

This was the situation in 1977, when the project that we named “Flora de Nicaragua” began. To date, through our efforts and those of an excellent group of dedicated Nicaraguan botanists, the country has a total of about 160,000 collections of plants, representing about 7,900 different species. Nicaragua probably still qualifies as the least-well botanically inventoried country in Central America but the situation has dramatically improved.

Inventorying Nicaragua during a time of war was complex and quite dangerous at times. The regions that were safe were better surveyed, but war zones were pretty much off limits. Thus, when the Flora de Nicaragua books were published in 2001 and 2009, they described only 6,479 of the 7,900 plant species we know to exist in the country today. Large swaths of land, in particular in the north and on the Atlantic slopes, remained under-explored. In the early 1980s, when it was still possible to travel in these regions, we were able to conduct a few expeditions that allowed us to document some of the flora, but also illustrate cultural aspects of a region that later was devastated by conflicts. Along the most isolated areas of the Bocay and Waspuk rivers we found not only interesting plants, but also isolated people (Mayagna) unaccustomed to outsiders. In Pearl Lagoon, there were thriving populations of Garifunas and Miskitos, and we located the southernmost pine savanna, and therefore the southernmost native pines in the New World. In Rama Key, we met a few generations of the Rama people who lived on a 55-acre island in the Bay of Bluefields on the Caribbean coast.

Río Bocay, moist forest on limestone.

Man in house on Corn Island, in the Caribbean.

Pine savanna near Pearl Lagoon, this population of Pinus caribaea represents the southernmost extension of native pines.

Inundated pine savanna near Pearl Lagoon, with small islands of the palm Acoelorraphe.

Old woman and children on Rama Key.

These investigations resulted in a three-volume Flora de Nicaragua (2001) and a subsequent volume on ferns (2009) simultaneously published on-line and steadily updated since then. All native species in the on-line version [http://www.tropicos.org/Project/FN] have an estimated conservation assessment, distribution maps and graphic elevation ranges and phenology. About half of the species are illustrated with photographs. In the preface to the Flora, Peter Raven, one of the world’s most famous plant biologists and conservationists of our times, wrote: “Nicaraguan plants are a priceless part of the heritage of all Nicaraguans, and the Missouri Botanical Garden presents these books as a gift to the people of Nicaragua, so that they will use the knowledge contained in them in such a way as to enhance the lives of generations as yet unborn.”

The Flora project began before the era of personal computing, and the data compilation was started on 3X5 cards, migrated through a variety of hardware and software and eventually became part of TROPICOS, the Garden’s massive plant database available on the web. Many European herbaria were combed through for historical records of Nicaraguan collections. Thus, the database of Nicaraguan collections represents the great majority of all collections ever made in the country. Using printed maps in the early days and later GIS devices, we have been able to geo-reference most of the collections, and this data has become an important tool, available on-line to all interested parties, for further studies of Nicaraguan plant diversity and for the overall understanding of the vegetation. Additionally, this data can be mapped to pinpoint regions rich on plant species and to understand what areas of the country are repositories of the most rare or threatened plants. All in all, the data can guide subsequent field work to continue the process of refining the plant information of Nicaragua, and can also serve as a basic and reliable source for saving rare plants, finding wild relatives to domesticated plants, and other projects. These additional tools have made exploration more efficient and about 1,400 species have been added to the known diversity since the publication of the Flora. A map,produced from the current data, shows where plants have been collected.

Map of plant collections in Nicaragua.

Nicaragua is not immune to the effects of global climate change. Rising sea levels, shifting rainfall patterns and temperature variation will have predictable and unpredictable consequences for many aspects of life, including agriculture, water availability and human diseases. Although perhaps trivial on a grand scale, the flora of the country will also change. During the last ice age, the vegetation of North and Central America shifted southward in a colder world. Some kinds of plants successfully migrated southward through Central America and spread along the Andes in South America. The migration of many other temperate plants, however, was blocked by the lack of high mountains in the southern half of Nicaragua, the so-called “San Juan Depression,” and reached no further than northern Nicaragua.

Bonellia nitida, a rare tree restricted to dry mountain forests in Central America.

Bidens oerstediana, an annual tickseed species only found on basalt lava flows in Nicaragua and adjacent Guanacaste, Costa Rica.

Robinsonella erasmi-sosae, a rare dry mountain forest tree found only two localities in northern Nicaragua and in adjacent Honduras.

As the world warmed after the last ice age, the temperate plants migrated back northward but many relicts remain in northern Nicaragua. The most conspicuous of these relicts are pines, which reach their southern limit in Nicaragua but dominate much of the vegetation in the northern mountains. These many temperate relics, including members of the blueberry family, beech family, walnuts, oaks and sweet gum, cumulatively form a significant component of the vegetation. These plants were already in a climatically precarious situation, surviving in the most temperate refuges, and rising temperatures will only accelerate their march northward, and thus their disappearance from the flora. In the southeast of the country, with the vegetation dominated by wet forest immigrants from the Amazonian flora, the more significant issue is probably precipitation. The total rainfall there is currently about half of that recorded in colonial times, although it is not clear how climate change will affect future precipitation. It does seem to be clear that hurricane frequency and strength is increasing and over time that will alter the landscape, if perhaps not the floristic diversity. We estimate that perhaps 30-40 plant species are extinct in Nicaragua, not seen in the country for over 100 years despite repeated searches, but the number of extinct plants will surely begin growing rapidly.

Conservation in under-developed tropical countries is always a challenge. A first step in conservation may be inventory— based on the logic that you cannot begin to protect, nor evaluate your progress, until you know what you have. Another approach is landscape conservation in which diversity in certain patches of land is generally protected as a unit. A variety of protected areas, public and private, large and small, have been designated in Nicaragua. Of the government-administered areas, probably only Volcán Mombacho (cloud forest) and Volcán Masaya (dry forest) can be considered success stories, in large part because both are important tourist destinations that provide the financial incentive for protection.

The two large Biosphere Reserves on the Atlantic side, Bosawas and Río San Juan, lacking this incentive, are being rapidly lost to the agricultural frontier, first through the extraction of timber and then through the conversion of reserve land to cattle pastures and subsistence farming. We have dedicated ourselves to the inventory approach, first by scientifically documenting plant diversity and then evaluating the risks to the individual species survival. Nicaragua, in the center of Mesoamerica, is very much a bridge between the plant assemblages of North and South America. One out of every four plants, largely in the north, have affinities with North America and one out of every five have affinities with South America. However, more than one out of every three plants do not resemble those in either North or South America, and the rest are found only in Mesoamerica. About one percent of the plants of Nicaragua are endemic, found nowhere else, but about ten percent more are found in adjacent Honduras and/or Costa Rica. Obviously, we focus on these endemic and narrowly distributed plants because they are likely to be the most endangered. Perhaps not surprisingly, the most endangered plants are not well represented in the currently protected areas.

Nicaragua now has an up-to-date inventory, the Flora, three active herbaria and a dedicated and capable group of botanists. Our efforts to increase the scientific knowledge of plant diversity in Nicaragua have paid off, but the most important contribution is helping to build a cadre of local and committed biologists, who in turn are training the next generations. After all, it is the next generations of Nicaraguans who are the hope for conservation. We will continue our work in collaboration with them and with the local institutions and botanists, and hope for the best.

Spring/Summer 2019, Volume XVIII, Number 3

Olga Martha Montiel is Vice President for Conservation and Sustainable Development and Director of the Latin American Research Program at the Missouri Botanical Garden. She is an editor of the Flora de Nicaragua and together with Warren Douglas Stevens continue to work on plant conservation in Nicaragua.

Warren Douglas Stevens is a Curator at Missouri Botanical Garden and an editor of the Flora de Nicaragua. Besides studying the Central American flora and working on plant conservation in Nicaragua, he also is a specialist on milkweeds (Asclepiadoideae).

Related Articles

The University and the Nicaraguan Crisis

English + Español

University youth were the first to rise up in April in Nicaragua. Then other young people followed en masse, followed by the rest of the population. The young students woke up an entire country. “They are students; they are not delinquents!” became the first slogan that…

Nicaragua TEMPLATE: Single Language Article

English + Español

A one or two sentence blurb about the article

3, 2, 1… poemas

Manual para sobrevivientes…