Cachupa

CUISINE AND COMMUNITY

Isabel Ferreira, known around the Harvard community as the language instructor who teaches Portuguese for Spanish speakers, is used to crossroads. Born in Portugal, she moved to Mozambique when she was three weeks old and spent most of her childhood shuttling from her mother’s native Cape Verde and countries in Africa, where her father worked with the colonial administration.

Yet the smell of cachupa, a corn-based beef boiled dinner, mixes in her memory with the aroma of mangos, big mangos, small mangos, long mangos, a childhood smell independent of any country and linked to a sense of home and a community of women.

While Ferreira played with other children around the mango and banana trees, her mother and other relatives would cook the cachupa outdoors in a huge clay pot over an open fire. White and yellow corn similar to hominy would be boiled for hours and hours. The corn which is not native to the Cape Verde Islands was prepared in a very special way, pounded and pounded until the edges became roundish and smooth; then beans such as lima beans were added, and then pork, beef, chicken, yams, and vegetables such as turnips, potatoes, and cabbage. There was always a lot of peeling and cutting and talking and singing.

Ferreira loved to watch as the women sang traditional Cape Verdean songs in Creole. When she was six or seven, she began to help cut vegetables, but mostly she watched and listened.

The cachupa fed 30 people, cousins going back and forth from one island to another, and it was a weekend event. First the outdoor market, then the preparation, and the eating. Even the eating had different stages. Little children could be fed the clear broth. The meat was often separated out and fried the following day with eggs for breakfast, as different cousins drifted in from distant parts. Whenever someone showed up, it was time to be fed.

“It was quite an enterprise,” recalls Ferreira. “Cachupa is a national dish; there’s cachupa pobre and cachupa rica (cachupa for the poor, and cachupa for the rich). Cape Verde is a place of crossing, and I think cachupa reflects that.”

Ferreira, a doctoral candidate in Portuguese at Brown University, often works with notions of domesticity and family, particularly with the representation of Africa in the 20th century Portuguese novel. She is interested in understanding the concepts of home, house, family, and tropicalism, and it all seems to come together with cachupa. She carries on her family’s tradition by preparing vegetarian and non-vegetarian versions of cachupa as an end-of-semester treat for students and will soon be bringing the tradition to the University of Notre Dame, where she will become an assistant professor in August.

Spring/Summer 2001

Related Articles

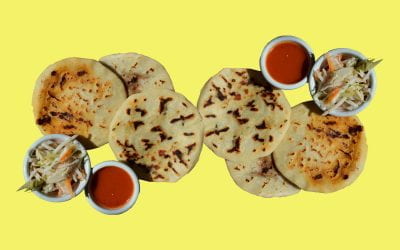

Salvadoran Pupusas

There are different brands of tortilla flour to make the dough. MASECA, which can be found in most large supermarkets in the international section, is one of them but there are others. Follow…

Salpicón Nicaragüense

Nicaraguan salpicón is one of the defining dishes of present-day Nicaraguan cuisine and yet it is unlike anything else that goes by the name of salpicón. Rather, it is an entire menu revolving…

The Lonely Griller

As “a visitor whose days were numbered” in Buenos Aires, Argentina, he tossed aside dietary restrictions to experience the enormous variety of meat dishes, cuts of meat he hadn’t seen…