Children Seeking Asylum

Homeland Security and Child Insecurity

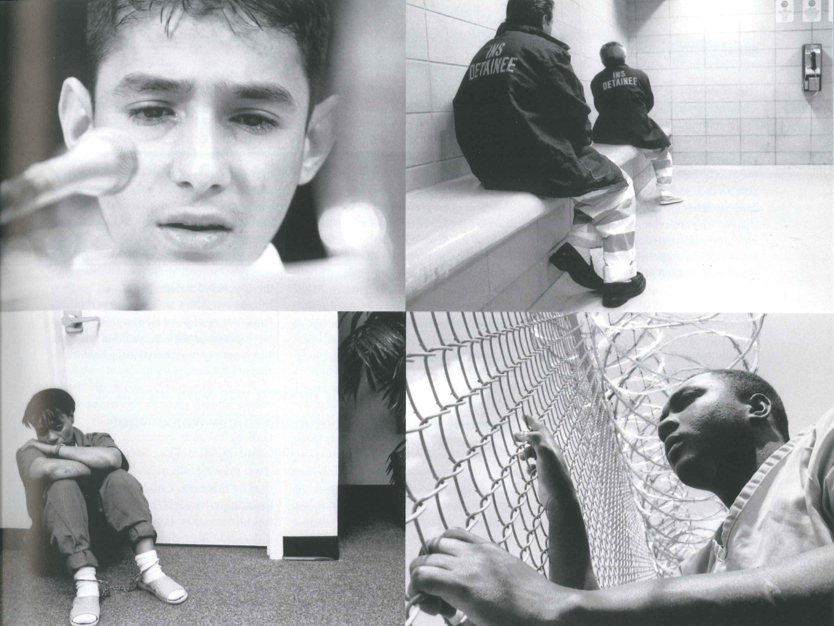

Clockwise from top left: Edwin Muñoz testifies before the US Senate committee; immigration detainees; an asylum seeker; Cuban Julian Gomez in jail.

Edwin Muñoz left his native Honduras at 13 to seek asylum in the United States. Abandoned by his mother as a four-year-old, he had lived with a brutal cousin who forced him to earn money by working on the streets. “When I didn’t earn enough money, he punished me, beating me with a noose, car tools and other objects, leaving scars on my body,” Edwin testified before the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Immigration last year. He had heard “wonderful things” about the U.S. and so eventually he decided to make his way there by begging, working on the streets and walking. But instead of El Dorado, he found more misery. Arrested as soon as he crossed the border, he was jailed in San Diego Juvenile Hall, together with juvenile offenders. He was mistreated by fellow detainees and by the prison guards: “The officers did not know why I or the other children picked up by the INS (Immigration and Naturalization Service) were there. They treated us…as criminals. They were mean and aggressive, and used a lot of bad words. Many of the other boys were violent, frequently looking for a fight”. He applied for asylum and was transported in full shackles every time he was taken to court. Even after he won his asylum case, and was—after eight months in detention—finally released from jail, he was shackled on the way to his foster family. (Amnesty International USA, “Why am I here?” Children in Immigration Detention,” June 2003)

Like Edwin, many children fleeing gross human rights abuses in their home countries fare badly at the hands of U.S. state authorities. In the Los Angeles Juvenile Halls, immigration authorities detain 200 children every year. They come from Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, China, India, the Middle East, undertaking perilous journeys on their own to escape persecution and hardship. They are not, and never have been, charged with any criminal wrongdoing. But they are detained, treated as criminals. They have inadequate access to medical care and outdoor recreation, they are prevented from enjoying regular contact with family members—and worst of all, there are frequent incidents of physical abuse in detention. According to a recent report by the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, “[these children] report feelings of despair, isolation and even suicide” (L.A.Times, 1/12/03). These stories are not the exception.

Child rights advocates often adopt a triumphalist tone in describing the dramatic expansion of the role of human rights since World War II. The account is familiar—the signing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, followed by the very widespread ratification of a significant corpus of international human rights conventions —on civil and political rights, economic, social and cultural rights, genocide, race discrimination, refugees and children’s rights. The UN appointments of a High Commissioner for Human Rights and of a special rapporteur to investigate child pornography, child prostitution and child sale are notable achievements, as are various humanitarian interventions. State sovereignty is not inviolable as it once was. The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) in particular is often celebrated as a special milestone, the most speedily and universally ratified human rights instrument ever, transforming children from family possessions and objects of adult protection into persons, rights bearers, active agents in their own right. (Only the U.S., among all the member states of the UN, has failed to sign or ratify this wide-ranging treaty.)

However, humanitarians, those who focus on conditions in times of war rather than peace, typically adopt a much more sober and sobering tone than their celebratory human rights counterparts. They point out that in many respects things have got worse, not better for children in the last half century. Most significant is the changing nature of modern war, with increased targeting of civilians. As UNICEF has pointed out, in the last decade alone about 2 million children have been killed, 10 million have suffered war-related trauma and 12 million have become homeless.(Unicef, The State of the World’s Children, 1996).

All wars impact heavily on children. Alongside other particularly vulnerable sections of the civilian population such as women, the disabled and the elderly, they feature disproportionately among the internally displaced and among refugee populations fleeing to neighboring states. At the same time, they are underrepresented among the population of refugees who manage to escape and seek asylum in developed states far away from the danger. Thus the overwhelming majority of child refugees are trapped close to the danger zones at home.

States—especially after 9/11—often respond to those fleeing war, persecution and civil upheaval in ways that make the situation worse. There are three negative aspects of the responses of receiving states that I would like to touch on. Each of them compounds the insecurity and trauma that children fleeing war already experience.

First, consider the legal position of children seeking asylum. Most child refugees who need asylum are accompanied by their family and are therefore included as dependents in the head of household’s asylum claim. No special legal issues arise in these cases. But, a large and growing number of separated children are forced to seek asylum on their own, unaccompanied by their families. There are about 250,000 such children in Europe and many thousands arrive in the U.S. every year. Many factors contribute to this growing problem: decimation of families by war; decisions by families to use their scarce resources to get a particularly valued member to safety; the escalation of the child smuggling and trafficking industry, and finally autonomous choices by children themselves to flee intolerable circumstances. Whatever the reasons producing their separation, these children have to apply for refugee protection in their own right and find a legal basis for getting that protection.

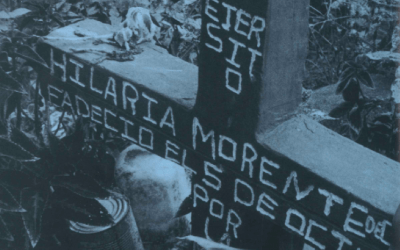

But instead of getting the preferential treatment one might expect given their particular vulnerability, these children have greater difficulty getting recognized as refugees than similarly placed adults. They have to fit their asylum claim into a legal framework developed around an adult norm. They have to persuade skeptical asylum or immigration officers that their experiences should count as a “well founded fear of persecution” within the terms of the 1951 Refugee Convention. Skepticism about children’s political activism, and their credibility and reliability as witnesses makes this hard. For example, Haitian children fleeing brutality at the hands of the Tom Tom Macoutes were considered ineligible for asylum on this basis. Child-specific forms of persecution—such as child abuse, child selling, and sexual exploitation—have not traditionally been considered valid bases for securing refugee protection. A typical case is that of Alex, an abandoned Guatemalan street child, brutally abused by his parents because he was the darkest skinned of their eight children. By 15, he had become a “resistol” glue sniffer living on the downtown streets of Guatemala City by the age of 15, and a victim of gang threats and violence for two years before he fled to Texas to seek asylum at the age of 17. The INS arrested and detained Alex and declared him “removable” as an alien without a lawful immigration status, refusing at first to recognize that he qualified for protection as a refugee. As a result of sustained NGO advocacy and pressure the U.S. adopted a set of guidelines for child asylum seekers in 1998 which, though not legally binding on decision makers and still frequently ignored by immigration courts, do at least produce a framework for a new, more generous approach.

Second, despite their obvious need for social protection, refugee children are often targets of enhanced hostility and suspicion—considered more akin to juvenile delinquents than deserving victims of human rights abuses. A senior INS juvenile coordinator I once interviewed described unaccompanied children to me as “runaways or throwaways.” This paradox is perplexing—why do particularly vulnerable children attract hostility rather than compassion? Officials often target child asylum seekers for punitive treatment, denying them access to legal advice, cajoling them with threats of detention to withdraw asylum claims and return home. According to Amnesty International, “unaccompanied children in the U.S. immigration system are routinely deprived of their rights in contravention of international and U.S. standards”. The report cites examples of perverse abuse of power: a boy placed in secure detention for 19 days for reaching over a table and tapping another boy on the head; a 14-year old girl, described as suicidal on the intake form, transferred from a shelter facility to a secure detention center because she was considered to have a “behavior problem.”

Third, refugee children find themselves subject to abuse that compounds the fear, trauma and insecurity that led to their refugee condition in the first place. For example, according to the Amnesty International report, children at a detention facility in San Antonio, Texas were punished by having their blankets and mattresses taken away, with “unbearably cold” air conditioning blasting. Children held in a secure unit in Pennsylvania were reportedly kicked, thrown to the floor, having their heads knocked into the walls for infractions such as “looking the wrong way, saying ‘can I use the bathroom’ instead of ‘may I’, or not being able to count properly.”

In the U.S.separated children who seek asylum are regularly and routinely detained, often for months on end. A third of the 5000 children detained each year are locked up in secure jails, alongside juveniles convicted of criminal offenses; they are subjected to handcuffing and shackling, and other intrusive and punitive measures (Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children, Prison Guard or Parent? INS Treatment of Unaccompanied Refugee Children (2002). Since 9/11 detention periods of children have increased and the checks and obstacles delaying release to relatives have become even more burdensome. Refugee advocates report that children seeking asylum are used as baits to find, detain and eventually deport undocumented parents already in the country.

The impossible bind of choosing prolonged detention of the child or deportation of the parent is a clear violation of the CRC mandate that the best interests of a child should be a primary consideration (maybe for good reason the U.S. has not ratified the CRC!) In spring, 2003 the U.S. military revealed that they were holding children under the age of 16 as “juvenile enemy combatants” among the 660 detainees at Camp X-Ray, the high security prison for “terrorists” at Guantanamo Bay. According to U.S. military spokespersons, at least three children between the ages of 13 and 15 had been there for months, although the exact number of children and details about them were not disclosed. Although apparently being held separately from adults, the children spent long periods in virtual isolation. Under international law ratified by the U.S., children under 15 cannot be used to participate in hostilities; compulsory recruitment cannot occur below 18 years of age. States have an international obligation to demobilize and rehabilitate child soldiers, not punish them, and to give all child detainees access to lawyers throughout legal proceedings. The revelation that children were included in the population of what Donald Rumsfeld had called “the worst of the worst,” and subjected to indefinite detention outside the reach of constitutional protection caused public outrage, which eventually led to their transfer out of Guantanamo.

Several Homeland Security-related developments specifically affect children—although not all have been negative. Surprisingly the 2002 Homeland Security Act contains some positive provisions for children seeking asylum. The act, generally known for its consolidation of 22 existing government agencies into a frighteningly Orwellian monolith, incorporates sections of the bipartisan reform-oriented Unaccompanied Alien Child Protection Act—the result of a wave of political sympathy for asylum-seeking children spawned by the Elian Gonzalez incident. The most important change is the transfer of responsibility for “unaccompanied alien children” from the INS to the Office of Refugee Resettlement, a welfare—rather than enforcement—oriented agency. This is a very positive development, an exception to the otherwise bleak environment for asylum seekers. Although the legislation does not include some critically important provisions in the Unaccompanied Alien Child Protection Act such as the obligation to appoint guardians and provide counsel, future legislation is expected torectify this. In addition, the Child Status Protection Act of 2002 improves children’s access to certain immigration benefits and protects them from “aging out” of eligibility for a wide range of benefits including protection under the (Violence against Women’s Act.

Other developments compound the problems children have faced over the past few years. Sweeping new registration requirements imposed on foreign nationals from a range of countries considered to be associated in some way with the threat of terrorism, particularly from Arab and Muslim backgrounds, have specific impacts on children. Many foreign minors, usually students, are caught by the provision that all males over 16 must register. Some have been rounded up forcibly and detained. But, much more devastating, is the impact on a hidden but far larger population of children—the thousands of American citizen children born to undocumented or out of status foreign parents. As a result of the immigration dragnet being cast over the country, these children have been forced into hiding or exile from their own country with their terrorized parents. Rather than considering the children’s citizenship a basis for securing rights for the parents (as would happen if the parents were citizens and the children needed protecting), the parents’ irregular immigration status is the basis for the effective deportation of these citizen children. We have come full circle—adult citizens have, as their most precious attribute, the fact that they cannot be deported from their country—more precious in these times, I would argue, than the right to vote or to stand for public office. But child citizens do not, in practice, have this right.

Children’s political invisibility is at the heart of this disenfranchisement. The legacy of the war and the war on terrorism is particularly hard on children. The triumphalism of child rights advocates must surely be tempered by the sobering realizations of humanitarian workers: the promise of the CRC that the best interests of children and their voices will really count in decisions that affect them is more urgent and elusive than ever!

Fall 2003, Volume III, Number 1

Jacqueline Bhabha is executive director of the University Committee on Human Rights Studies at Harvard. She is a lecturer at the Law School and an adjunct lecturer at the Kennedy School of Government. She teaches international human rights and refugee law. Before moving to the US, she was a human rights attorney in London and at the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

Related Articles

Human Rights: Editor’s Letter

During the day, I edit story after story on human rights for the Fall issue of ReVista. During the evening, I work on my biography of Irma Flaquer, a courageous Guatemalan journalist who was…

ONGs en América Latina y los derechos humanos

Las ONG ofrecen mil modos de recordar la dignidad humana a los gobiernos y las sociedades. Las dos experiencias que esbozo en esta nota reflejan algunas de las estrategias asumidas por…

Peru’s Human Rights Coordinating Committee

The human rights abuses that devastated Peru from the early 1980s to the mid 1990s are once again an issue of debate in that country with the release of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation’s…