Chinese-Mexicans: Bilingual Pictorial Symbols in Soconusco, México

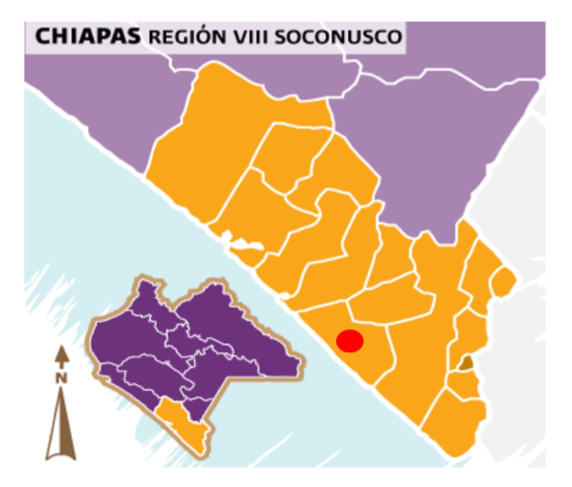

What fascinated us is the use of pictorial symbols, also called pictographs, as a form of bilingualism among the Chinese-Mexicans who live in the region of Soconusco in the southern part of Mexico, specifically in Mazatán, Chiapas, where we have conducted fieldwork since 2016 (see Map 1). The Chinese-Mexican residents mentioned the arrival of the first Chinese migrants to the region who later settled in the town of Mazatán, Chiapas. Some also settled their home in other towns such as Acocoyahua, Cacahoatán, Ciudad Hidalgo, Escuintla, Huehuetán y Huixtla (see Map 1).

In Mazatán, we find second-, third-, fourth-, and even fifth-generation descendants of the original eleven Chinese immigrants who arrived in the region. What we call “bilingual pictographs” illustrate the practices in which Chinese Cantonese is present in Spanish with a strong connotation of cultural revival and reaffirmation of their Chinese identity. Precisely, here, we’d like to note that when one talks about bilingualism, it’s usually referred to words, but our experiences with Chinese descendants in Mazatán also show us that there’s a pictographic bilingualism.

Map 1: Location of the Region of Soconusco and Mazatán, Chiapas, Mexico

Source: INAFED. http://www.inafed.gob.mx/work/enciclopedia/EMM07chiapas/municipios/07055a.html

![]() Soconusco region

Soconusco region

![]() Town of Mazatán

Town of Mazatán

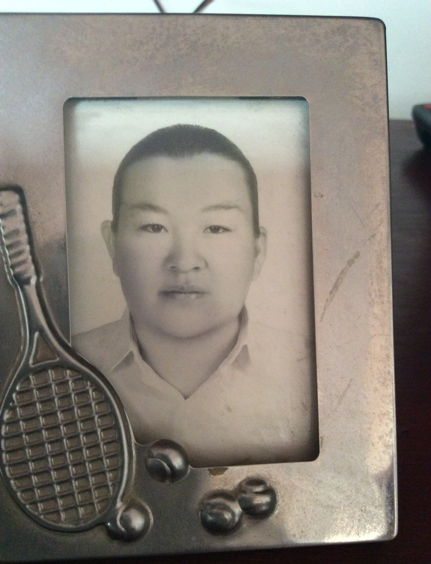

The grandfathers and great-grandfathers of the Chinese-Mexicans in Mazatán arrived to Chiapas during the 19th century, fleeing from war, epidemics and poverty. Many came illegally in merchant boats, and without a doubt their experiences were marked by forced displacement, violence, discrimination and struggled for a better life for themselves and their descendants. As Conchita Wong still remembers what her grandfather, Papá Tin (Agustín Wong) (first generation) mentioned when he arrived to the Soconusco region (see photo 1):

[…] eleven Chinese men arrived [to Mexico], they were fleeing from poverty, the misery of their land [Guangzhou] and they boarded a boat that arrived in Chiapas. The captain opened the door and said: “Get out and swim. If you survive, great, and if not, God bless you” […] so they went off swimming. Everyone [the eleven men] arrived safely to the coast. Some stayed in Tonalá, in Pijijiapan they scattered, but they still continued to look out for each other and care for each other (Interview with Conchita Wong, 2015).

Photo 1: “El Abuelo Tin” (Agustín Wong): Conchita Wong’s First Generation in Mazatán, Chiapas. Courtesy of Conchita Wong

Some members of the first generation of Chinese immigrants in Mexico started their own business with money they brought to Mexico or through their networks that included their connections with mainland China. Still others sought out loans through Mexican or Chinese lenders (for example, through a Chinese lodge) with which they could start businesses such as grocery stores, import businesses or restaurants. However, most of the Chinese immigrants worked in exploitive conditions as miners, day laborers and construction workers, particularly on the railroads. Other members of the Chinese community trafficked with undocumented immigrants, opium and jewelry, as well as other illegal products and services among China, Mexico, the United States, Latin America, Canada and the Caribbean.

Most of them faced racism and discrimination especially during the anti-Chinese movement in Mexico (first half of the 20th century). Conchita Wong’s grandfather, for example, experienced harassment, mocking and constant xenophobic commentaries, as she stated in our interviews. This antagonism demanded Chinese immigrants break their ties, to a certain extent, with their home country and assimilate themselves socially and culturally into the Mexican society. Marriages or civil unions with Mexicans increased, in order to blend themselves among the Mexican population. These measures included using their mother tongue as little as possible.

However, in Mazatán we find remnants of bilingualism that we identified as pictographic, in which Spanish and Chinese Cantonese coexist. For example, we find Cantonese sinograms—characters—painted on the façades of Chinese-Mexican homes in Mazatán. Although the descendants of Chinese immigrants do not speak Cantonese, they have managed to continue with the tradition of using the native language of their grandfathers or great-grandfathers as an identity-forming tool and of cultural revival and for linguistic practices.

For example, some of them write their Cantonese last name on the front of their houses and businesses, adding explanations in Spanish, thus identifying with the version of their last names in Spanish as well. The Chinese-Mexicans who live in Mazatán take part in cultural, identity-formation and economic activities as tokens of their ancient culture, but they also see it as an opportunity of cultural revival and identity formation. The house of Saúl Hau, another Mazatán resident, represents a good example (see photo 2). Chinese last names are very important to Chinese-Mexicans in Mazatán because they identify themselves as Chinese, in spite of the fact that at some point in the past, their last name meant discrimination and racism. Saúl explained to us the significance and relevance of returning to their Chinese cultural roots, including the use of bilingual pictographs, during the celebration of the Immaculate Conception in Mazatán on December 8.

Photo 2: The façade of Saúl Hau’s house with his last name in Cantonese. Photo by Liliana Juárez Palomino

Last names are very important to Chinese-Mexicans in Mazatán since they identify themselves as Chinese descendants, despite the fact that at some point having such a last name meant racism and discrimination. Saúl Hau, a second-generation Chinese=Mexican, inherited his parents’ restaurant business and did not have to completely rely on farm work. The living conditions of this generation improved with business ownership and higher education levels. This generation organized cultural activities about the history of Chinese migrants in Tapachula and Mazatán in the decades of the 1970s and ‘80s. Some traveled to China as children or teens and returned to Mexico speaking Cantonese. They acquired knowledge about the food, dances, customs and traditions of their ancestors. Some did not have this opportunity and were not able to speak Cantonese, but they expressed interest in their culture and wanted to learn the language of their ancestors, even if it meant through dance, the use of pictographs, and the practice of other cultural activities such as music.

An example of this cultural revival is the celebration of the dragon and lion dance devoted to the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception on December 8 in Mazatán . Some residents who are not of Chinese descent—also participate in the celebration. The community of Chinese-Mexicans organize the festivities and the promotion of the activities related to the revival of their Chinese identity, along with the use of bilingual pictographs .

Some Chinese-Mexicans from Mazatán describe their interest in learning the language of their forebears. Saúl Hau related how he and five other second-and third-generation of Chinese-Mexicans decided to take Cantonese classes at the Universidad Autónoma de Chiapas in Tapachula. He took classes for a full year but did not go back after that because of his work and family obligations. He also found it very difficult to learn, specifically speaking and writing skills. Others dropped the course much earlier. During this time, Saúl learned how to pronounce some words and simple phrases. However, Saúl’s interest in becoming bilingual rubbed off on his family and community who enjoyed going to the cultural events he organizes.

The December 8 dance is important for all the inhabitants of Soconusco, whether their heritage is Chinese or not, because the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception is the patroness of the town. The dance is also performed for the Chinese New Year and at weddings, birthdays and other Mexican celebrations as the Independence Day. Saúl Hau, who organizes the dance, teaches the dancers and designs the costumes, he is even contracted in other communities to organize dances for fiestas. During the celebration, the dancers use T-shirts with Cantonese characters together with traditional symbols such as the figures of dragons, lions and other images such as cherry blossoms. A group of young girls and women from 6 to 18 years old accompany the dance of the dragon while dancing songs in Cantonese, even though the majority of Chinese-Mexicans do not understand the lyrics at all or very well. Nevertheless, they are proud that the entire town is listening to Cantonese songs during the celebration (see Photo 3).

Photo 3: Entrance of a group of young dragon dancers at the church of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception in Mazatán, Chiapas. Photo by Liliana Juárez Palomino

Photo 4: A group of girls dancing songs sung in Cantonese during the dance of the dragon in Mazatán, Chiapas. Photo by Liliana Juárez Palomino

Photo 5: Entrance of the dragon dancers to the central plaza of Mazatán, Chiapas. Photo by Liliana Juárez Palomino

In the accompanying photos, we can see how the Cantonese characters are found both on the T-shirts and the flags. Both youth and children are immersed in this process of learning and the practice of pictographic bilingualism during the dance of the dragon and the Chinese lion. More than religious syncretism, these celebrations mark the cultural and traditional revival of what it means to be Chinese-Mexican, and above all, the bilingualism that is expressed in the streets and in the church at Mazatán. Women and girls dance to the rhythms of the songs in Cantonese and even if they don’t understand the words, they grasp the emotion and the connection to the past that is experienced in the present, recreating what it means to be Chinese-Mexican in Soconusco and a bilingualism that struggles of being reborn along with the rhythms of the dragon and the Chinese lion dance.

Related Articles

Ghosts of Sheridan Circle

Targeted killing of political enemies—assassinations—is thankfully rare in the United States. The most famous such assassination occurred in Washington, DC. And it was committed by a close ally of the United States. In September 1976, Chile’s Pinochet dictatorship…

Bilingualism: Editor’s Letter

It was snowing heavily in New York. It didn’t matter much to me. I was in sunny Santo Domingo with my New York Dominican neighbors on the Christmas break from school. I learned Spanish from them and also at the local bodega, where the shop owner insisted I ask…

Two Wixaritari Communities

English + Español

I first arrived in the wixárika (huichol) zone north of Jalisco, Mexico, in 1998. The communities didn’t have electricity then, and it was really hard to get there because the roads were simply…