Climate Change and Resource Pressures

A Photoessay By Nicoló Filippo Rosso

Protester carries a child-sized cof n made of paper in a 2016 demonstration in Bogotá’s Plaza de Bolivár protesting the deaths of Wayuu children.

Droughts in already dry places are lasting longer because of climate change and human intervention, but sometimes it’s hard to distinguish where climate change leaves off and human exploitation of natural resources begins. A case in point is La Guajira in northernmost Colombia, one of the country’s most remote and impoverished regions, home to more than 270,000 indigenous Wayuu.

There, longer droughts have meant that the streams feeding the aquifers and wells supplying water to the community got drier than usual, making any kind of meaningful farming impossible. Because of the lack of water, the region’s goat population is dwindling; the Wayuu are running out of their main source of food.

“[D]roughts can have different causes depending on the area of the world and other natural factors, [and] the majority of scientists have started to link more intense droughts to climate change,” observes the Washington D.C.-based Climate Reality Project on its website. “That’s because as more greenhouse gas emissions are released into the air, causing air temperatures to increase, more moisture evaporates from land and lakes, rivers, and other bodies of water. Warmer temperatures also increase evaporation in plant soils, which affects plant life and can reduce rainfall even more.”

The survival of the Wayuus—Colombia’s largest indigenous group—is increasingly at risk. Climate change’s effects are complicated by the fact that La Guajira is also home to one of the world’s largest open-pit coal mines, Cerrejón, a conglomerate owned by BHP Billington, Glencore and AngloAmerican. The Cerrejón coal mine broke ground in La Guajira in the 1980s and has since become the world’s tenth largest.

Cerrejón’s huge drilling operations, daily explosions and high demand of water—which taxes a desert region already suffering from droughts—have contributed to the degradation of La Guajira’s environment and the indigenous population’s way of life.

There was, however, hope for change. Initial plans for the construction of the El Cercado dam in 2011 included provisions to service nine municipalities in the department. But the pipes that should have brought water to the region were never connected to anything, as a consequence of unchecked corruption. Instead, water from the Ranchería River—the Wayuu’s main source of water—was funneled to the mine and nearby farmers.

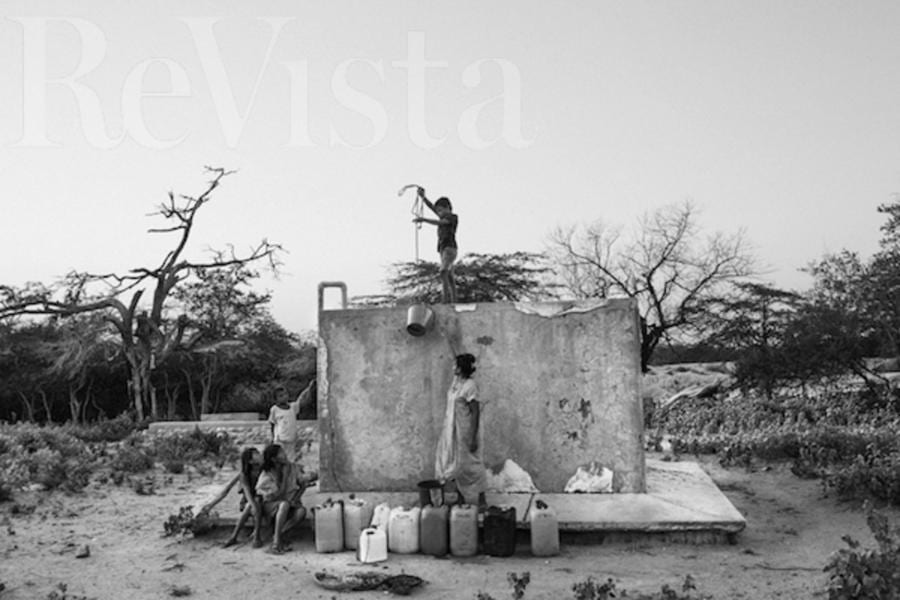

Today, the community’s sources of water are rudimentary wells often located a several hours’ walk from where the families have settled. Years of drought mean the Wayuu must dig deep to find water, and even then it is often undrinkable, causing many to fall ill. Tracking the number of Wayuu casualties is nearly impossible, as the community does not keep an official count of births or deaths. The lack of hard data makes it difficult to judge the scale of the problem and draw international attention to the humanitarian crisis. The Cerrejón mine is a deadly resource conflict that threatens the survival of the Wayuu, an indigenous people exposed to extreme poverty, thirst and environmental degradation. Telling their story can contribute to a deeper discussion about the humanitarian consequences of cheap fossil fuel and its true costs in the context of climate change.

Fall 2018, Volume XVIII, Number 1

- People fill tanks with water from a water truck. Fucai Foundation, a Bogotá-based NGO, brings water daily to more than 32 communities around the municipality of Manaure.

- Patilla Coal Pit-Cerrejon coal mine. The 330-foot deep pit allows the extraction of 400,000 tons of coal every month. Daily explosions damage the structure of neigh- boring houses, and respiratory diseases are common among local residents. Several cases have been brought against the company, which denies responsibility.

- Community members access water through a windmill built during the Rojas Pinilla dictatorship in the ’50s.

- A young girl Arijuna (not Wayuu, in Wayuunaiki) at Manaure hospital. Malnutrition and respiratory diseases affect many in La Guajira.

- At the grave of a two-year-old who died from sudden fever. Epidemics of fever have increased among Wayuu children since the rain started to fall again after four years of severe drought.

- A woman sits beside her son at Manaure Hospital. Wayuu women often walk hours through the desert to reach the closest hospital, and when they arrive, they often find that the doctors do not speak their language.

- A Wayuu woman stands in Bogotá’s Plaza de Bolivár in 2016 during a demonstration to protest the deaths of Wayuu children. She dresses in a black vest as a sign of mourning.

- A woman cooks soup in 2016. According to the Wayuu and their advocates, there is no longer enough water for the subsistence crops that once supplemented their poor diets.

- Women cook a goat at the funeral of Maricela Uriana Epiayu, 22, who died of malnutrition in August 2016. She was mother of two sons under the age of five.

- A Wayuu woman with her child at hospital of Manaure.

- A woman walks home with a tank of water. People access water from rudimentary wells with water that is often not potable.

- A bottle of Old Parr whiskey, filled with the traditional Chirrinchi brew, made from fermented sugar, lies on a tomb in a Wayuu cementery in La Guajira.

Nicoló Filippo Rosso is an Italian photographer based in Colombia.

Related Articles

Words that Matter

Those of us with little children often read The Lorax by Dr. Seuss to them at bedtime. The story points toward the past, because the Lorax is a ruin, with only residues remaining of something…

Prisoner of Pinochet: My Year in a Chilean Concentration Camp

English + Español

On September 11, 1973, at about eight o’clock in the morning, Sergio Bitar, one of Allende’s top economic advisers and the Minister of Mining, received a phone call from a colleague: the

One Long Night: A Global History of Concentration Camps

English + Español

In One Long Night: A Global History of Concentration Camps, Andrea Pitzer offers a thoughtful combination of investigative journalism and historical analysis that identifies the roots and