A Review of Dancing with the Devil in the City of God: Río de Janeiro on the Brink

A Case of Extremes

By Tamaryn Nelson

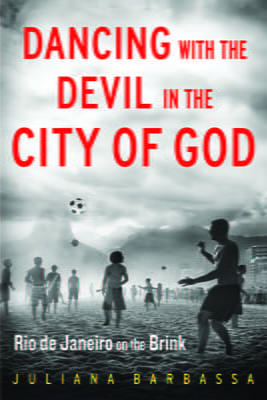

Dancing with the Devil in the City of God: Río de Janeiro on the Brink By Juliana Barbassa Simon and Schuster, 2015, 336 pages

Juliana Barbassa and I have similar stories. We are both Brazilian with a chronic case of wanderlust, but in some ways on opposite tracks: Barbassa is from Rio and I am from São Paulo, two cities known for their differences much like Los Angeles and New York. I grew up in Brazil, speaking English at home. Barbassa grew up abroad, speaking Portuguese with family. Yet after being away for almost a couple of decades, we both wanted to go home.

Five years ago, Brazil was booming and hopes were high. Economic growth was at an annual 7.5%, five times the growth of the United States, and millions left the ranks of poverty to join the middle class. Brazil had elected its first woman president and enhanced its international reputation by becoming the next host of the World Cup and the next Olympics. Overall, the country seemed to have turned the expression “Brazil is the country of the future, and always will be” on its head. This was it – the future had arrived. Thousands of Brazilians living abroad returned to Brazil, including Barbassa. Back in November 2010, she returned to Rio as the Associated Press correspondent and began rediscovering her own country while documenting the changes Rio underwent in preparation for the World Cup and the Olympics, weaving these two narratives together into Dancing with the Devil in the City of God.

Any book on Rio during the preparation of two international events could easily fall into the trap of painting an oversimplified romantic or gruesome picture of the city, known for iconic images of fun-loving football, beaches and carnival, as well as alarming violence, organized crime and pollution. Barbassa covers it all. She documents the crackdown on Rio’s sex industry and attempts to reconcile the city’s gay-friendly image with its long-standing machismo. She then goes crocodile viewing with a biologist to learn how animals native to the swamps of Barra are affected by construction on this growing high-end real estate, and visits a 60-million-ton capacity landfill that is slated to disappear for the international sports events. Through these narratives, Barbassa offers a nuanced glimpse into how Brazil was coping with being the poster-child of rapid growth and inclusivity, while still facing deep-rooted socio-economic problems. Rio served as a case study: it is a city of extremes where all facets of Brazil seem to be magnified, while the World Cup and the upcoming Olympics renewed hope that a firm external deadline and solid investment would catalyze change.

As soon as Barbassa settled in Rio, she witnessed a wave of violent hit-and-run attacks by criminal organizations that have a stronghold over much of the city and were pushing back on police efforts to reassert their presence in these areas. This led her to research the historical roots of the Red Command (Comando Vermelho), one of the most infamous criminal networks of Rio involved in arms and drug trafficking. As Barbassa finds out, during the military dictatorship in the 1970s, some of its early founders crossed paths with political prisoners. Barbassa interviews one of these inmates who tells her how they and the political prisoners shared books and food, held study groups, and collectively worked to improve prison conditions. Some of the Red Command’s earliest documents were even signed with the motto “Peace, Justice, and Liberty,” but when the political prisoners were released in August 1979 the ideals that had once fueled collective work gave way to a bloody clash in which the incipient Red Command began ruling organized crime in Rio’s prisons. Two years later, an 11-hour standoff between a Red Command bank robber and the police made it evident that the faction was better armed than law enforcement. The Red Command then grew largely unchecked, leaving the letters “CV” spray-painted in red in different areas as a reminder of its increasing stronghold in the city.

Since then little has improved for Rio’s underprivileged communities that are either often overlooked or besieged. Killings of young black males are all too common while basic infrastructure and public services are too scarce. The Olympics and the World Cup brought some hope that Rio could become a more inclusive and livable city and numerous proposals were made to improve infrastructure and address the stark inequality between favelas in the hills and the wealthy coastal neighborhoods below. However, even the government’s own Morar Carioca plan to urbanize these communities did not get off the ground. Instead, authorities opted to prioritize forced evictions and the “pacification” of these favelas.

Barbassa narrates her experience of witnessing the “pacification” of Vila Cruzeiro, which involved at least 600 police and armed forces storming the favela. Once the area was occupied, a Pacification Police Unit (Unidade de Policia Pacificadora, UPP) was set up as a permanent police presence in the favela. The other common tactic, forced evictions, has long existed in Rio but gained force and political backing with the approach of the World Cup and Olympics. Barbassa illustrates this trend through the story of Altair Guimarães, who has faced losing his home three times: in 1967 to expensive apartment complexes, in 1988 to a highway, and in 2011 to the Olympics. This time Altair learned he was about to be evicted from his home by casually watching the news, just like the rest of the city heard about the “removal.”

A common saying in Brazil is that “the more something changes, the more it stays the same” and as Barbassa’s writing progresses the reader senses a dwindling hope that Brazil’s upswing could fix some of Rio’s deepest problems. Yet while covering some of these missed opportunities, Barbassa manages to unearth special gems about the city. For example, even though Brazil boomed in the last decade and 70% of Brazilians today have cell phones, only 54% are hooked up to pipes that channel waste. Rio’s Guanabara Bay would be an idyllic setting for Olympic sailing if it were not full of trash and sewage, another problem promised to be resolved for the games. Boggled by how Rio’s water got to this point, Barbassa explores the Carioca River, which once fed the city fresh water and played an instrumental role in the establishment of Rio. Ironically, though the natives of Rio were named after it, few people today think of it at a river or even know its name—it is mostly cemented underground, and on one end it bubbles sewage into the ocean like other canals in the city. Barbassa runs by this trickle every day and decides to go upstream to trace the source in the mountains, like Darwin once did. She does this trek with Phellipe, a 28-year old man who grew up in a nearby favela and spearheaded the river’s only public clean-up effort Barbassa came across.

Five years since Barbassa arrived in Rio, many would argue that the city—much like the rest of Brazil—has gone from boom to bust. The words inflation, unemployment and impeachment have come back into our lexicon. Brazil’s economy is expected to contract by 1% in 2015 and the President’s approval ratings are at an all-time low. As for the promise of cleaning up the Guanabara Bay, Rio’s mayor announced that in August 2015 that staff would be present throughout the Olympic sailing to remove trash and waste to avoid disrupting the competition. While this may serve the purposes of the month-long Olympic games, Cariocas still will be left with 480 Olympic size swimming pools of sewage pumped into the bay every day.

Despite these challenges, changes over the last decade have made a positive imprint on deep-rooted problems that often seem intractable. If I were to critique anything missing from Dancing with the Devil in the City of God, it would be that I hoped to learn more about Barbassa’s impression of race identity in Brazil. I wish I could meet up with her to discuss this, but she just left Rio and I just landed in São Paulo, ready to begin my own journey back into Brazil.

Tamaryn Nelson is a graduate of the Harvard Kennedy School and a Jorge Paulo Lemann Fellow awarded to Brazilians working to transform the country. For the past 15 years she has led innovative research, advocacy and capacity-building on human rights across Latin America.

Related Articles

A Review of Megaprojects in Central America: Local Narratives About Development and the Good Life

What does “development” really mean when the promise of progress comes with displacement, conflict and loss of control over one’s own territory? Who defines what a better life is, and from what perspective are these definitions constructed? In Megaprojects in Central America: Local Narratives About Development and the Good Life, Katarzyna Dembicz and Ewelina Biczyńska offer a profound and necessary reflection on these questions, placing local communities that live with—and resist—the effects of megaprojects in Central America at the center of their analysis.

A Review of Authoritarian Consolidation in Times of Crisis: Venezuela under Nicolás Maduro

What happened to the exemplary democracy that characterized Venezuelan democracy from the late 1950s until the turn of the century? Once, Venezuela stood as a model of two-party competition in Latin America, devoted to civil rights and the rule of law. Even Hugo Chávez, Venezuela’s charismatic leader who arguably buried the country’s liberal democracy, sought not to destroy democracy, but to create a new “participatory” democracy, purportedly with even more citizen involvement. Yet, Nicolás Maduro, who assumed the presidency after Chávez’ death in 2013, leads a blatantly authoritarian regime, desperate to retain power.

A Review of Las Luchas por la Memoria: Contra las Violencias en México

Over the past two decades, human rights activists have created multiple sites to mark the death and disappearance of thousands in Mexico’s ongoing “war on drugs.” On January 11, 2014, I observed the creation of a major one in my hometown of Monterrey, Mexico. The date marked the third anniversary of the forced disappearance of college student Roy Rivera Hidalgo. His mother, Leticia Hidalgo, stood alongside other families of the disappeared organized as FUNDENL in a plaza close to the governor’s office. At dusk, she firmly read a collective letter that would become engraved in a plaque on site. “We have decided to take this plaza to remind the government of the urgency with which it should act.”